A Candid Conversation with Author Carey Gillam on Spotlighting Agriculture and Pesticide Disinformation, And Sometimes Paying a Price

CAREY GILLAM: DICHRON INTERVIEW

9 minute read

This Saturday, the Agriculture Media Summit kicks off a four-day gathering in Kansas City, the largest event for agriculture and livestock writers in the country. “The Agricultural Media Summit welcomes all agricultural media professionals including writers, publishers, photographers, strategic communicators, and more,” reads the summit’s website.

Well, almost all are welcome.

One writer who was invited, but then disinvited to give a talk, is Kansas City native, Carey Gillam, an award-winning book author and contributing writer for The Guardian.

After 17 years with Reuters covering agriculture and the pesticide industry, Gillam joined the non-profit U.S. Right to Know in 2016. That next year, she won the Rachel Carson Book Award from the Society of Environmental Journalists for her first book “Whitewash- The Story of a Weed Killer, Cancer and the Corruption of Science.” Last March, her second book was released: “The Monsanto Papers,” which follows the court room drama surrounding claims that Monsanto’s herbicides cause cancer.

“This is a really frightening age of disinformation, and we all have to be very careful and cautious when we are trying to discern the truth,” said Gillam, speaking to The DisInformation Chronicle from her home in Kansas City. This interview has been condensed and edited for length.

DICHRON: So what happened with you and this media ag conference?

GILLAM: One of the journalists who was organizing the speakers asked me to talk about the Freedom of Information Act. I built a career at Reuters, then at U.S. Right to Know, plus writing two books, by using documents and data obtained through Freedom of Information requests.

I have obtained documents from the EPA, Food and Drug Administration, as well as the USDA. I've sued the EPA twice, and have sued the FDA once to get access to documents. I just have a lot of experience in that area, and I sit on the Society of Environmental Journalists Task Force for Freedom of Information.

The organizer asked me to make a presentation to help other journalists understand techniques when pursuing FOIA requests. Not a very controversial topic at a media conference. But once he put my name onto the agenda, apparently some of the sponsors asked that I not be allowed to speak. He said he was embarrassed about this, felt really badly, and so I suggested that we go back to the sponsors and ask for a panel discussion, so other journalists could be involved not just me.

He then came back to me and told me the compromise was a “no-go,” and there was “huge, huge pushback.”

DICHRON: Who are the conference sponsors?

GILLAM: You can see it on the conference website and it’s some of the most well-known names in Big Ag. You have Corteva, Koch, John Deere. You have Syngenta.

Coincidentally, all this happened after I had just published a story in the Guardian on Syngenta and toxicity problems they had hidden with the pesticide paraquat.

DICHRON: I had the same thing happen to me many years ago when I was investigating financial influence in university research for the United States Senate. I was invited to give the opening talk at Tufts for a conference on conflicts of interest. Professor Sheldon Krimsky was organizing, and once the university found out I was speaking, they disinvited me.

Krimsky then resigned from the conference and the Boston Globe wrote a story about the scandal. But often, these issues are done very quietly so that no one knows.

GILLAM: We're seeing this more and more with corporate money at play in journalism conferences.

Two years ago, I wrote about Bayer seeking influence within the Foreign Press Association and the Foreign Press Foundation. I had internal documents that showed that, in exchange for very generous donations, Bayer would be involved in setting agendas for journalistic conferences and getting a say in award winners. They were going to pick what kind of stories are applauded and promoted.

DICHRON: The industry hate against you goes all the way back to when you were at Reuters. Shortly after you left Reuters, I interviewed you for Huffington Post in 2017 about this harassment. This included attacks by professor Bruce Chassy, who was running a group called Academics Review that was posting comments about what a terrible journalist you were.

It came out later in emails, that Monsanto set up Academics Review for Chassy. One of the Monsanto executives even emailed Chassy to explain this, “The key will be keeping Monsanto in the background so as not to harm the credibility of the information.”

And a couple years after I interviewed you, it came out in court documents that Monsanto targeted both of us for that interview through their intelligence “fusion center.’

GILLAM: As best we can tell from internal documents, Monsanto had an “intelligence fusion center” that monitored certain individuals and groups - almost anyone they perceived to be a threat to their agenda.

In the documents, they talk about deploying third parties, people who don’t work for Monsanto, to smear and harass anyone they see as a threat. They’ve done this to scientists and many other journalists. A key example is a front group that calls itself the American Council on Science and Health.

These groups do the dirty work so a company can appear above the fray.

DICHRON: According to the emails from their fusion center, what bugged them about my interview of you was the attention it was getting on social media, and that it had been tweeted 226 times by influencers like Michael Pollan, the Food Babe, chef Tom Colicchio, Ralph Nader, food writer Monica Eng, etc…

And then they list people who came to their defense: science writer Keith Kloor and agriculture professor Andrew Kniss.

It came out later in emails that Keith Kloor was working closely with Monsanto’s front groups and paid professors, and attended agrichemical-funded conferences. And Andrew Kniss had gotten a Monsanto grant.

GILLAM: This is about funding and deploying third-party voices in staged disinformation campaigns. These trolls do the dirty work so that Monsanto executives don’t look like they are involved.

DICHRON: One of my favorite online trolls is Stephan Neidenbach of We Love GMOs and Vaccines. He used to write for the Genetic Literacy Project and actually posted a picture of himself on social media wearing a Monsanto t-shirt.

I wrote a piece Monsanto's spying and dirty tactics, and Bayer, who bought Monsanto, wrote to me that they were no longer funding the Genetic Literacy Project, which is run by Jon Entine. What they didn’t tell me was how long they had funded the Genetic Literacy Project and for how much.

When your first book came out, you gave a talk in Cambridge where Sheldon Krimsky interviewed you. Another Genetic Literacy Project writer named Mary Mangan came up to the microphone and started babbling until someone led her out of the talk.

GILLAM: Mary Mangan is a particularly annoying troll. When my book came out, anything I would do or say … if an article came out about my book … Mary would be on social media to insult me, harass me, or make false claims. She showed up at a speaking engagement in Boston and made a fool of herself, trying to be disruptive.

The court released a document showing Monsanto’s plan devoted to smearing my book, and one of the items was to get negative reviews out. Well, Mary authored a very lengthy “book review” that ran on the website of a group called Biofortified.

In another Monsanto document, they listed Biofortified as one of their partners. So basically, this troll writes a supposed book review for a website that partners with Monsanto, and then all the other groups started tweeting it and passing it around.

That’s how the system works.

DICHRON: The American Council on Science and Health also wrote stories about Eric Lipton at the New York Times, and Stephan Neidenbach wrote about Lipton for the Genetic Literacy Project.

Why does Monsanto or any company want to pay someone like the American Council on Science and Health or the Genetic Literacy Project to say terrible things about people? Why don’t companies just do it themselves?

GILLAM: It's pretty simple. When Monsanto criticizes a journalist or a scientist, then you know that there is a certain amount of bias. And you can incorporate knowledge of that bias as you assess if you believe what you are reading. But if the same criticism comes from someone who doesn’t appear to have a vested interest, then it seems more valid.

In the internal Monsanto documents that came to light through litigation, Monsanto says over and over again how important it is to push their message out through third parties that appear to be independent of the company. And they did that because they wanted to avoid the appearance of a bias.

They made it appear as though “independent” individuals wrote articles supporting the safety of Monsanto products online, in magazines; and in scientific journals. They even deployed a team in Washington, DC to write letters to newspapers around the country that looked like they were coming from independent, unbiased individuals that had no connection to the company.

DICHRON: I want to go over three documents you sent to me. I love the names of these documents, because they could be the titles of Elmore Leonard novels.

We've got “Let Nothing Go,” “Whack a Mole,” and “Project Spruce.”

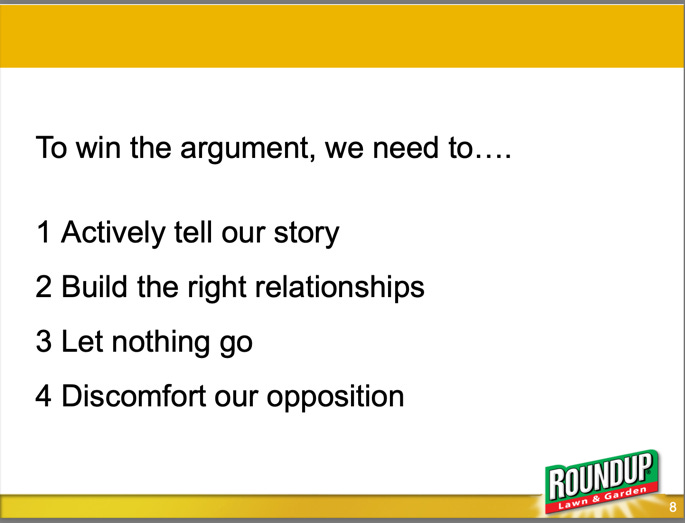

GILLAM: From the internal Monsanto documents, we know that “Let Nothing Go” was about not letting any negative word about Monsanto's products, practices or policies stand unchallenged. This could be a news story, a tweet, comment on Facebook. Anywhere that anything compromising or negative about this company might appear, they wanted someone on their team or a third party to counter it.

This is why they needed so many different players around the world to be constantly monitoring social media. This continues to happen.

DICHRON: If you go back historically, John Hill of the PR firm Hill and Knowlton, explained this same policy. In the 1950s, tobacco hired Hill & Knowlton to counteract all the negative studies showing smoking was dangerous. About 10 years later, Americans were smoking more, not less cigarettes, because of Hill & Knowlton’s campaign.

John Hill explained their success in this internal memo, “One policy that we have long followed is to let no major unwarranted attack go unanswered. And that we would make every effort to have an answer in the same day—not the next day or the next edition.”

Monsanto is just the latest example of this strategy. What was “Whack a mole”?

GILLAM: It’s whacking down anybody who is raising any questions or concerns or pointing to any potential problems with Monsanto.

Jeffrey Smith is a very prominent activist and author writing books and articles about GM foods. And Bruce Chassy, who you mentioned, was a professor at the University of Illinois. We learned after he left the university that Monsanto had provided funding for Chassy that he did not publicly disclose.

In these emails from 2010 they're talking about how to deal with Jeffrey Smith and a book Smith wrote that discusses concerns about genetically engineered foods. Chassy emails these Monsanto executives, saying “This is like playing Whack-a-mole at a carnival.” He adds that he’ll “be working on this too.”

DICHRON: And Chassy adds, “Isn't freedom of speech wonderful?”

GILLAM: Yea. This is what they were doing and they enlisted not only professors, but dieticians and nutritionists. People who have some authority and look independent, but they're out to whack down anybody who Monsanto doesn’t like.

DICHRON: And then we have “Project Spruce.”

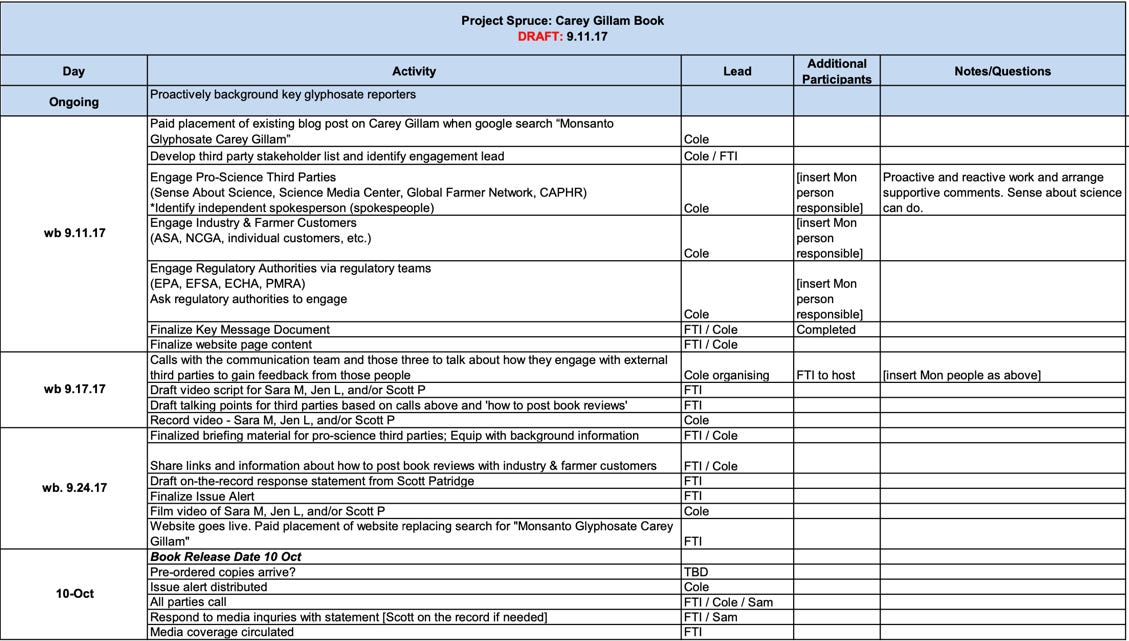

GILLAM: I knew that this had been going on, but when I saw the spreadsheet with my name on it. Well, there it was, all about how to smear and discredit my book.

Project Spruce was a code name inside Monsanto for defending its Roundup products from allegations that they cause cancer. They had a similar “project” for defending PCBs. So through Project Spruce they worked with a third party in a deep, coordinated effort to smear, discredit and try to shut down the concerns that Roundup causes cancer.

DICHRON: I love how Project Spruce activates Monsanto’s “pro science” friends. Like if you just call yourself “pro science” then it must be true. Here they list Sense About Science (who I like to say “makes no sense, isn’t about science!”) and Science Media Centre, which is just a mouthpiece for the agrichemical industry. These are supposedly prestigious groups in the U.K.

And then you see that the lead on many of these different action items is FTI Consulting, which I’ve written about for HuffPost because FTI does climate denial for the fossil fuel companies including Exxon. There’s been recent stories about FTI Consulting’s work on climate denial in the New York Times.

This is really how disinformation works as an industry—a group that does dirty work for Monsanto also does dirty work for ExxonMobil.

GILLAM: In some of the internal documents they also talk about manipulating search engine optimization on Google, so that people who might be searching for my name or my book, for instance, will get directed to negative articles that Monsanto’s third parties have posted.

That's frightening when you think about their level of sophistication and involvement.

FTI Consulting even deployed this woman to a trial posing as a journalist. She then suggested certain storylines to other reporters, and push narratives that were favorable to Monsanto, to try to influence the news reports of the real journalists.

DICHRON: If you go back to that memo from John Hill in the 1960s where he explains how they helped tobacco succeed. At the end of this section he writes, “This takes some doing. And it takes good contacts with the science writers.”

While Monsanto was working hard to knock down you and others they didn’t like, they also promoted certain writers who were their friends—Keith Kloor for instance, who kept getting invited by industry to give talks.

It also came out that Tamar Haspel, who is a food columnist for the Washington Post, was being feted to all these events by Monsanto and their allies and she was working with their PR firm, Ketchum PR.

Did you recognize how certain people in the media were being promoted as Monsanto voices?

GILLAM: Sure, it happens a lot. A lazy journalist can simply take what is handed to them—press releases and propaganda—and write stories that garner favor with big companies or important individuals. A lot of career benefits can come from cozying up to very large and powerful companies. They can feed you the stories and breaking news, and get you access to top executives that make you look good in front of your editors. That happens.

Monsanto had a very structured campaign to bring science writers into the fold and then direct what they're writing. We saw that play out with a Reuters reporter in London who received direction from Monsanto and a Monsanto consultant to write negative stories about the World Health Organization after its cancer scientists said Monsanto’s herbicide was a probable human carcinogen.

They got her to write what they asked her to write, internal Monsanto documents show. She even sent them a draft of one of her stories before it was published, which we were not allowed to do at Reuters.

DICHRON: When I saw that she had sent them the draft of her article, and marked it “confidential” I just started laughing. When you see how Monsanto orchestrated press coverage, what does that make you think about the media?

GILLAM: I am far more cynical now than I've ever been. If journalists really want to be truth tellers and shine light on facts that people don't want illuminated, they have to steer clear of these very powerful influences.

If you're a reader, you just have to take everything with a grain of salt and do your best to check, and double check, and triple check it. Go directly to the source. Look up and read research papers for yourself, and try to see if the source of information you’re relying on has some questionable connections that may bias the information. We try to lay out those connections in our work at U.S. Right to Know.

This is a really frightening age of disinformation, and we all have to be very careful and cautious when we are trying to discern the truth.