A Candid Conversation with Jared Kukura About How Corporations Twisted Wildlife Conservation to Favor Industry—Including a Classic of Science Disinformation: Tobacco

JARED KUKURA: DICHRON INTERVIEW

8 minute read

Some 10,000 bears—Asian black bears, but also sun bears and brown bears—are housed in small cages on farms across Asia. Their gall bladders are milked for bear bile, a traditional Chinese medicine. This horrific practice has been going on for decades, thanks in small part to one of the more horrific industries operating on the planet: tobacco.

American cigarette companies and bears tortured on the other side of the planet may seem a hard connection to grasp, but Jared Kukura has the evidence.

A few years back, he started exploring why wildlife conservation scientists practice “sustainable use”—a controversial program that calls for humans to exploit wildlife to protect wildlife … from human exploitation. As he started digging into the history of sustainable use, Kukura ran across the Safari Club International—a trophy-hunting organization caught promoting climate denial for the oil and gas industry—and realized that sustainable use arose out of the “wise use” movement, an antigovernment faction from the 1990s.

To understand how sustainable use became conservation biology’s version of the “safer cigarette”, we connected with Kukura at his home in San Diego, California, where he runs the Wild Things Initiative, a website that examines wildlife conservation philosophy. Scientists and writers have been making the connection between free market ideology and harmful practices by Big Tobacco, Big Oil and Big Pharma, Kukura says. “But wildlife conservation has not yet been part of that conversation.”

This interview has been condensed and edited for space and clarity.

DICHRON: When I first heard about a piece you published on this hunting organization that also did climate denial and had ties back to tobacco, I knew immediately this was Safari Club International. I had read about them years ago in the Industry Documents Library at UCSF.

But you had a lot of details I didn’t know about. And you really pulled the pants down on the “sustainable use” paradigm—this buzzword in wildlife management that I had always thought was legitimate.

KUKURA: I just stumbled into this, really. We keep hearing that the best way to save animals is to kill animals. It’s an economic argument that’s counterintuitive. To me it did not make sense.

While I was researching the conflicts of interest of researchers funded by Safari Club International, I came across a grant request package on their foundation’s website. Researchers were saying, “We’re going to use this money to promote sustainable use. We’re going to make sure that trophy hunting is viewed positively.”

And then I read more closely and found that bombshell grant request submitted by Inclusive Conservation Group.

DICHRON: How did you find those grant requests?

KUKURA: It just popped up on Google when I was searching for a researcher’s funding. Some intern must have left it up on the foundation’s website, because they don’t want that information to be public.

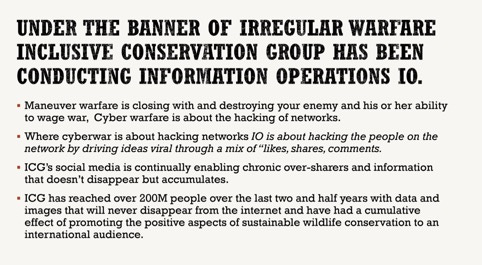

DICHRON: The grants submitted to Safari Club International all look like normal pro-hunting programs, and then you read the one by Inclusive Conservation Group …the stuff they had in their grant was mind blowing. It looked almost like a psyops campaign—intelligence warfare. Here’s how we’re going to control people’s thinking.

KUKURA: They describe military tactics and call their program irregular warfare and information operations. They even put in a quote from General Patton.

DICHRON: After you wrote about Inclusive Conservation Group, the Stanford Internet Observatory then released a report that links them back to Turning Point Action, a pro-Trump political group.

KUKURA: The Washington Post was investigating Turning Point USA for disinformation on Facebook. The Post reporter had been working with Facebook and pulling data, and they noticed connections to Inclusive Conservation Group through this marketing firm.

The Post couldn’t find anything about Inclusive Conservation Group, except what I had put on my website. So the reporter contacted me, and then Stanford got involved. Dozens of Facebook accounts were being used to promote topics, and they found a Trump troll farm.

DICHRON: Is Inclusive Conservation Group a real hunting group with ties to corporate interests, or is it just a fake front that some PR firm created? Are they involved in actual hunting?

KUKURA: All I can gather is that they are a group for the hunting and wildlife trade industry—sustainable use. If you look at the tax forms, they were born out of another nonprofit group Shikar-Safari Club International, which doesn’t have any relation to Safari Club International.

If you research Shikar-Safari Club International, you can’t find much. Every now and then they get mentioned in an article promoting hunting in North America, or for giving out awards to fish and wildlife service employees or park rangers.

DICHRON: But the core issue is whether sustainable use has any real science backing it up, which doesn’t seem to be the case. Regardless, sustainable use became a policy within International Union for Conservation (IUCN) in the 90s that they began promoting it around 2000. For people who don’t know, the IUCN is about as mainstream, button-up as you get in conservation. They’re run out of Switzerland and employ hundreds of scientists.

But you have tracked down the guy who worked with the IUCN Sustainable Use and Livelihoods group—an economist named Michael ‘t Sas-Rolfes. Well, Sas-Rolfes has ties to the Property and Environment Research Center, a free-market environmental think tank funded by corporate interests.

And one of the founding fathers of sustainable use is Steve Edwards, who comes out of the wise use movement. The wise use movement was this anti-government faction born in the Western United States in the 90s. Back in ‘95, Edwards wrote a chapter on sustainable use for a book called “The True State of the Planet” published by the Competitive Enterprise Institute, one of the more notorious climate denial groups funded by ExxonMobil.

You probably don’t know this, but the lead climate denialist at CEI is Myron Ebell, and he came out of the wise use movement.

KUKURA: That book has multiple parts: global warming is overblown, pesticides are good, don’t worry about the oceans, and sustainable use is good. In the book, they claim to shatter myths about overpopulation and other “imaginary” environmental issues.

They’re promoting the ideas as proof that capitalism and technology are going to save the world. Sustainable use popped up in the 90s with the help of anti-environmental, anti-regulation front groups for a lot of very different, terrible industries.

DICHRON: Corporate front groups promote a lot of terrible ideas beyond just sustainable use. They’ve told us smoking isn’t harmful, climate change isn’t real, fast food is healthy. But the IUCN is about as legitimate as you get. They’re the group that tells us if a species is threatened or endangered.

But they also promote sustainable use?

KUKURA: This is what scares me and why I’ve been writing about it. Think about if we had someone who was a leader for the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) or the EPA who said, “Climate change is real, but we have to keep burning fossil fuels to stimulate the economy and find solutions.”

We do hear people say that, but we label those arguments as climate denial.

And yet, the same thing is happening in conservation, and everyone’s just kind of accepted it. Because people with the IUCN, who are very well respected, have adopted this policy and promoted it for a few decades.

DICHRON: This debate on sustainable use and trophy hunting even ended up being debated in the letters section of Science. But then Science received criticism for not requiring researchers opposing wildlife import bans to disclose their financial ties.

Thus far, Science Letters had not asked authors to declare their conflicts of interests. In this case, four out of the five authors had financial links with trophy hunting groups, including the Dallas Safari Club and Safari Club International Foundation.

It’s not just front groups. It’s pretty clear there are scientists being funded by these groups to promote sustainable use, right?

KUKURA: Yeah. But if you say anything about funding, those scientists will very quickly come down on you, accuse you of defamation, and they’ll downplay money. They’ll say it’s a small amount of funding, or that they often get funding from groups that have nothing to do with trophy hunting, or that they that work with groups strictly opposed to trophy hunting.

But this was a really big deal in Science Magazine, and they had to look at changing their policies on conflicts of interest.

And people will sometimes hide this money, so it’s not a small thing. Countries like Namibia are supposed to be a role model for sustainable use. And yet a lot of the researchers who praise Namibia have these conflicts of interest, and that really flies under the radar.

Anything about conflicts of interest will get people saying, “You’re anti-science.” Or they respond, “We need money. Where else are we going to get money?”

I find that really odd, because funding is considered a big deal in pharmaceutical research and other areas of science.

DICHRON: One of the positive examples of sustainable use is the vicuña, in the South America. It’s this very cute animal that’s closely related to llamas, and it was held up as great success story in sustainable development. But now it’s gone 180 on that, right?

KUKURA: I think that’s what we see time and time again. Sustainable use activists point to the viciñua as one of their positive case studies. Their story is: the viciñua is going extinct, but the trade ban saves it. And then, when the ban’s working and populations are increasing, then they start doing sustainable use.

For a few years, it was wonderful, and local communities were getting lots of money. But then, poaching starts increasing again. And with the viciñua, you have a viciñua wool cartel that starts up.

At one point, the expert on the sustainable use program for viciñuas was all gung-ho about it, but now he’s saying it’s just possible anymore. In our globalized economy, you can’t have these little local economies and expect things to work perfectly with international pressure.

So, people have had a 180 turn, but at the IUCN, they still cite the viciñua as a success story.

DICHRON: Back in 2014, the Center for American Progress wrote a report on Safari Club International and their work for the oil and gas industry in climate denial. But you also end up talking to Stan Glantz at UCSF, who did all the work on tobacco and the tobacco documents. I first learned about Safari Club International 15 years ago when I was going through the tobacco documents, and since then I’ve ignored them.

But you went the opposite direction. You started looking at Safari Club International for their work on trophy hunting and then ended up looking through the tobacco documents.

KUKURA: This was all happenstance. As I started looking at Inclusive Conservation Group’s disinformation and climate change denial, I then noticed that climate denial groups promoted sustainable use. And from there, I read that the oil and gas industry stole disinformation tactics from tobacco.

As I was researching tobacco, Stan Glantz’s name kept popping up. I looked up his Twitter profile and noticed that anything he tweeted got this incredibly aggressive response from random accounts accusing him of anti-science. Many of the accounts looked fake and were similar to the tactics that Inclusive Conservation Group uses.

So I contacted Glantz and he was very helpful, pointing out that it’s always the same playbook. Then he told me to check out the Industry Documents Library. That’s when I found all the communications and documents from the 90s when sustainable use was being set up.

DICHRON: Did you find Safari Club International took tobacco money specifically to promote or protect smoking?

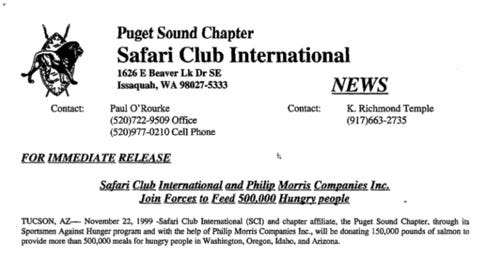

KUKURA: There was an instance of Philip Morris donating money to Safari Club International in 1999 and joining forces to feed hungry people. Philip Morris planned to generate national and local media for the project, and there ended up being a Philip Morris representative going on a radio show to complain about smoking regulations and saying, “Look at all the good work Safari Club International does feeding the needy!”

DICHRON: So Safari Club International didn’t promote tobacco, they did reputation washing, by taking donations from tobacco, to try and make tobacco look good.

KUKURA: Yes. But what I also found were people at IUCN who were coming up time and time again in different newsletters, especially with the Competitive Enterprise Institute.

There are other examples. CITES is an acronym for the group that enforces a trade agreement to protect wild animals and plants. A guy who ran CITES later ran the IWMC World Conservation Trust, a sustainable use group. And he sent a letter to the Tobacco Institute president to come to a breakfast and discuss how industries may be affected by a congressional committee hearing on CITES.

A congressman from California later faxed the invitation to the Tobacco Institute with a handwritten note saying how helpful the Tobacco Institute president was when they last met to discuss the bear bile trade.

And so it’s these little things, like thanking tobacco for helping with the bear bile trade.

DICHRON: Oh, bear bile, like what’s used in traditional Chinese medicine?

KUKURA: Yeah. People talk about the culture of traditional Chinese medicine, but they conveniently ignore that over the last 50, 60 years, it has become a huge industry. Locking bears in cages and sticking metal pipes into their gallbladders to harvest bile has nothing to do with conservation. So why were conservationists working with tobacco companies on that?

DICHRON: This has been a two-year odyssey for you. What has been your takeaway, beyond just realizing that sustainable use doesn’t make much sense and has these weird ties going back to tobacco?

KUKURA: If you look at sustainable use, or climate denial, or tobacco, what you find connecting them is that whole free market, unfettered capitalism ideology. It’s just anti-regulation, anti-government. And it doesn’t matter the industry; doesn’t matter the topic.

I’m just amazed at how these think tanks and their economists can seep into every aspect of everything around the world. It’s not just, obviously, tobacco, and oil and gas. But it’s conservation, big pharma, and agribusiness.

Some people are pointing that out. But wildlife conservation has not yet been part of that conversation.

The 1990’s is absolutely NOT where the term “wise use” originated in terms of wildlife conservation. The ideas of multiple uses and sustainable yields originated in the time of Teddy Roosevelt, John Muir and Gifford Pinchot. This was a time when National Parks and other lands were being preserved for the first time in human history. Wise Use was terminology used by the battling factions of this time to fight for reasonable management of the country’s natural resources. There’s so much known history there it should not be hard to locate. Sheesh!