ALINA CHAN: DICHRON INTERVIEW

A candid conversation with the Broad Institute’s Alina Chan, on being labeled a conspiracy theorist, realizing science writers are failing, and why we need to find out how the COVID pandemic began

8 minute read

Since the COVID outbreak early last year, experts have struggled to understand how the virus began infecting humans. While most conjecture that the pandemic resulted from a “spillover,” where a wild animal passed it to a human, others have speculated that the virus could have first infected one of the many researchers who study these viruses in labs.

Two different labs in Wuhan, China, study coronaviruses, but almost any mention of a possible lab leak is inevitably dismissed on social media and in many news accounts as a “conspiracy theory.” But some who promote the “conspiracy theory” critique have ties to labs that collect and study these viruses—a classic conflict of interest. One of the loudest critics of the lab leak theory is Peter Daszak, who runs the EcoHealth Alliance, a nonprofit research group that has had financial ties with one of the labs in Wuhan to collect and study viruses.

Months after the outbreak, Alina Chan, a molecular biologist at the Broad Institute of Harvard and MIT, began following the virus origin discussion on Twitter, attempting to knock down what she feels is misinformation. Last September, Boston Magazine featured her in a story about the possibility that the pandemic started with a lab leak in Wuhan.

“This is not what I do in my day job,” she said, when contacted by The DisInformation Chronicle. “I’m just doing this in my spare time, because I think it’s important we learn how this pandemic started.” Over several phone calls we discussed the controversy swirling around where the virus came from and how she tries to ignore being called a “conspiracy theorist” for speaking up. Here is an edited and condensed version of our talk.

DICHRON: For someone who is dying from this virus in Wisconsin, why do they care where it came from?

CHAN: If you don't know how this happened, how can you prepare for the next pandemic?

There are different mitigation strategies. If it did emerge through the wildlife trade, you have to be very aggressive in shutting down trafficking of exotic animals.

People are now sampling wild viruses, and bringing them back to labs, and studying them. Many scientists are advocating for scaling up this virus hunting to predict a possible pandemic. But if this came from such a lab, this research could be accelerating the risk for another pandemic.

Hunting for viruses and then studying them in labs has its own risks.

DICHRON: Anyone who has said that this virus came from a lab is being dismissed as a conspiracy theorist. This whole time, I’ve thought, “But why could it not have come from a lab?”

CHAN: In early 2020, Trump had come out saying that this came from a lab in Wuhan. Just from Trump saying that, I think that made a lot of people who don't like Trump assume the opposite position. I think this response is something that's very human.

DICHRON: Let me run you down an interesting timeline.

In February 2020, The Lancet published a statement that says, “We stand together to strongly condemn conspiracy theories suggesting that COVID-19 does not have a natural origin.”

Several dozen researchers signed this, including Peter Daszak of the EcoHealth Alliance, which collects and studies viruses with a Wuhan lab. Another was Jeremy Farrar, director of the Wellcome Trust (one of the largest biomedical research funders on the planet); Jim Hughes, former director of the National Center for Infectious Diseases; and Rita Colwell, former head of the National Science Foundation.

CHAN: But some of these people also have EcoHealth affiliation. Hughes is on their board, and Rita Colwell now has an EcoHealth appointment.

DICHRON: Right. This statement in The Lancet spurs an article in The Guardian, where Peter Daszak refers to the idea of a lab origin as a “crackpot theory.” Daszak repeats this in Science Magazine saying, “We’re in the midst of the social media misinformation age, and these rumors and conspiracy theories have real consequences.”

But in May, Filippa Lentzos of King’s College publishes a couple of pieces in The Bulletin of Atomic Scientists. She says we need to have a credible investigation to figure out if this is a natural event or a lab leak. Oddly enough, Lentzos studies disinformation and biolab security. She’s rarely quoted by reporters, but she’s an expert in looking at both conspiracies and lab problems.

That same month, you publish a preprint of a study that Newsweek covers in an article titled, “Scientists Shouldn't Rule Out Lab As Source of Coronavirus, New Study Says.”

And Peter Daszak dismisses you on Twitter: “This is a poorly designed phylogenetic study with too many inferences & not enough data, riding on a wave of conspiracy to drive a higher impact.”

He then dismisses you again, after you point out a paper that addresses one of his criticisms.

That next month, Daszak pens an op-ed in The Guardian about ignoring conspiracy theories that the virus could have come from a lab. There is this really strong push to label everyone a “conspiracist” if they are concerned about a lab leak.

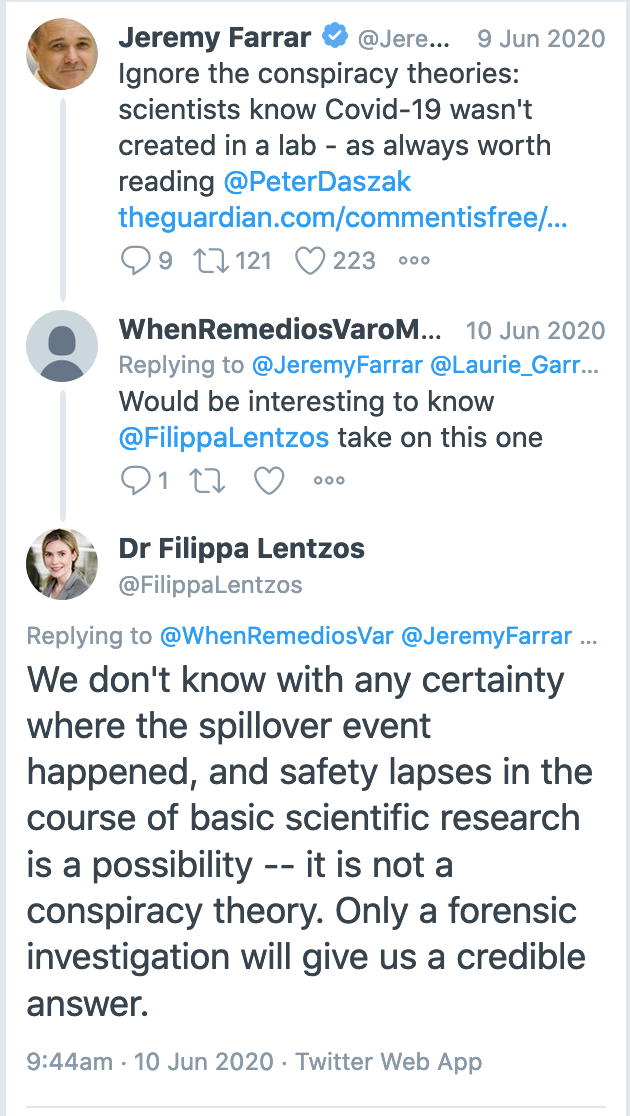

Jeremy Farrar, who signed the February Lancet statement with Daszak, tweets Daszak’s op-ed. But Lentzos responds that we don’t know if this was a natural spillover event, meaning someone got it from an animal, or if it was a lab leak. And it’s not a conspiracy theory.

Then in August, there’s an article in Nature, and Daszak again criticizes “conspiracies” that the virus could have come from the Wuhan lab. He also complains about “politically motivated organizations” that have sent freedom of information requests to get his emails.

CHAN: People are looking to see if he was orchestrating a bullshit shutdown of discussion, and intimidating scientists from talking about whether this virus could have come from a lab. It’s quite smart what he did, so early in the pandemic. It likely deterred a lot of scientists from speaking up.

DICHRON: In September, Rowan Jacobsen published a piece in Boston Magazine that discussed whether the virus could have come from a lab. He writes about you and the preprint of your study that Daszak had dismissed.

An email that later became public shows EcoHealth Alliance passing around a link to your preprint and Jacobsen’s article.

CHAN: It’s making them nervous.

DICHRON: I was surprised to see the magazine writer David Quammen on that email, about you.

CHAN: I wasn’t too surprised. David Quammen is friends with them. He follows them around, chronicling their trips. He wrote a book about following around researchers who study viruses. And I believe that he's putting together a book on COVID as well.

DICHRON: Then last November, these emails from Daszak and the EcoHealth Alliance become public from a freedom of information request. These emails show that Daszak orchestrated that statement back in February in The Lancet calling the idea of a lab leak a “conspiracy.”

While getting people to sign on to The Lancet statement, Daszak writes that the statement should “not be identifiable as coming from any one organization or person” but rather to be seen as “simply a letter from leading scientists.”

He’s moving behind the scenes to create this public outcry in The Lancet that anyone looking into a lab leak is a conspiracy theorist who is attacking scientists.

CHAN: There’s another batch of emails where Daszak wonders if he should take his name off the statement because of a conflict of interest.

DICHRON: I didn’t see those. But despite his financial ties to the Wuhan lab and seeming to manipulate the public debate behind the scenes, he gets appointed to the Lancet Covid Commission Task Force and the World Health Organization's Task Force.

CHAN: The scientific community has had issues for a long time, even predating COVID, with calling out possible misconduct, calling out conflicts of interest. For early career scientists, if you call out misconduct, you're basically setting fire to your future. [Laughs]

DICHRON: But it's so obvious something is wrong, isn't it? [Laughs]

CHAN: Yes, but to point it out can be reckless, and maybe unwise. The people who appointed him to the WHO team and the Lancet group were like, “Oh, actually, that connection is an advantage; it’s not a conflict of interest. That relationship actually helps us to get an insight to the Wuhan lab.”

I think that this is so naive. [Laughs]

DICHRON: I was just shocked that he was actually involved. It would be like the IRS starting an investigation of Trump’s taxes, and the government brings in Rudolph Giuliani, Trump’s own lawyer, as a special counsel to help the investigation.

CHAN: And then when you confront them about the conflicts of interest, they're like, “Oh, but they're such great friends. This way, Giuliani would have all the insight.”

DICHRON: Exactly.

CHAN: That may be true, but that would be self-destructive for Giuliani to incriminate his friend and client.

DICHRON: How did Rowan Jacobsen get that article out in Boston Magazine. I’m surprised it appeared.

CHAN: He faced a lot of troubles. Look at Nicholson Baker's January piece in New York magazine that talked about a lab leak hypothesis. I’m sure they got immense backlash from the scientific community. There's some outlets who will report on a possible lab leak, but there’s probably a lot of gatekeeping happening in the media.

Rowan Jacobsen wrote an earlier piece about the history of leaks and safety problems in labs, for Mother Jones. He said that one was also difficult to publish.

DICHRON: Last month, Daszak and the WHO group went to Wuhan, and then held a long press conference about the trip. Lentzos wrote this really funny piece about what was said, “WHO: COVID-19 didn’t leak from a lab. Also WHO: Maybe it did.”

What a confusing mess.

CHAN: They kept backtracking. If you watched the press conference, the team leader said a bunch of things that then had to be clarified and walked back.

DICHRON: After this press conference, Daszak then dismisses the entire US intelligence community as “wrong.” Apparently, he knows more than the CIA.

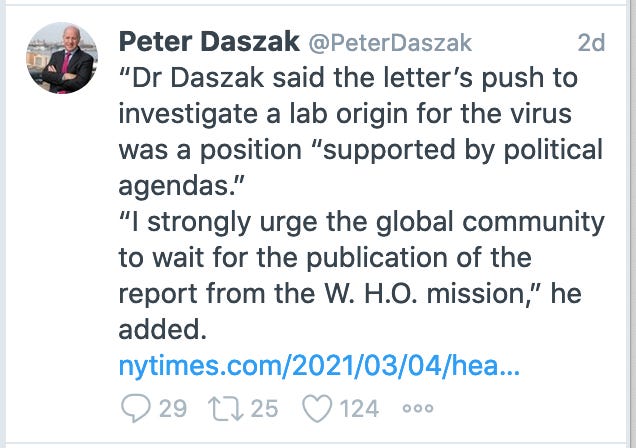

But a few days ago, you, Lentzos, and a couple dozen researchers signed a letter calling for an open and unrestricted investigation of COVID’s origin. This was covered by a few outlets, and Daszak dismissed all of you as having “political agendas.”

CHAN: What else is he supposed to do? He can’t just say, “Oh, I’ve been wrong all this time and actually a lab leak is quite plausible.” This is his only recourse.

DICHRON: Why are these people so fearful that it could have come from a lab? Who cares? We just want to know where it came from.

CHAN: If it was a leak from a lab, there’s going to be negative consequences for people who do this work, who hunt and collect viruses. It's against their interests to call for a real investigation into a lab leak.

You’re talking about something that's killed millions of people, that is going to keep on killing people. Vaccines are here, but this is not going to just disappear. If this is an accident that involved a lab, it’s the worst lab accident ever. It's very scary, right?

I would be scared to say, “I fucked up and now two million people are dead.”

DICHRON: You just got Peter Embarek of the WHO to admit that this trip to Wuhan was not a real WHO investigation. The false claim that this was a WHO investigation has been quoted incorrectly in headlines, and story after story.

CHAN: The WHO never corrected this until after they came back from the mission to Wuhan. They then admitted that if you want to investigate a lab leak hypothesis, you need a whole new mechanism. We wasted half a year negotiating for this trip.

DICHRON: I’ve noticed the media has not been covering this well.

CHAN: I think even The New York Times is having trouble bouncing back. They were so insistent that a lab leak was one of these unhinged theories. Now it’s very hard for them to backtrack, even when top scientists are speaking up.

Nature just had a podcast with some bad information.

DICHRON: It’s funny you bring up Nature, because I just saw another article they wrote and it did not even consider that the virus could have come from a lab. It reads like an editorial. And Science Magazine has had some similar unfortunate articles.

CHAN: They approached this as a conspiracy theory in early 2020. When they already had it in their mind that this must be a conspiracy theory, it gives them the overconfidence that they are actually on the side of science. And when you are so sure of the facts already, without having looked at the facts carefully . . .

And how many other times have scientists been wrong on COVID—about masks, about asymptomatic transmission? It hurts the credibility of science when experts are wrong, and refuse to admit they're wrong as quickly as possible.

DICHRON: What do you think is the possibility of us understanding where this thing actually came from?

CHAN: I think it's possible, but we're losing time. This whole WHO thing has been a massive waste. I just wish that some of these countries—not just in the West, but in Asia, in Africa—get together and set up a real investigation. We need to do that ASAP.

DICHRON: And you’re still being told on Twitter that you’re spreading conspiracy theories.

CHAN: I’m getting used to it. It still stings when it’s an actual scientist, but I just have to wait for them to come around.

Of course, I worry about my career from speaking up. But I think long term self-preservation is more important than short term issues. If another one of these viruses shows up in 20 years, I'll be in my 50s by then. Then I'll be the one who has a high chance of dying.

Many thanks Alina for pursuing the truth whatever it may turn out to be and to Dichron for publishing.

Alina Chan, I WANT WORKING WITH YOU;;;; SORRY FOR MY ENGLISH je parle le francais