Can New Software Spotlight Hidden Money Companies Pay to Doctors?

ALEX RICH: DICHRON INTERVIEW

8 minute read

Shortly before Christmas, I got an email from graduate student Alex Rich about software he was working on to tease apart data on corporate payments that influence physician behavior. “I’m approaching American healthcare the way I used to approach airplane crashes in the Air Force as an investigator and safety officer,” the former Air Force officer wrote to me last December. He then contacted me a few weeks later with a bunch of emails about Dr. Ralph Snyderman, the former Dean of the School of Medicine at Duke University.

Digging through the Open Payments database of corporate payments to doctors, Rich had caught Snyderman taking oodles of cash from Purdue Pharma. He then found that Snyderman had been named in several lawsuits aiding Purdue’s Sackler family in its efforts to drown the United States in opioids.

But Rich didn’t just catch Snyderman with his hand in the Purdue cookie jar—he got Snyderman to respond to his emails and threaten him for discussing his work with Purdue and the Sacklers. This came, I learned, after Snyderman had been avoiding questions on this same topic from reporters.

A few months later, Rich was contacted to help out backgrounding Dr. Edward Michna of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, who was testifying on behalf of opioid makers. As with Snyderman, Rich found that Michna had a ton of hidden opioid money.

Rich is now wrapping up his PhD on industry influence in medicine, but his main concern is how he can get his software in the hands of more researchers to help them spot patterns in corporate payments to physicians. He notes, with some irony, that academic doctors never hide their ties to prestigious universities, so why conceal financial affiliations to companies?

“There’s no good reason to hide large financial connections between physician authors and corporate entities,” Rich tells The DisInformation Chronicle, “no matter how great the integrity of the individual or how prestigious their institution.”

[Note to readers: We spend a great deal of time discussing the Open Payments database that lists corporate payments made to American doctors. If interested, you can learn more about Open Payments here.] This conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

THACKER: So you took all the payments to physicians on the Open Payments database and you scrape that along with the physician’s address. You can then make a map of the United States, and see when and where a company made a payment. You can see all the payments Purdue Pharma made to physicians across the United States; or you can see what time of the year this happened.

RICH: Correct. My initial efforts were to make an interactive geospatial visualization where you could watch payments drop like raindrops over time and visually recognize patterns. For example, there’s this spike in food and beverage payments at the end of December every year and this coincides with payments for speaker’s fees happening all across the country.

So you start to understand that one doctor was likely speaking to all these other doctors who got dinners and drinks that day.

I want to make it easier to explore the financial relationships between authors of articles in medical journals and industry, mostly drug and device companies.

The Open Payments database has become one of the most robust and interesting federal data sets out there. But it hasn’t met full utilization because it’s difficult to link to other datasets. It doesn’t have any of the normal things you would use to identify a physician or an author that other data sets use.

THACKER: How did you match the physicians in Open Payments with authors in publications?

RICH: Open Payments gives you the physician’s name and business address, and journal articles give you names and institutional affiliations. That’s useful in making connections between the two. If you have the PDF of a study, you can scrape the document object identifier off that first page, and then go into PubMed which gives you names, institutional affiliations, publication dates, and more.

THACKER: You came about this from experience in the military with tracking information for counter terrorism. How did you apply this training to medicine?

RICH: I’m no counter terrorism expert or intel guy, but I was a special operations pilot and worked with some counter terrorism missions. As you're trying to deal with a particular terrorist cell, you’re trying to understand their patterns—who they talk to, where they go, and when they do something. And you try to piece together where bad things are happening and how they start—their origin.

It's a little bit like a crash investigation. You want to find the earliest stage of a chain of events where you could make an intervention and prevent a bad outcome down the road.

THACKER: The point where you can step in and stop all the bad things from happening later. And you try to find this point by following the money.

RICH: Yes. If Purdue Pharma was attempting to influence tens of thousands of physicians to prescribe high doses of OxyContin that turned out to be dangerous, how did they influence those physicians? Where did they meet? Who did the speaking? Where is the information flowing?

Initially, I looked at a lot of geographic signals like venues where one physician is paid to give a talk and all these other physicians received food and beverage payments. Ultimately, I ended up looking at peer reviewed publications. When I found physicians publishing in major medical journals and not disclosing their financial conflict of interest disclosures, I really started to feel uncomfortable.

THACKER: So you ended up looking at the academic literature as the venue for companies to influence doctors. How do you scrape the financial disclosures off the studies to see if they reported that they were being paid?

RICH: I have a code to pull the conflicts of interests from the study. It's imperfect.

Critics focus on the notion that there is a corrupt quid pro quo going on with these corporate payments to doctors. I think that's rarely the case. More often there is a subconscious bias that happens when somebody has achieved expertise and prestige and thinks, “I'm a very smart person. I can't be manipulated.”

We had that in aviation. The biggest disaster in aviation history was in 1977, on an island called Tenerife. In foggy conditions, a KLM 747 ran into another fully loaded 747, on the runway. More than 500 people died. In the investigation that followed, one of the conclusions they came to was that the captain of the KLM jet repeatedly dismissed concerns from his flight crew that could have prevented the disaster. He instinctively felt that his experience and expertise meant that his copilot’s perspective couldn’t be more correct than his. That was a deadly misconception.

That was the beginning of the shift in aviation toward what we call crew resource management: the idea that the captain of the airplane is not God and needs other people to question him and to make suggestions, to bring other perspectives in so that he doesn't make a mistake. We don't seem to have that in medicine.

THACKER: The captain of the airplane is not God. When I was a Senate Investigator looking at corruption in medicine, there was a Harvard professor named Joseph Biederman, and he was being deposed in a court case—

RICH: They were going through the ranks of Harvard professors. And then they asked him what was above “professor” and he said, “God.”

THACKER: Yes. He told them in a court case, “God.” There is this God complex in medicine, and I run into it all the time. I refer to it as MD Ego—a personality disorder that falls under Narcissistic Personality Disorder. And it’s rife in academic medicine.

RICH: There are a ton of doctors who are super humble, and are there to help, and not feed their own ego. When you look at the selection process to become a senior leader in medicine—somebody who publishes a ton of studies—corporations can have a lot of influence early in someone's career and determine who gets those opportunities and is then put on stage and in front of people.

It’s a subtle process whereby these people are getting more and more comfortable with a set of corporate actors who have very strong financial incentives to see that all the decisions in the gray spaces of medicine fall in their favor.

In a clinical trial, there are a thousand decisions that fall in the gray areas, and it's in those gray areas that we can lose important elements of scientific objectivity.

THACKER: After the military, you went to Yale for graduate school and that’s where you first learned about the influence companies have on academics. You learned that Robert Alpern, the Dean of Yale’s Medical School was getting hundreds of thousands of dollars to be on the board of two companies, and was getting private flights on their corporate jets.

RICH: I saw some Connecticut outlets had reported on this, but it wasn’t anywhere on Yale’s website. You talk to people who knew this guy, and there's a corporate jet that whips in and flies him off to board meetings, kind of like a rockstar.

Straight off he goes.

But none of that was openly talked about. This was my first exposure to the payments listed at the Open Payments database. But not all the payments are there. You have to also look through the SEC filings by these companies to see if they paid these physicians even more. Dean Alpern turned out to be a board member of a giant pharma company and a giant device company, all of which was visible in their federal financial filings.

THACKER: So what have you looked at specifically—essays these physicians were publishing in medical journals or the research studies?

RICH: Daniel Kahneman is a behavioral economist who wrote “Thinking Fast and Slow.” The idea is that human thinking is broken down into two systems. System One is fast and automatic, and you're passively receiving information and reacting instinctively. System Two is slower and more contemplative, more associated with critical thinking.

Everybody works these two systems all day long because you don't have the cognitive capacities to be constantly in slow critical thinking.

Back in 2000, there were people who looked at the Vioxx trial and thought that it was weird and had problems. The vast majority of American physicians didn't catch that, didn't get a signal of something being up with that trial. My assumption is that they were in System One saying: “It's published in NEJM, by respected people. This must all be legit.”

My first study was of that trial but de-identified, so study subjects wouldn’t know they were looking at the Vioxx trial.

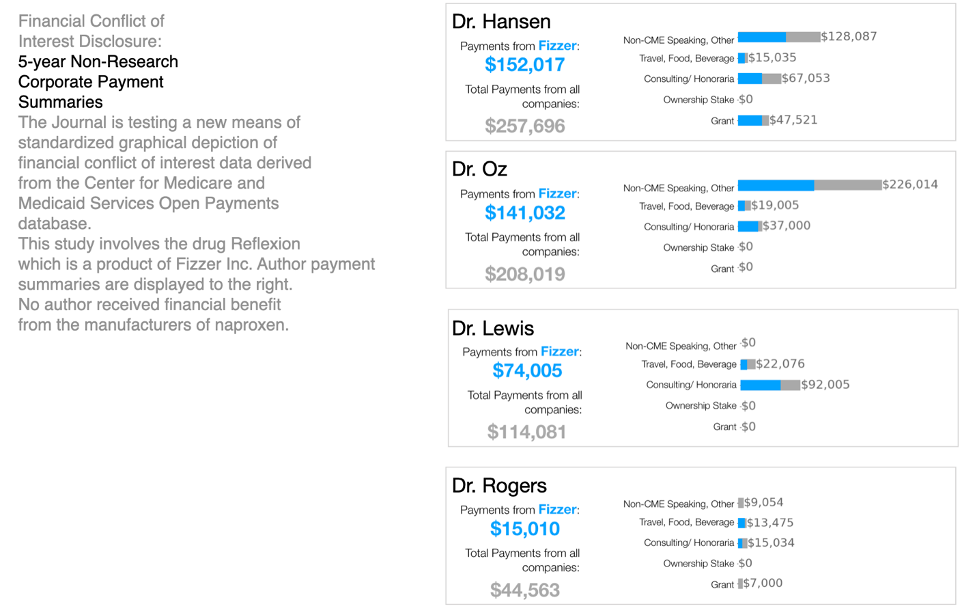

THACKER: And for the study’s disclosure, you used fake names and simulated amounts of money. But you presented that disclosure in the traditional way, where it’s hidden at the bottom of the paper, and with this new graphical format that was placed at the top of the study. Many experts have told me that financial disclosures should be right at the top of the study to alert readers.

RICH: Physicians were asked to read the study along with either a text-based traditional disclosure of the authors’ conflict of interest.

Or they were shown a graphical display of the same conflict of interest statement.

Putting this graphic in front of people, took them out of System One and put them into a System Two with critical thinking.

THACKER: So that was your initial study. And now you’re looking at all the studies being published by NEJM?

RICH: The next study was to take clinical trials that were published in JAMA and NEJM between 2015 and 2020 and run the author resolution engine code over them, matching authors to payments. I sent authors of these clinical trials graphics of their conflicts of interest and of those of their author teams. I asked them if the information was accurate and what they thought of making this type of disclosure standard. I got mixed reviews.

THACKER: Some of the information in the Open Payments federal database is not 100% accurate.

RICH: I sent the survey to all of the corresponding authors. It was actually over 120 people, but only 30 chose to be in the study. The 30 participants collectively had over $6 million in payments in the database during the disclosure windows for their articles. Over 18% of the value of those payments was not included in conflict of interest disclosures.

THACKER: What are you hoping to do with this algorithm you’ve made?

RICH: The most recent research I’ve seen that did this kind of author matching to Open Payments data was great and it got some headlines, but they did all their work manually. They found a number of $7.4 million for 118 JAMA and NEJM authors.

When I looked at just JAMA authors, I can match 3,400 authors at $320 million in payments. So I’m curious about what teams of researchers like that could do if they had access to the code I wrote, and see trends.

Fifteen percent of the JAMA authors I matched received almost 90% of the $320 million in payments.

THACKER: So there's this elite number of researchers who are gobbling up lots of money from pharma.

RICH: The more fidelity this code generates, the better it gets it. And you begin to understand trends, the ways these people's careers flow. Most of these people believe they're doing the right thing. It just so happens that the majority of the things that they say tend to benefit a multi-billion-dollar corporation.

We begin to understand that an American physician is influenced by industry, from medical school through retirement. When we put that through a microscope, are we okay with that? And if we're okay with that, fine. But it's all kind of opaque right now.

THACKER: You recently used your software to look at a physician who is testifying on behalf of the opioid industry in court cases. He loves to say he’s not influenced, but you found lots of money he had taken and not disclosed it in his published research.

RICH: I’m now going through all the Purdue money now that the company has pleaded guilty to multiple felonies; we know that this company was doing bad stuff. I'm looking through the medical journal authors that they paid, to understand how Purdue was influencing the information space around prescribers.

A lot of the time physicians didn't disclose that they were consultants for Purdue while they were writing studies and essays for journals.

THACKER: In one case, you contacted a journal about this?

RICH: Yes. This article was about the challenges with implementing opioid prescribing guidance from the CDC. Open Payments data for one of the authors, Dr. Charles Argoff, showed tens of thousands of dollars of payments from Purdue Pharma during the disclosure window for the article. Dr. Argoff’s disclosure statement didn’t mention Purdue.

I felt like readers deserve to know if an article on opioid prescribing was authored by someone who was tied to Purdue Pharma. In this case, the journal’s editors investigated the situation and the author agreed to correct the disclosure statement.

THACKER: You also helped out in a court case, about a guy named Dr. Edward Michna.

RICH: If you don’t know who somebody is working for, then you don’t know a whole lot of what that person is about to say. I was asked to do an analysis of Dr. Edward Michna, who was an expert witness for Teva in the West Virginia case. He had tens of thousands of dollars of undisclosed Purdue payments across multiple publications that he had written between 2013 and 2020.

So I started looking at the journals where he published, and Dr. Argoff stood out for Purdue payments that he wasn’t disclosing. So that journal did the right thing and they’re now correcting that.

THACKER: But you’ve not got more examples of more people not disclosing these payments.

RICH: There will be a lot of cases in which payments were not disclosed. My code has highlighted many examples involving Purdue Pharma and I’m still in the early stages of reaching out to medical journals for investigation and correction.

Systemically, we have a culture where the standards of financial disclosure are pretty messy. I don't think anybody has a clear idea of the scope and scale of industry payments flowing to medical journal authors.

I expect to open source my code soon. There should be more researchers asking questions about payments. Those conversations can enhance the transparency of the whole medical research industry and open up new lines of thinking about the problem of bias in research. We need to make sure that everyone is aware of the potential for subconscious bias that comes with being human, no matter how highly trained and experienced they might be.

Sic a team of people like Jessica Rose on this data before it's gone. Publish a secure database somewhere. Make it searchable by the public

Exposing the link between payments and suffering or death would be a litigants dream..

Very interesting interview! Certainly the more graphic form of disclosing financial conflict of authors will cause a much needed pause and more discernment when reading journal articles.