China’s Bat Lady Puts West on Alert: She’s Tired of Questions About Her Secret Military Research

Beijing officials have disappeared seven media members for reporting on COVID-19, but allow Jane Qiu access to government researchers for celebrity interview on hair?

9 minute read

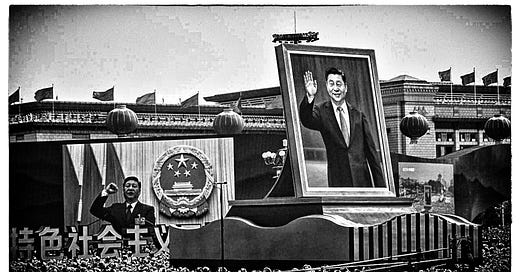

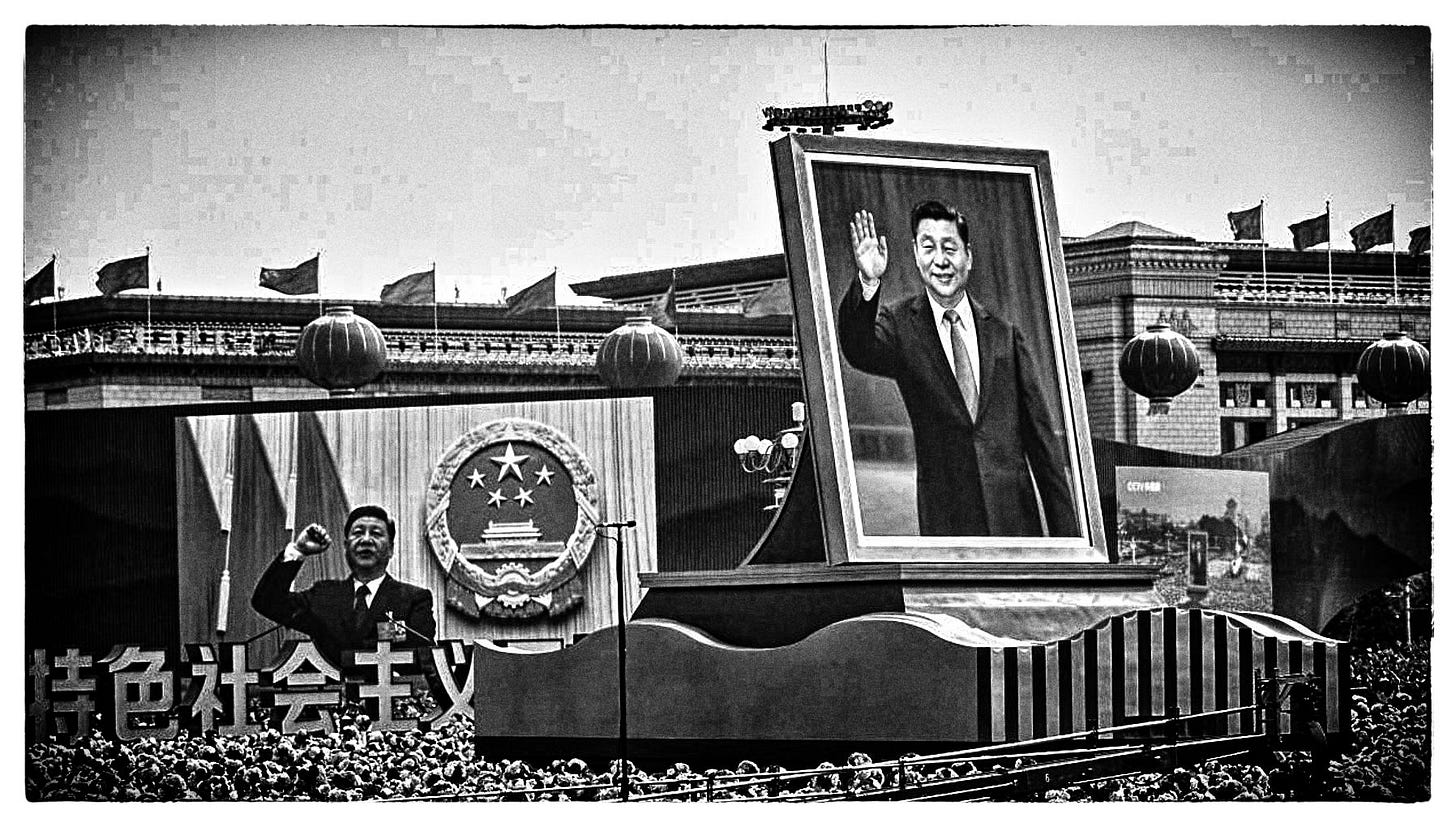

Since the COVID-19 outbreak in 2020, people around the globe have learned two things: governments are poorly prepared to handle a pandemic, and China is an autocratic state, pushing propaganda to protect the interests of its leaders. Last week, Reporters Without Borders urged the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) to release seven members of the media who were censored and remain incarcerated for reporting on the pandemic.

“Informing the public on this unprecedented health crisis is not a crime!” said an official with Reporters Without Borders (RSF). “These journalists should never have been arrested.”

In the Washington Post, columnist Sonny Bunch noted that the CCP’s bullying of the movie industry (China strangled Martin Scorsese’s 1997 film on the Dalai Lama) parallels a playbook followed by a prior authoritarian regime: Nazi Germany. Meanwhile, the New York Times reported yesterday that the CCP heavily edits scenes that depict homosexuality from the sitcom “Friends” and has disappeared cameos on the show by Lady Gaga, Justin Bieber and BTS—three entertainers who have offended the country’s leaders.

Having spent a decade covering China, journalist Melissa Chan echoed distress that contemporary China evokes Nazi Germany. “Journalists, politicians and others should consider calling elements of the Chinese state fascistic, if they are not entirely comfortable describing the state writ large as fascist,” Chan wrote in the Washington Post. “Propaganda recalls China’s glorious history while bewailing its past treatment by Western imperial powers, allowing Beijing to play both the nationalism and victim cards.”

Few deploy the Beijing victim card with more passion and wild abandon than science writer Jane Qiu. In a profile of Chinese virologist Shi Zhengli for MIT Technology Review, Qiu provides no new information about the dangerous virus research conducted at the Wuhan Institute of Virology. What Qiu does is approach her subject with soft focus lens and flattering lighting to rehabilitate the image of Shi Zhengli—a scientist at the center of international research controversy. One passage in Qiu’s profile notes:

Shi is petite, with short wavy hair that is neatly combed. Her voice is high and light, with the sparkle of a soprano (she is an amateur folksinger). That day she wore a beige sweater and blue jeans.

Many paragraphs later in this 10,000-word article, we learn more about the importance of hair when Qiu meets one of Shi’s Wuhan colleagues:

He came to pick me up at the main gate wearing a turquoise-colored T-shirt and jeans. In his mid-30s, Yang was slim and of medium height. His hair was neatly trimmed, but in a sudden breeze, his bangs danced over a forehead dominated by thick brows.

To assure the reader they are being guided by a narrator with more than just a keen eye for hair, Qiu plays up her own research experience (“I’d spent a decade working as a molecular biologist, including six years as a postdoc.”) and notes with a self-approving nod that Shi Zhengli “told me she spoke to me because my strong science background allows me to grasp the nuances and complexity of her work.”

This “group hug” on science between science writer and scientist serves as foreshadowing that readers will never learn anything that might cast a shadow on science such as specifics on Shi Zhengli’s biodefense research with the Chinese military. Instead, Qiu supplies paragraphs on a Wuhan laboratory that calls to mind a kitchen advertorial written by a chef for Martha Stewart Living:

Her lab was on the second floor of a solemn-looking cream-colored building. The main room had rows of benches with weighing machines, polystyrene ice boxes, and desktop centrifuges. Bottles of chemicals and solutions were tightly packed on the shelves. One student was typing away on a computer, while another was pipetting a tiny amount of colorless liquid from one test tube to another. The scene gave me a sense of déjà vu—I’d spent a decade working as a molecular biologist, including six years as a postdoc. It reminded me of my days in the lab.

Both NBC News and The Times of London (“Wuhan lab used Chinese military as key advisers”) have reported aspects of Shi Zhengli’s secret collaboration with the Chinese military. But despite her super exclusive access, Qiu is uninterested in exploring this most obvious, most important topic.

The reason we never learn anything about Shi Zhengli’s military research seems obvious: Jane Qiu understands that her role as science writer is to make happy talk about science, not to offend the Chinese government. When Qiu was called out for this on Twitter, she protested to the contrary, forcing reporter Keoni Everington of Taiwan News to call Qiu a liar for an “insult to our intelligence.”

Qiu alleges on Twitter that her story was fact checked, but that seems unlikely, unless this fact checking meant a cursory review of documents and links to articles provided by Qiu herself. For example, Qiu writes that the Wuhan Institute disappeared its online database of virus sequences in February 2020. However, it has long been known—see reports in the Washington Post and the Wall Street Journal—that China took down this database in September 2019.

Critics have argued that China removed the database once they detected an outbreak so that nobody could compare the viruses Wuhan researchers were studying with the COVID-19 sequence. By pretending the databases disappeared after the pandemic began and not before, CCP officials can now appear to not be hiding anything.

Other parts of Qiu’s flattering remake of Shi Zhengli just ring false. At one point Qiu writes, “ongoing studies, suggest that the pandemic probably started at the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market in central Wuhan.” But the link does not take readers to a “study” as Qiu writes; the link goes to an essay written by researcher Michael Worobey. And Qiu fails to convey to readers that Worobey corrected this essay and later admitted that the “jury is still out” on how the pandemic began.

In Qiu’s zeal to advance an argument, these details disappear like the Wuhan virus database.

Qiu also tries to distract readers from imaging that the COVID-19 virus could have originated from Shi Zhengli’s Wuhan lab by pointing to viruses closely related to COVID-19 but found in Laos. Qiu’s unspoken argument is that the pandemic could not have started in a Wuhan lab because the virus originated far, far away in Laos.

She writes, “In a preprint paper posted in September 2021, a team of Laotian and French scientists reported the discovery of viruses in Laos that, according to Robertson, shared a common ancestor with SARS-CoV-2 as recently as a decade ago.”

This is just misdirection. Last July, Wuhan researchers published a study of bat viruses and disclosed they had been collecting viruses from Laos since 2006—over 15 years ago.

Yet Qiu fails to explain that Shi Zhengli has had viruses from Laos for many, many years—viruses that are closely related to the COVID-19 virus. Much like China’s fascist government, Qiu is selling readers a tale that shaves away evidence that might let people think Shi Zhengli was studying bats viruses from Laos when an accident happened that caused the pandemic.

It’s Qiu’s collection of colorful facts—Shi Zhengli’s short wavy hair and beige sweater; her colleague’s neatly trimmed bangs and turquoise-colored T-shirt—and the studied lack of interest in critical evidence—Shi Zhengli’s military research for a fascist government—that should give readers pause for concern. Instead, we are treated to Shi Zhengli’s disapproval of us when her “girlish face suddenly dimmed” and she begins to berate those who question the Chinese government:

“I’ve now realized that the Western democracy is hypocritical, and that much of its media is driven by lies, prejudices, and politics.”

Shi paused and drew a sharp breath. Her body tensed, blood flushing her cheeks. The air swelled and seemed to grow hotter.

“They’ve lost the moral high ground as far as I’m concerned,” she said. And if politics overpowers science, “then there will be no basis for any cooperation.”

Readers do not deserve to be insulted, and editors at MIT Technology Review should demand basic attention to detail from writers. Most importantly, all of us should be alarmed that a fascist country is locking up reporters for telling inconvenient truths, while trying to fool the world with propaganda and distracting stories about hair.

At the bottom of her article, Jane Qui states that her reporting for China is supported by a grant from the Pulitzer Center and has compared people questioning the possibility of a Wuhan lab leak to Holocaust deniers. In its statement on journalists disappeared for reporting on the Covid-19 outbreak in Wuhan, Reporters Without Borders (RSF) urged the Chinese regime to release the following people:

Former lawyer-turned-journalist Zhang Zhan, 37, was sentenced to four years in prison on 28th December 2020 on the charge of “picking quarrels and provoking trouble” for reporting live from the city of Wuhan during the Covid-19 outbreak.

Political commentator Ren Zhiqiang, 69, was sentenced to 18 years in prison on 22nd September 2020 on alleged corruption charges after he highlighted the failures of the regime in their handling of the pandemic.

Political commentator Guo Quan, 52, has been detained since 31st January in the city of Nanjing on the alleged charges of “subversion of state power'' after reporting online on the Covid-19 outbreak.

Press freedom defenders Cai Wei and Chen Mei, both 27, were arrested on 19th April on the charge of “picking quarrels and provoking trouble” after they reposted censored Covid-19 news articles and are awaiting their trial, scheduled for April 2021.

Freelance journalist Chen Qiushi, 35, was forcibly quarantined on 6th February 2020 after posting videos on his blog revealing the chaos in the Wuhan hospitals and is believed to still be detained to this day.

Businessman-turned-journalist Fang Bin went missing on 9th February after reporting on hospital oversaturation in the city of Wuhan and is believed to be detained although his whereabouts have not been disclosed by the regime.

Goodness, her reporting reads like the few paragraphs that come before the steamy scenes in a romance novel. Our intrepid reporter may have been smitten by the perfect hair!

Yet, our institutions of higher learning (!) publish that.

I've always held MIT in high esteem and was appalled to read Jane's article in the technology review.

I was grateful to then read your article and since wrote to MIT to complain about the bias in their article and referenced reporters without frontiers.