Researchers Find No Evidence (Again!) Of Mask Effectiveness, Yet Self-Styled Experts Continue Promotion

Cochrane Review author says governments "don’t have the science to back up what they claim."

11 minute read

Back in the pandemic’s early days, Anthony Fauci emailed a senior health expert his honest assessment on the efficacy of masks, “Masks are really for infected people to prevent them from spreading infection to people who are not infected rather than protecting uninfected people from acquiring infection.”

Within months, however, Fauci was back on message: masks block infection, and only right-wingers believe the opposite.

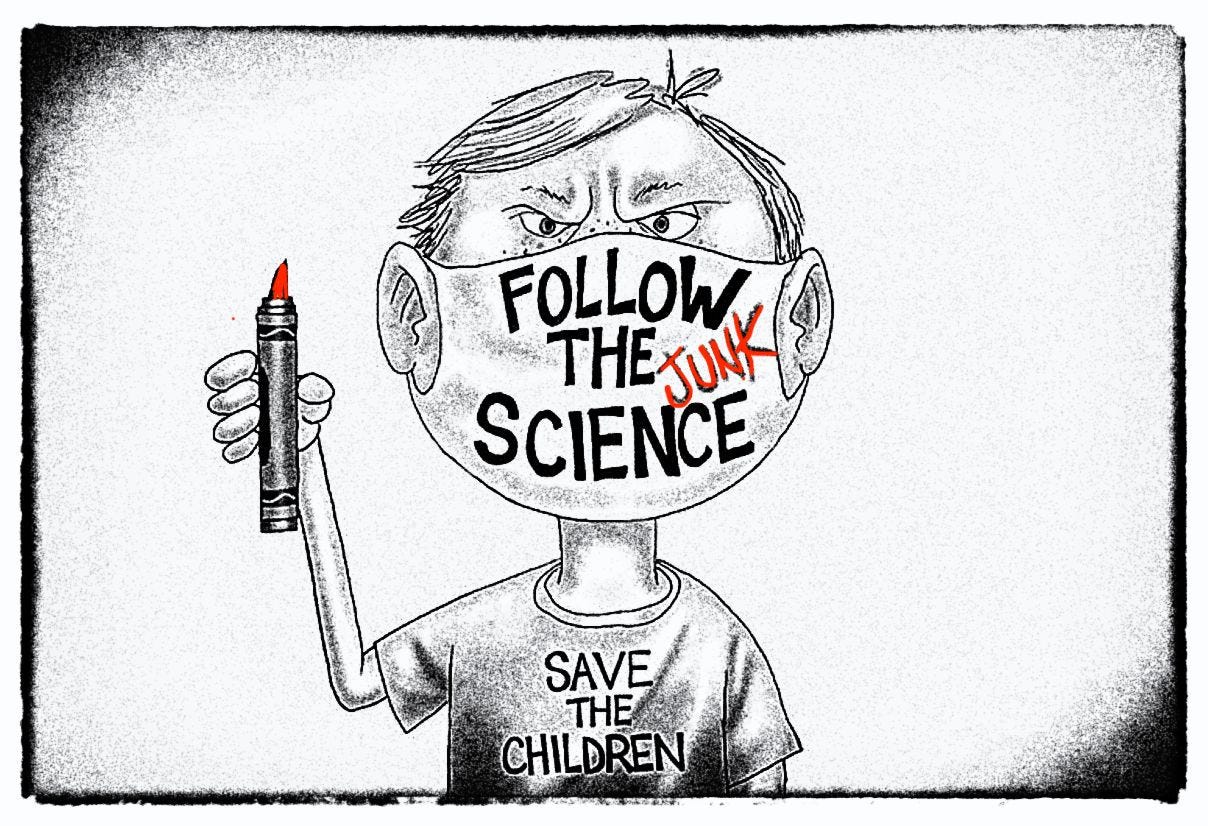

The mask controversy continues to this day, as they have become a totem of smart thinking amongst Lefty urban liberals, looking for a Team Blue war badge in America’s ongoing culture battles. Nonetheless, the science has not changed since Fauci’s first assessment that masks do little to stop virus transmission—including in the latest Cochrane Review, which examined nonpharmaceutical interventions to slow and stop virus spread.

Examining the evidence, Cochrane found no evidence that masks prevent spread of COVID, but these findings will be ignored by most media who have fallen in love with self-styled COVID experts, whose actual expertise is amplifying government policies. Even the much-ballyhooed N95 respirators were found to have no evidence backing their use

For almost a quarter century, Cochrane Reviews have represented the epitome of systematic and independent science to determine the efficacy and safety of medical treatments. So why would health experts ignore evidence-based medicine like that? To better understand their motivation, I caught up with Tom Jefferson, Senior Associate Tutor at the University of Oxford and a former researcher at the Nordic Cochrane Centre.

Jefferson has spent over three decades studying influenza and tells me that with respiratory viruses, the unexpected always happens. “But you're witnessing these organized experts now who are aggressive and censorious,” he said. “They engage in personal attacks, have all this certainty and think they can see the future.They're not scientists because uncertainty is the engine of science.”

Speaking with me from his office in Rome, Jefferson noted that more research is needed in this area, but governments cannot be trusted to fund these studies because they have already picked sides in the science.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

THACKER: What exactly is Cochrane and why should someone care what Cochrane finds?

JEFFERSON: Cochrane was founded in 1993 with the idea that we should look at what we have in the way of evidence. Why do yet another study, yet another trial? We should understand the benefits and risks of each healthcare intervention.

At the very beginning there were around 15 trials on aspirin and heart attacks, but nobody had put them together to see the benefits.

Cochrane Reviews are systematic reviews that are preceded by a protocol and they are transparent. There used to be a rule that you should update every two years, especially in certain areas, that move very, very fast. You cannot deviate from the protocol unless you have a very good reason which is recorded in the history of the review. Few if any of the observational studies I have seen on the same topic had protocols.

THACKER: What are some of the most famous or impactful Cochrane reviews—ones that changed medical care.

JEFFERSON: I can tell you the ones I did because I'm more familiar with my own work. Possibly the most famous review is the one on neuraminidase inhibitors—that's the class of antivirals, which were licensed against influenza. During the Cochrane Review update in 2009, we discovered that all the trials we'd included in previous reviews had been ghostwritten, the presentation of data were carefully selected and no one apart from the sponsors had seen the raw data, quite apart from the trials being very badly designed.

Over four years—and thanks to media pressure—the manufacturers had to provide us with the complete set of the trials. Parallel to the review, investigative journalists found that most of the World Health Organization guidelines had been written by researchers and clinicians who had ties to these manufacturers. So no wonder they were recommending the use of these drugs and stockpiling them for an influenza pandemic.

Our review finding this was quite something. My other highly cited reviews are listed here.

THACKER: This review is not about pharmaceuticals or vaccines, but physical interventions to stop the spread of influenza, coronavirus and other respiratory viruses. This area has been really interesting and very controversial, especially when it comes to masks and lockdowns.

JEFFERSON: In our review, which updates our 4 prior reviews on this same subject, the best evidence is in hand washing in children with a possible reduction of 10%.

Ten percent does not make a huge difference, but the evidence is high quality.

THACKER: Right.

JEFFERSON: The trials that were included in the review minimized bias. But the problem with interventions like handwashing in children is that the effect vanishes as soon as the teachers lose interest in supervising children to wash their hands.

What we are addressing with non-pharmaceutical interventions is actually a syndrome—a constellation of signs and symptoms such fever and cough. And they are caused by a myriad of agents. Could be viruses, could be bacteria.

In a third or up to even 80% we don’t even know if the symptoms were caused by an infection. Stress, indoor air pollution, or allergies can cause an influenza-like illness.

THACKER: The two main interventions you looked at were wearing masks and handwashing?

JEFFERSON: We looked at others, like wearing goggles or spectacles, and distancing.

THACKER: Okay.

JEFFERSON: We also looked at sending people home who were feeling unwell. That's the only randomized controlled trial on distancing that's ever been done during the influenza pandemic of 2009. People who were feeling unwell, went home from work. This seems to bring infection down in the workplace, but of course, infections went up at home.

It’s whack a mole. You squash it at one end, and it comes out the other end.

THACKER: You find a low effect for handwashing—there's a minor reduction from infection with handwashing, but with low confidence that it really works.

JEFFERSON: You need to keep up the hand washing. And, of course, we don't know whether it's direct effect on the hands or whether there’s something behavioral also that we’re missing. It’s difficult to disentangle. The underlying problem is the complexity of respiratory viral transmission which has been trivialized by false certainties.

With masks, there is really no evidence that they have any effect on these influenza-like illnesses or any specific pathogen, like the COVID virus. We take studies that are available and that fit our criteria, which are pre-specified.

Other people come to different conclusions about masks, but they have made up their own inclusion criteria, according to what they want to print. That's not science.

That is marketing or bias, whatever you want to call it.

THACKER: You say that there is a need for a large, well-designed, randomized, controlled trial that looks at these types of interventions. When the pandemic first started, I wrote exactly that for the BMJ—that we have not done any real studies on masks, so that people will stop arguing.

I thought with this pandemic going on, that the NIH or someone else, would fund a big study on masks and put this to rest.

JEFFERSON: We’ve spent countless amounts of money on masks. But we've got only three randomized controlled trials since the start of the SARS-CoV-2 story, and they're all slightly different. The setting is different, the methods are different and so on.

You expect the WHO or some big funder to fund trials to answer the question. It's very strange that hasn't happened. You can't say, “Oh, but this was an emergency, we don’t have time for a mask study.” There’s no excuse for this.

THACKER: The CDC published a study on masks their own journal, the MMWR. Reporter, David Zweig pulled it apart in The Atlantic—the CDC’s study was a mess.

But the CDC just kept promoting masks, ignoring that their own study had been torn apart. I just saw another one of these studies touting mask effectiveness. Reporters don’t even pay attention to the quality of the research, they just run with the story.

Some experts have given up on criticizing these crappy studies, because then another “Masks Are Awesome” essay just pops out.

JEFFERSON: I read this observational study, I didn’t really want to read it, but I had to, which came up with an estimate of 80% effectiveness of masks. If that were the case, SARS-CoV-2 would have likely disappeared years ago.

THACKER: Right. I mean, if masks are 80% effective how is the virus still spreading?

JEFFERSON: It would almost be at the point of eradication—very rare and sporadic. Because so much of the world has masks.

Either masks don’t work, or that they may work in specific settings when packaged with other nonpharmaceutical interventions. But this has not really been looked at in a detailed way.

The studies have to be done by independent researchers—independent of government decision making—because the government has a massive conflict of interest in finding results that align with their policies.

THACKER: I guess this is what we are seeing with these terrible MMWR studies published by the CDC that then align with CDC policies on masks. People understand conflicts of interest with pharma funding—we understand automatically that if Pfizer is funding a trial on their drug, “Whew, I better take a hard look at this data.”

But when the CDC or some government body publishes a study on masks, people don't ask those same questions. Why do you think that is?

JEFFERSON: Well, government proposed these interventions, so they’re not going to police themselves. This is just like pharma.

Some people have made fortunes and even careers out of this. And some are simply trying to dodge any kind of public criticism which might cause trouble. It’s shameful.

THACKER: This is the fifth Cochrane update on nonpharmaceutical interventions. And you now rely only on the most credible type of research: randomized controlled trials. What makes a randomized controlled trial so important that you would exclude other types of studies?

JEFFERSON: In 2020, we decided that we had such a good number of high-quality studies—randomized controlled trials—that we didn’t need to go to lower quality research, like observational studies.

Randomized controlled trials minimize bias and confounders that interfere with the analysis of the data; confounders prevent you from drawing conclusions. Randomization does that, evenly spreading confounders in two or more arms of the study. They are prospective and they follow a protocol. They are the right design if you want a credible answer.

Let me just describe you a typical observational study that we had in the previous versions of the review. This study was done three or four months after the SARS1 epidemic. The study was based on questions like, “hey two or three months ago, how many times a day did you wash your hands?”

THACKER: Right.

JEFFERSON: “Two months ago, how many times did you wear a mask?

THACKER: Right, it's going to create a recall bias in which people are going to remember that they were safer than they actually were. No one wants to admit that they did something dumb, not wash their hands.

JEFFERSON: Whatever. Human memory is what it is.

But in randomized controlled trials, you control what is going on from the beginning. You pick the population and you screen them. For instance, in COVID 19, we know that there are completely different profiles of disease and infection depending on your immune status.

If your immune status is average, then you will have a certain profile of infection, duration and secretion and so on the virus. But if you're immunedepressed or immune suppressed—the elderly, obese, anybody who's on steroids, people with autoimmune disease or those awaiting transplants depressed struggle to clear the virus.

This is why you have to pick your population and randomize them.

THACKER: You point out in the review that epidemic and pandemic viral infections pose a serious threat worldwide. Epidemics of note are SARS in 2003, MERS in 2012, SARS-CoV2 pandemic, H1N1. Even non epidemic, acute respiratory infections place a huge burden on health care system and are prominent causes of morbidity.

So if we know there's another epidemic that's going to come, and these nonpharmaceutical intervention can at least slow them down, why is all the money being poured into vaccines, vaccines, vaccines?

Vaccines only target a specific disease.

Why not study to see how much distance we need between people to slow down a virus spread? Why not study if altering air flow into classrooms, or making sure that fresh air is brought into buildings can slow infection rates?

We know it takes a long time to get a vaccine that works, but these things can work for any type of infection.

JEFFERSON: The vaccine if it works, is against a specific agent, and it is completely irrational to put all your eggs in one basket. It is rational to develop a strategy based on these nonpharmaceutical interventions, but only the ones that work.

They may make a difference—not necessarily when one is used along, but a mixture of them.

THACKER: If you had money, what studies would you want that are not vaccines or pharmaceuticals that might slow down the next epidemic? School closures or maybe looking at screening for disease?

JEFFERSON: First, I would redress the imbalance of how these issues are discussed. Advocates on some of these things have been very strident and aggressive, and they mainly focus on benefits. Very rarely do you find the study which studies the harms. We now know the lockdowns are socially and economically devastating.

This area should be reevaluated systematically. Look at lockdowns both in terms of benefits and of risks. We know that lockdowns were linked with an increase in problems like alcohol consumption, lack of exercise—

THACKER: Child abuse.

JEFFERSON: Child abuse, mental illness, alcohol abuse. Society was going to pieces at the same time as the death of some democratic principles. We had vaccine mandate coercion of health care workers.

There was all this fear—fear that the media and governments put into people. All of this should be reevaluted. But governments were behind this, have a massive conflict of interest in any research on this, and will not likely to want to go anywhere near this.

So we likely won’t go back and look at this.

THACKER: The pandemic kind of threw evidence-based medicine and Cochrane out the window. Nobody seemed to care anymore about studies unless the results showed what they wanted to believe.

Suddenly, people who liked the way Cochrane went about doing things, didn’t like Cochrane because the results didn’t favor what they wanted—masks is the most obvious here. And we see people start to change the rules, and come up with studies that could get them the right results

It’s like changing the game of football, because you don’t have good strikers, so passes also count for points, as does time of possession. Why do these people want to change the rules now. I think it’s because they can’t get the ball in the goal, so let’s pick different rules to win.

JEFFERSON: That's exactly right. And also, you are witnessing the rise of these overnight experts. I started getting involved in respiratory viruses in 1984. After having worked so long in respiratory viruses, I have two certainties: I'm going to die, and I'm going to pay taxes until that day. With respiratory viruses, the unexpected always happens.

We concluded this long ago. So you have to have a flexible response. A new type of virus might pop up and cause an epidemic

But you're witnessing these overnight experts now who are aggressive and censorious. They engage in personal attacks, have all this certainty and think they can see the future. They're not scientists because uncertainty is the engine of science.

And they don’t have the science to back up what they claim.

THACKER: After all the stress of the pandemic dies down, do you think people will come back to agreeing on the importance of evidence-based medicine and Cochrane reviews. Rigorous studies to evaluate whether a drug works or not. Or do you think things have changed, because people realize they can just change criteria to get answers they want and that will get media attention?

JEFFERSON: There’s 100 years of work on viruses, as we have chronicled in our newsletter, Trust, the Evidence.” We’ve looked at pioneers in the field and generations of researchers. But this work is gone with the rise of these overnight experts.

The WHO recently said that PCR is the gold standard for detecting if you are infectious. Anybody who works on PCR knows that's nonsense. You can detect a virus with PCR long after the infection is gone.

This is really false information, misleading information, but the media is often lapping it. I don't know whether we'll ever go back to some sensible compromise, sensible discussion. I don't know.

"Vaccines only target a specific disease. Why not study to see how much distance we need between people to slow down a virus spread? Why not study if altering air flow into classrooms, or making sure that fresh air is brought into buildings can slow infection rates?"

Why not study and recommend lifestyles that improve a population's overall metabolic and immune health? That would at least reduce the number of people vulnerable to the next pandemic. One would think that should be a major goal of public health.

Please don't mention the Dietary Guidelines, which are almost 180° wrong due to decades of regulatory capture and commercial influence.

Comment 1:

In his previous interview with Maryanne Demasi this week, Dr. Jefferson referenced this article "The sins of expertness and a proposal for redemption" from David Sackett which is a fantastic read. Anyone who missed this should check it out.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1118019/

Also want to highlight another excellent (and timely) piece from Sackett: "The Arrogance of Preventative Medicine"

https://www.cmaj.ca/content/cmaj/167/4/363.full.pdf