The New Denial Is Delay at the Breakthrough Institute (Part 2)

Ten years after jumping on the scene, contrarianism, public stumbles, and “debate-me-bro” tactics remained core to the group’s brand

This is Part Two of “The New Denial Is Delay at the Breakthrough Institute” a three-part series examining the Breakthrough Institute and ecomodernism. In Part One, we scrutinized Breakthrough’s early years, their attacks on traditional environmental groups, and their awkward defense of the oil and gas industry. To find Part One, click here.

From its 2003 beginning, the Breakthrough Institute weathered constant criticism for contrarian hot-takes on complex environmental topics. But 2014 saw two major stumbles: Breakthrough Institute Fellow Roger Pielke Jr. got bounced from Nate Silver’s 538 after writing an error-riddle column on climate change; another fiasco followed when Breakthrough invited Kieran Suckling of the Center for Biological Diversity to one of its much-ballyhooed meetings.

Having one of your senior fellows bounced from 538 after an eminent MIT scientist pointed out errors would embarrass any normal organization. But not Breakthrough. Shortly after the incident, Breakthrough’s Alex Trembath offered an odd counterargument—the climate science that contradicted Pielke Jr. actually supported Pielke Jr.

Attempting to debate facts that don’t land in their favor is boilerplate Breakthrough. More common is goading well-known experts to debate dense policy matters, because joining the stage with authorities perfumes Breakthrough with a whiff of their opponents’ expertise.

The “debate-me-bro” maneuver remains critical to polishing Breakthrough’s brand.

“In the end, they know they don’t have to win all those debates,” said Sam Bliss, a graduate student in environmental economics at the University of Vermont, who published a study in the Journal of Political Ecology examining Breakthrough. “Just getting in the debates with actual experts, and getting attention for their ideas, puts those ideas into people’s heads.”

Trembath deployed “debate-me-bro” a year back with an article that plugged plant-based processed meat. At the time, Harvard nutritionists pointed out in JAMA that many plant-based meats may not be nutritious, have high sodium levels, and make claims without independent confirmation.

But as Trembath wrote, health concern over plant meat was a “fake backlash” led by former New York Times food columnist Mark Bittman. With debate-me-bro flourish, Trembath tweeted his piece at Bittman but was ignored.

Breakthrough Institute co-founder Michael Shellenberger also relies on debate-me-bro when called out for misstatements. As catastrophic fires torched the West Coast last fall, reporters began quoting scientists who linked these fires with climate change. Nonetheless, Shellenberger hopped on Fox News to shout this science down.

When someone then tweeted that he was wrong, Shellenberger, of course, challenged that person to a debate.

Breakthrough slipped again in 2014 by inviting Kieran Suckling to their meeting. “It did not go well,” said Suckling, who founded the Center for Biological Diversity in 1989 and who the New Yorker profiled as a “trickster, philosopher, publicity hound, master strategist, and unapologetic pain in the ass."

“We got into a pissing match,” Suckling said. “Those guys cannot take a shit without denouncing environmentalists as part of their message. At this point, it’s become an obsessive-compulsive disorder.”

Other Breakthrough speakers have included Julie Kelly, the spouse of a lobbyist for the agribusiness giant ADM, who has been a contributing writer for the industry-funded Genetic Literacy Project and a freelance commentator for the National Review and Forbes. In an award-winning series on the agrichemical industry, Le Monde labeled Kelly a propagandist for Monsanto.

Also invited as a Breakthrough panelist, Washington Post food columnist Tamar Haspel has been an ardent cheerleader of GMO agriculture, and has cozy ties to Ketchum PR, the public relations firm for the agrichemical industry and the Russian oil firm Gazprom. In a quintessential piece, Haspel downplayed the dangers of the pesticide glyphosate (Round-up) after the World Health Organization’s cancer agency (called IARC) found the chemical likely caused cancer in humans.

Emails show that agrichemical lobbyists seized on Haspel’s column to attack the WHO’s IARC during a Senate Committee hearing on pesticides and agriculture.

“I formatted the Tamar Haspel piece on Round-up that ran in the Post last week as a handout in case it’s helpful,” wrote one industry lobbyist, putting together talking points to influence Senate staffers. “She does a great job of putting the IARC issue into context.”

Washington Post food and dining editor Joe Yonan did not return multiple requests for comment.

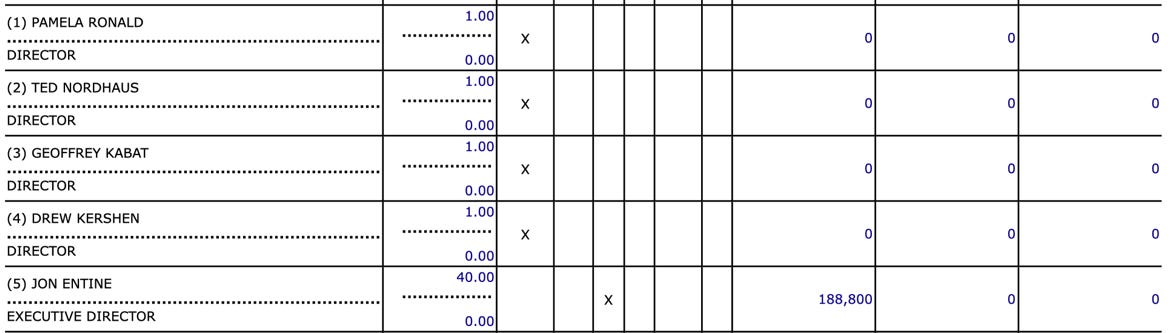

In 2015, Haspel joined Nordhaus to speak at a UC Davis event hosted by the Genetic Literacy Project, that was funded with $165,000 from the agrichemical industry. The Genetic Literacy Project is operated by former journalist Jon Entine, who claims to have never received money from corporate clients.

Nordhaus has appeared on the Genetic Literacy Project’s tax forms as a board member, and his employee Emma Kovak worked with the Genetic Literacy Project before joining Breakthrough.

When reporters at Columbia Journalism School wrote articles for the Los Angeles Times that exposed how Exxon knew years ago about climate change, Entine bylined an op-ed for the New York Post calling the investigation a “smear.” A year back, Bayer disclosed that the company “no longer provides financial support” to the Genetic Literacy Project (meaning it once did, despite Entine’s claims).

For both Shellenberger and Nordhaus, GMOs are part of the technology fix for climate. “If you don't want to turn the entire planet into a gigantic farm, you're gonna have to continue to figure out how to produce food more intensively,” Nordhaus said in a recent interview. “But obviously I think some of the GMO stuff gets oversimplified by advocates, too.”

Breakthrough also hosted a talk by Alex Berezow of the American Council on Science and Health (ACSH). Leaked documents and court records find that ACSH’s funders have included Chevron, Coca-Cola, Bayer Cropscience, McDonald’s, Monsanto, and the tobacco conglomerate Altria.

When Berezow spoke at Breakthrough, ACSH posted a photo of him at the event, amidst a gaggle of climate contrarians, including Ron Bailey of Reason, Steve Hayward of the American Enterprise Institute, and Robert Bryce of the Manhattan Institute.

Many environmental organizations chose not to comment on Breakthrough for this article, worried that even criticism gives Breakthrough publicity. But Suckling said he still engages with them on Twitter because they influence reporters attracted to contrarianism. Affiliating themselves with Breakthrough’s industry-friendly message, Suckling explained, helps reporters claim “in the middle” objectivity and protects them being labeled as “activists.”

“There are some journalists,” Suckling said, “If you ask them, ‘Are you against ISIS or are you against Nazis?’ They’ll say, ‘I’m against neither. I’m in the middle!’”

In 2015, Nordhaus and Shellenberger released “An Ecomodernist Manifesto”, a sparkly, tectonic-shifting declaration. In reality, the document rehashed arguments that, as humans sculpt the planet, the Earth has entered a new era.

Many of the 18 signatories were Breakthrough affiliates, with a smattering of professors and others who orbit Breakthrough as a means to pump up their personal brands as innovative thinkers. Two signatories bear greater scrutiny: Mark Lynas and Rachel Pritzker.

Mark Lynas is a British author and campaigner for GMO agriculture who first came to minor prominence in the mid 2000s with a book on climate change. “It was quite a prescient book at the time,” said James Wilsdon, a professor of science policy at the University of Sheffield, and the former Director of the Science Policy Centre for the Royal Society. “Mark was taking the science and giving it a richer, textured narrative so average people could understand.”

But at an Oxford farming conference in 2013, Lynas jettisoned himself from fairly obscure environment writer into international prominence when he began his talk with a confession. “I want to apologize for having spent years ripping up GM crops,” Lynas said. “I’m also sorry that I helped start the anti-GM movement back in the 90s.” With head bowed, Lynas then revealed why he had been forced to take the stage and publicly atone for past errors. “Well, the answer is fairly simple, I discovered science. And in the process—I hope—I’m becoming a better environmentalist.”

Lynas’s tale of the wayward environmentalist converted by science was too delicious for reporters to ignore, attracting coverage by the New York Times’ Andrew Revkin, the New Yorker’s Michael Specter, and stories in Slate, and The Guardian.

The Genetic Literacy Project promoted the talk, and when Fox News published a partial transcript of the confession, Lynas tweeted, “Now trending at no.2 on Fox News opinion: 'An environmentalist's confession - I was wrong about GMOs.”

Despite the staged theatrics, nothing Lynas said that day was actually new. Three years prior he had announced his conversion to GMO and nuclear supporter in New Statesman magazine. He then appeared on a Channel 4 documentary “What the Green Movement Got Wrong” where he defended GMOs and nuclear power while labeling environmentalists as “antiscience.” And in a 2011interview with Yale Environment 360, Lynas expressed disgust with environmentalists for not embracing nuclear energy and GMO agriculture, and said he had “high regard” for the work of climate contrarian Bjorn Lomborg.

But Wilsdon and other British GMO policy experts noted a much larger problem: not only was Lynas’ speech not new, it wasn’t even true. “His claim that he was one of the leaders that launched this movement isn’t true,” said Sue Mayer, who worked for Greenpeace on GMO policy during the 90s. “He may have gone on a few demonstrations, but nobody around at the time remembers him.”

Pausing at times during an interview to laugh, Wilsdon said that Lynas’s speech was baffling political theater, and noted that GMO experts and campaigners posted a letter that called out Lynas for “utter tripe.” One of the signatories is Lord Peter Melchett, a lawyer and politician who spent several years in the British government before leading Greenpeace. Another signer, Tony Juniper, now runs an agency that advises the British government on preserving and protecting the environment.

“He issued this very dramatic, but essentially, fabricated reinvention of his own biography to springboard into a new phase of his career,” Wilsdon said of Lynas. “He isn’t an expert in any of this.”

“He’s done a very impressive marketing campaign internationally,” agreed Mayer, who signed the letter calling Lynas’s claims false. “He’s not at all important in our country. But it fits into a nice story that gets lapped up by certain constituents.”

In recent years, Lynas has turned to writing for the Cornell Alliance for Science, a GMO and pesticide advocacy group at Cornell University. After the WHO’s IARC listed the pesticide glyphosate as a probable carcinogen, Monsanto and its allies began attacking the agency. The head of IARC told Politico that the agrichemical industry’s campaign reminded him of tobacco industry attacks when IARC categorized second-hand smoke as cancerous.

Lynas later published a piece at the Cornell Alliance for Science that dismissed IARC as “a little-known and rather flaky offshoot of the World Health Organization” and defended Monsanto as the victim of a “witch hunt.”

Lynas did not respond to detailed questions sent to him by e-mail.

Rachel Pritzker joined Breakthrough as the chair of its board in 2011. After co-authoring “An Ecomodernist Manifesto,” she achieved peak Breakthrough glory with two Ted Talks. In one talk, she flacked ecomodernism and recounted her transformation from little girl raised by hippies on a goat farm “where we grew our own vegetables and heated with wood” to Breakthrough-style tech modernist. After reaching this inflection point on the Ted Talk stage, Pritzker then toggled through talking points similar to what one would expect from a nuclear energy lobbyist, while also slapping down wind and solar energy.

“That’s the essential message of ecomodernism,” she said. “It’s a cause for optimism.”

Ms. Pritzker seems to have little scientific training, which makes her an odd choice to jump on stage and teach an audience about nuclear energy. According to news reports and her bio at the Pritzker Innovation Fund, Ms. Pritzker majored in Latin American studies. During the 2008 election, NPR reported that she was a “liberal nutritionist” who helped dump $1.1 million into an Ohio political action committee that opposed Senator John McCain, then running for President.

Outside of politics, Ms. Pritzker claims to have co-founded a graduate program in botanical medicine at an institution that was called the Tai Sophia Institute for the Healing Arts. She is also the daughter of Forbes top 400 member Linda Pritzker, an heir to the Hyatt Hotels fortune who has run a Buddhist center in Montana.

Besides chairing the board of the Breakthrough Institute, Ms. Pritzker has also supported several groups that collaborate with Breakthrough to promote nuclear energy and GMO agriculture, including Third Way and the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF).

This ends Part Two of “The New Denial Is Delay at the Breakthrough Institute,” a three part series examining the Breakthrough Institute and ecomodernism. To continue with Part Three, click here.

While Shellenberger may have a "debate-me-bro" attitude, he does not actually like to be debated. I came prepared to a panel I was on with him at a Berkeley Uncharted conference in 2013 and I did not let him get away with his BS. He was not happy at all and stormed out of the conference after the panel ended.