A Continued Candid Conversation with Richard Ebright on the History of U.S. Research Funding for Biological Agents in America and Abroad that Lack Critical Safety Overview

RICHARD EBRIGHT: DICHRON INTERVIEW (PART 2)

8 minute read

For most of 2020 and into the early part of this year, a group of researchers led by Peter Daszak of EcoHealth Alliance succeeded in labeling anyone who asked if the pandemic had started from a lab accident as a “conspiracy theorist.” But Daszak’s conspiracy to denigrate people as conspiracy theorists has now fallen apart.

Last week, the Washington Post reported that World Health Organization (WHO) expert Peter Ben Embarek, who led the WHO mission to Wuhan, China, to investigate the origins of the pandemic, now says Chinese colleagues influenced the WHO’s findings. Based on Embarek’s statements, the Wall Street Journal reported that closer scrutiny is needed of a lab run by Wuhan Center for Disease Control and Prevention. In response, Chinese authorities say the virus couldn’t have come from a Wuhan lab, and have run a propaganda campaign pointing to other countries as the pandemic’s origin.

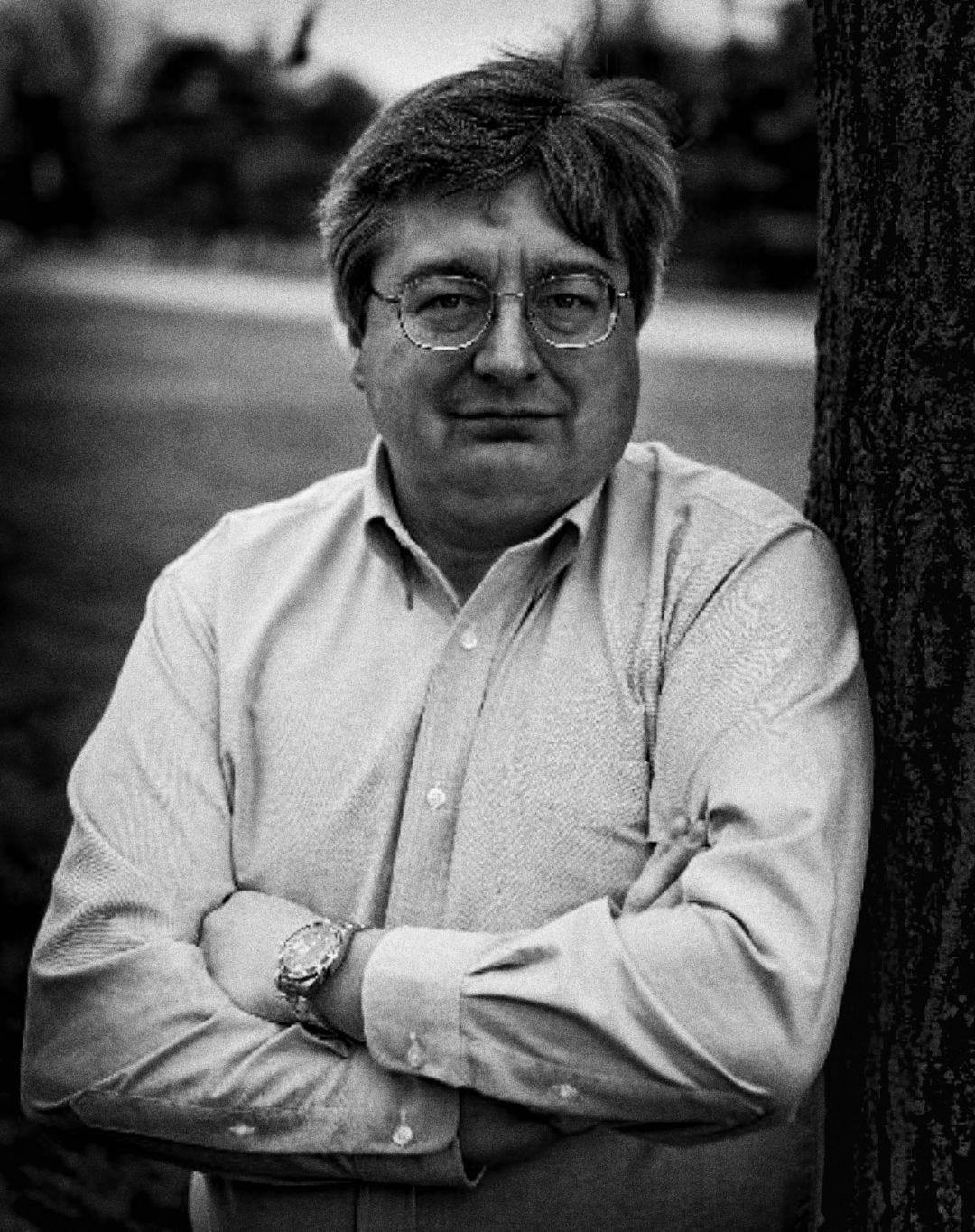

In a previous interview, Richard Ebright of Rutgers University detailed the year-long campaign by a coterie of scientists and their allies in the science-writing community to dismiss the possibility that a lab leak in China may have started the pandemic. This week, Ebright explains the two-decade history of funding and lack of safety efforts in pandemic studies and a figure central to blocking oversight of this research—Anthony Fauci, who runs the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

“Responsibility for assessing biosafety and biosecurity needs to be taken out of the hands of the federal agencies that perform and fund research,” Ebright tells The DisInformation Chronicle. “We do this with nuclear safety, through the Nuclear Regulatory Commission. We don't have the Department of Energy, which funds nuclear research, determining rules for nuclear safety.”

Here is an edited and condensed version of our talk.

DICHRON: Nature Magazine’s Amy Maxmen has tried desperately to downplay the dangers of virus research, to the point of writing stories that inaccurately state research has never led to an epidemic. What has really happened?

EBRIGHT: There have been previous large outbreaks that started from laboratories. The 1977 influenza pandemic started from a laboratory freezer in southern USSR or northern China.

In 1979, a large anthrax outbreak resulted from an accident at a biodefense laboratory in Sverdlovsk, in the U.S.S.R.

In the fall and winter of 2019, at the same time that SARS-CoV-2 was emerging in Wuhan, an outbreak of brucellosis that ultimately caused more than 10,000 human infections resulted from an accident at a vaccine laboratory in Lanzhou, China.

DICHRON: The accident at Sverdlovsk is the one that Nature’s Amy Maxmen denies, despite Nature itself having previously written about this same lab accident. Nature refuses to correct their error.

We've had numerous outbreaks start in China and the first thing that China always does is deny that it's happening. This happened in the 2002-2003 coronavirus outbreak, the avian flu outbreak in 2013, and with COVID-19. It's almost like you can predict that China is going to lie and cover up.

EBRIGHT: The original SARS outbreak in 2002-2003 was an example of natural spillover. It was not a laboratory accident, and it occurred at a time before China was performing large-scale virus research.

DICHRON: So when was the earliest high-risk or gain-of-function experiments with viruses?

EBRIGHT: That would have been 2005, 2006 and the reconstruction of the 1918 pandemic influenza virus.

DICHRON: Where was that done?

EBRIGHT: At Mount Sinai in New York, and at the CDC in Atlanta.

DICHRON: And they reconstructed a deadly virus that was gone?

EBRIGHT: Yes. This was a virus that had not been present on the planet for decades, and that, when it had been last present, had infected at least two thirds of the global population and killed at least one percent of those infected.

That got lots of coverage, with a big splash in the world media, and with pushback from Congress for having been undertaken without having performed a prior risk-benefit assessment.

But the story begins earlier. In 2001.

DICHRON: That was 9/11?

EBRIGHT: In 2001, we had 9/11 and the anthrax mailings. By November of 2001, Congress had moved to make very large appropriations for defense against biological terrorism.

DICHRON: We also started scaling up the number of these labs that work on these dangerous pathogens—the BSL-4, or biosafety level-4 labs.

EBRIGHT: We ended up with a factor-of-20 to a factor-of-40 increase in the biodefense research in the U.S. Vice President Cheney believed that the United States needed to expand research on biological weapons agents.

The Department of Defense had strict systems in place to ensure compliance with the Biological Weapons Convention. Those restrictions limited its freedom to undertake new research programs, particularly those referred to as “the leading edge of biodefense.” This meant potential offensive as well as potential defensive relevance.

Cheney’s response was to transfer this research from the Department of Defense to the National Institutes of Health, specifically to the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID). By about 2004, this transfer was complete, and NIAID had been transformed into an arm of the defense sector.

This made the NIAID Director Anthony Fauci a major player.

DICHRON: What happened then?

EBRIGHT: In 2003-2004, the National Academies of Sciences (NAS) established a committee that reviewed biomedical “dual use research of concern.” This is defined as biomedical research that has both health and military implications.

The NAS committee identified seven research activities—“seven deadly sins”—that posed high risk. The seven deadly sins were activities that render a vaccine or drug therapy ineffective, or that increased a pathogen's virulence, transmissibility, or range of hosts. These five correspond to gain-of-function. The final two are evasion of diagnostics or detection, and then weaponization. These are more directly military oriented.

Although the NAS committee originally focused on controlling information about high-risk research, scientists and science policy specialists later agreed that information about high-risk research posed much less of a threat than the actual products of the high-risk research. Enhanced, more dangerous pathogens from this research could trigger a pandemic, if released deliberately or accidentally.

By 2004-2005, the term “dual use research of concern” began to be superseded by “gain-of-function research of concern.” The main threat was not information with dual-use, but the enhanced pathogen with its gain-of-function.

DICHRON: OK.

EBRIGHT: And right around that time, it's announced that the 1918 pandemic influenza virus had been reconstructed.

DICHRON: Whatever happened to that virus? Did they destroy it afterwards?

EBRIGHT: No. On the contrary, it has been distributed for research worldwide.

DICHRON: So then we have 2011. That’s when Ron Fouchier and Yoshihiro Kawaoka announce they can make this crazy dangerous, airborne version of avian influenza.

EBRIGHT: Avian influenza virus H5N1 very rarely infects humans. But, when it does, it kills more than half.

With funding from NIAID, Fouchier in the Netherlands and Kawaoka in Wisconsin showed that they could start with H5N1, and obtain an enhanced version of H5N1 that freely transmitted by respiratory droplets in mammals. They did this with serial passage in ferrets, basically selective breeding of the virus.

The virus they created, were it deliberately or accidentally released, would have high pandemic potential. This got major attention and major pushback, both from the Congress and from the White House.

DICHRON: This would be the Obama administration.

EBRIGHT: Yes. Policy makers insisted on an explanation why NIAID had funded this work, and, especially, why NIAID had funded this work without performing a prior risk-benefit assessment.

DICHRON: This is a great time to do virus research. It’s like being an oilfield wildcatter before the Department of the Interior and EPA are created. You just go out, start drilling … here’s my oil well.

In this case, Fauci just funded whatever kind of research he wanted. Nobody to say no.

EBRIGHT: Basically, the question to the NIAID Director, Anthony Fauci, and the NIH Director, Francis Collins was: “How could you again have funded high-risk research without performing a risk-benefit assessment, particularly after we went through this same discussion five years ago with 1918 pandemic influenza virus?”

Another source of outrage was that NIAID had funded this high-risk not only in the U.S., but also overseas. Fouchier was based at a university in the Netherlands. But Fauci and Collins insisted the research was critical for US security, penning an op-ed in the Washington Post titled, “A Flu Virus Risk Worth Taking.”

Fauci then orchestrated a short moratorium on similar work with influenza viruses. After Congress and the White House turned their attention elsewhere, Fauci and Collins lifted the moratorium and expanded funding for gain-of-function research.

DICHRON: But they implemented a review process for this research.

EBRIGHT: No. That’s much later. After the moratorium, more funding was made available for this research, and the funding continued to be approved without risk-benefit assessment.

DICHRON: So what triggered the Cambridge Working Group to form in July of 2014, because this is first organized effort against this type of research.

EBRIGHT: In 2014, there was a major anthrax accident at the CDC in Georgia, and a major anthrax accident at a Department of Defense facility in Utah. Then, vials containing smallpox virus were found in a leaking box in an unsecured storage room at an FDA and NIH facility in Maryland.

That’s three biosafety and biosecurity breaches, at three national labs.

The National Science Advisory Board for Biosecurity (NSABB) had been established to advise the U.S. government on biosafety and biosecurity, but had not met in more than a year. Well, they expressed an interest in addressing these three incidents and the still-unresolved issue of gain-of-function research.

The NIH, in response, dismissed most members of the NSABB and selected newer, more malleable members. This came to be known as the “Saturday Night Massacre at the NSABB.”

Angered by their dismissal, and NIH lack of interest in biosafety and gain-of-function research, the dismissed NSABB members joined with others to found an independent task force.

This was called the Cambridge Working Group.

DICHRON: So that’s what started it.

EBRIGHT: The accidents at national labs and the founding of the Cambridge Working Group captured the attention of the Obama White House. By October of 2014, Obama’s Office of Science Technology Policy (OSTP) announced a “pause” on federal funding for gain-of-function research.

Federal agencies were asked to inventory their current and proposed research projects. If they were reasonably anticipated to increase transmissibility or pathogenicity of influenza, SARS, or MERS viruses, then they were to “pause” those projects and proposals.

The “pause” enabled time to develop a process that would assess risk-benefit for this category of work.

Eighteen projects initially were identified and sent cease-and-desist letters, but seven were exempted two months later. NIH Director Collins certified these were urgently necessary for U.S. public health.

DICHRON: What happened next.

EBRIGHT: In December 2017, under Trump, the “pause” was lifted and was replaced by the Potential Pandemic Pathogen and Care and Oversight Framework, which is called P3CO. P3CO calls for risk-benefit assessment of high-risk pathogens research.

This means research that increases the pathogenicity and/or the transmissibility of a potential pandemic pathogen. Under P3CO, agencies must identify such research proposals and forward them to be assessed at the Cabinet or Secretary level.

Well, the agencies have nullified the P3CO framework by just not identifying research proposals that meet the criteria.

In the 3 1/2 years that the P3CO Framework has been in effect, only three out of several dozen research proposals that meet the criteria have been forwarded for risk-benefit assessment.

DICHRON: Has anyone from the Cambridge Working Group been invited to be a part of this review process?

EBRIGHT: No.

DICHRON: So we now have a system in place, but the system is essentially ignored?

EBRIGHT: Correct. NIAID Director Fauci and NIH Director Collins realized that, by failing to identify and forward proposals for review, they effectively nullify the policy.

DICHRON: This includes the funding to Peter Daszak’s EcoHealth Alliance for the project that Trump shut down.

EBRIGHT: Correct. That project met the criteria for the “pause” and also met the criteria to be reviewed under P3CO. But it was not paused, and it was never reviewed.

DICHRON: Are there other problems with P3CO?

EBRIGHT: There is no transparency in the review process. The names of members of the review committee, their affiliations, the proceedings, and the committee’s decisions all are secret.

DICHRON: So we finally have a safety process in place, but it's secretive. We don't know who's doing it and we don't know what they're doing.

EBRIGHT: Yes. But that isn't the worst problem. The worst problem is that the reviews are not even occurring, for the simple reason that the funding agencies, through negligence or misfeasance, are not identifying and forwarding proposals for review.

DICHRON: What do you think needs to happen?

EBRIGHT: Responsibility for assessing biosafety and biosecurity needs to be taken out of the hands of the federal agencies that perform and fund research. It then needs to be assigned to an independent federal entity.

We do this with nuclear safety, through the Nuclear Regulatory Commission. We don't have the Department of Energy, which funds nuclear research, determining rules for nuclear safety.

This ends part two of our candid conversation with Richard Ebright on pandemic research and politics. In part one, Ebright discussed the coterie of scientists and allied reporters who sought to bury the idea that the pandemic could have started with a lab accident in Wuhan, China. To read part one, click here.

Hmm. The evidence for zoonotic spillover is as thin for SARS as it is for SARSv2.