COVID Patient Zero Will Never Be Known

Pandemic likely started before Wuhan scientists got sick, according to multiple lines of evidence, including a censored study several Chinese scientists were too scared to put their names on.

12 minute read

Leaks over the last couple weeks provide clearer evidence that dangerous virus research at the Wuhan Institute of Virology (WIV) caused the pandemic. But despite several claims, this evidence does not prove Wuhan researcher Ben Hu was patient zero—the first person to become sick with the virus.

Claims that Wuhan’s Ben Hu was patient zero were first made in a joint report by Public and Racket followed by much more skeptical reporting in the Wall Street Journal, which confirmed Ben Hu’s name while noting that Hu was “one of the researchers who became ill in November 2019 with symptoms that American officials said were consistent with either Covid-19 or a seasonal illness.”

Pushing the pandemic’s beginning to November 2019 calls into question the validity of studies published in Science Magazine, which argued the pandemic began in a market a month later in December 2019. Unsurprisingly, Science published a report on Friday trying to throw cold water on the latest news, with quotes from Chinese scientists disputing the latest evidence that they became sick in November 2019 and engaged in dangerous virus research. The value of statements from Chinese scientists remains dubious as the Chinese Communist Party, to this day, falsely claims that only 5,200 people in China have died of COVID. Plus, the article was authored by writer Jon Cohen, who was previously caught betraying a whistleblower to virologists who dispute the possibility of a lab accident. (Treason of the Science Journals).

Several lines of evidence point to the virus circulating even before the Wuhan researchers became sick in November 2019, meaning there may have been several leaks of the virus, or researchers may have caught the virus while it was spreading in Wuhan and tracked it back into the lab.

In an interview with me last September, former CDC Director Robert Redfield walked through the evidence of how the pandemic began, but in a halting fashion, catching himself at several points to make sure he did not disclose classified information.

This virus, I knew right away… I had other information over the next couple of weeks that wasn't public. Now, a lot of it has been declassified. The COVID epidemic obviously didn't start in December; it actually started way back in August, or maybe September in Wuhan.

Redfield discussed some of that unclassified material in a June 2022 Wall Street Journal essay. “Saying that this pandemic started in November,” he told me recently. “I think people are getting a little out in front of their skis.”

Other lines of evidence included a preprint published in February 2020 based on information provided to Chinese researchers living in the States. That study was censored by a preprint site and several journals that refused to publish it. The study involved five researchers who examined evidence sent surreptitiously from China. Three of these reseachers still wish to remain anonymous to protect friends and family the Chinese Community Party.

“We figured out it must have started between late September and the middle of October,” says Lucia Dunn, Professor Emeritus of Economics at Ohio State University. Dunn’s study was ignored until the Washington Post mentioned it briefly last January. “We were just trying to get out accurate numbers to the medical community. It's very disturbing to feel like your medical establishment is not trustworthy anymore.”

This interview with Dunn has been condensed and edited for brevity and clarity.

THACKER: Your study didn’t get any play in the media until just this last January, when it was briefly mentioned in a Washington Post piece reporting on China’s coverup of COVID deaths. To this day, China claims only 5,200 people have died of COVID in China.

Yet, three years ago, you caught China hiding their true numbers of deaths.

DUNN: This is a really unusual story. In the Post article, my co-author was called Mai He, which is his name, but he goes by Mike. Mike’s a research physician at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis.

Mike, I, and some other people were contacted by a Chinese doctor who had gotten information about what was happening in Wuhan. This is at the end of January 2020. And this Chinese doctor sent us a data dump of all kinds of statistics: how many people showing up at fever clinics, all this stuff about the crematories. And we knew something serious was happening.

The main thing we seized on is that the crematories had gone from running 4 hours a day to 24/7.

THACKER: How was he getting this information? Was he getting it from inside the government or pulling it off Chinese websites?

DUNN: He and a couple of other Chinese statisticians who were getting—some came from government websites—this included information on deaths in Wuhan before the pandemic. That information later disappeared, but luckily, we had saved it. Somebody had gotten this Tencent leak. That's a very important piece of the puzzle in this story that just got swept under the table.

THACKER: Tencent is this massive Chinese conglomerate that also has a news site.

DUNN: One of us had contacts in Wuhan, people in the medical industry, people at hospitals, people who were working with government agencies, all kinds of contacts. One of these people had gone around to the crematories and found out how overwhelmed they were.

I opened my email one night and there was this dump of information. People were feeling desperate to tell the world how serious the situation was. China was hiding how many people were getting sick and dying. Mike and I, and other Chinese doctors and statisticians, we started having these WebEx meetings. We didn’t trust Zoom because it’s Chinese.

We tried to figure out what was usable from this information and would immediately tell the story.

THACKER: How would you explain this to an average person?

DUNN: There were three papers that had taken early numbers and estimated the rate at which this disease was doubling and spreading to other people. A group of doctors in China had published in the New England Journal and then there was one published by Canadian researchers in the Annals of Internal Medicine. We decided to use an estimate right in between those other two, that was published in The Lancet, by researchers in Hong Kong who had gotten information on the hospitals, in Wuhan.

The Chinese doctor we were working with, who was in touch with others back in China, decided that was the most reliable estimate. But they were all close.

Using the prepandemic numbers of deaths in Wuhan, the leaked numbers of deaths after the pandemic, and the doubling rate of transmission, we could then make a model. Also, you can figure out when this must have started. We figured out it must have started between late September and the middle of October.

But we were being told it had started in late December.

THACKER: Right.

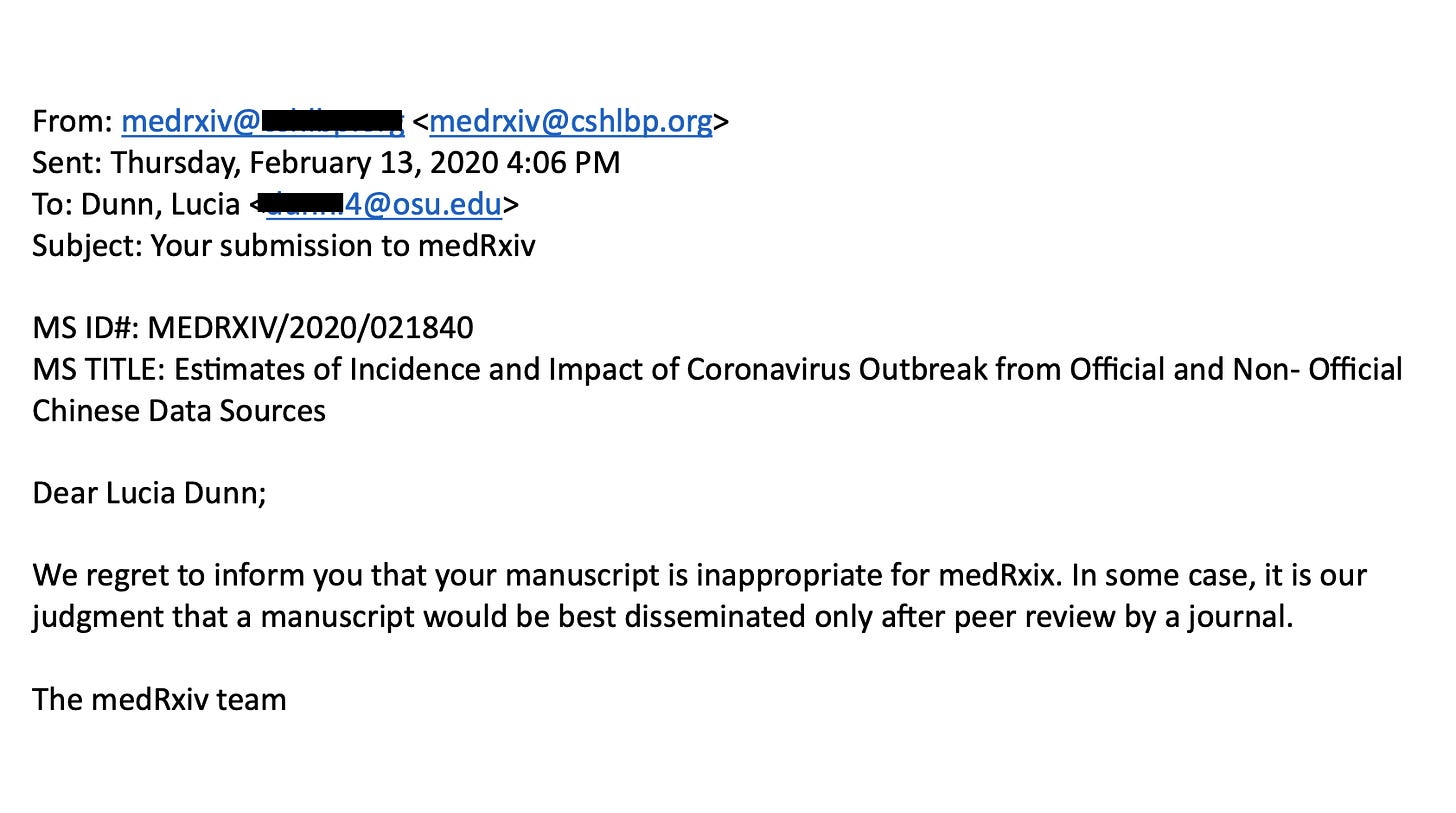

DUNN: So we wrote this up and we were racing to get it out, this was the first week of February of 2020. Four or five days later, we got a rejection from medRxiv, which is just a preprint site. The whole thing was like stepping into the Twilight zone.

But from day one, I knew this was not going to be a normal story. When we had our last WebEx meeting, I agreed to be the corresponding author for the paper and submit it through the system. And I said, “What's going to be the order of names on this paper?” That’s an important issue in academia, to determine who gets credit.

Suddenly there was this dead silence and then one by one, everybody at that meeting said, “Oh, I can't put my name on that. I have family back in China.”

THACKER: They were afraid.

DUNN: When we hung up that night, I was going to be the only person with a name on it.

Getting into the medical literature is very clubby, and they want to see a doctor’s name on the paper. I had a restless night thinking, “Here I am an economist, and I'm going to be the only person on this paper?” And then Mike contacted me the next day and agreed to put his name on it. That was a very brave act. He's a fearless guy.

So then we submitted it, but only with Mike and my name on it.

THACKER: How many helped to put the paper together?

DUNN: There were three others who would not put their name on it. But that's not the way things usually work.

THACKER: Normally people aren’t afraid to put their name on a medical paper.

DUNN: Then we get this email from medRxiv saying they weren't going to publish it. That was stunning because Mike and I were both tenured professors at known research institutions, and we were just trying to get it on a preprint site.

Putting it on a preprint site is the first step these days. You then get feedback and send an updated version to a journal. I had never heard of a preprint site turning down professors coming from established universities. [Laughs]

So then I sent it to two non-medical preprint sites and both of them immediately posted it. At one point like ten or 12,000 people had viewed or downloaded the preprint. So it was getting out there.

And then my university got a public records request to see all of my correspondence with researchers in China and with Chinese hospitals, etc…. We feel a directive came down from the Chinese government to do that.

That's my speculation. We do not know. But we didn't turn in anything in response because I had not had any personal correspondence with anybody in China. We got this information from people in America, who were getting information from people in China.

THACKER: So Chinese nationals, who were in America and getting information from people in China.

DUNN: Right.

So after we get the paper finally up on a preprint site, we …. [laughs] we sent it to like 50 or 60 journals. We kept a record. Mike thinks it was 60, I think it was about 50.

It would get immediately rejected. Not even comments back, like “We didn’t think you did your exponential growth model right” or “We think you calculated your confidence intervals improperly.”

It was always just “No, we regret to inform you….” [Laughs]

We even tried rewriting it, and sent out different versions. But after 50 or 60 journals, it never got accepted. So there it is.

THACKER: And the only prominent mention that you get is three years later in the Washington Post, with that one sentence.

DUNN: That's right.

Let me let me tell you about that Tencent leak. On two separate occasions, a government site reported official data that ended up on Tencent, a prominent Chinese site. We're calling it a leak, but nobody knows exactly what happened. But after they appeared, they were taken down within hours.

And the numbers of cases and deaths were vastly larger than the Chinese government then acknowledged. They were reported briefly and then immediately taken down. Some people were watching in the West and saw this happen. It got reported in India and The Taiwan News.

Leaked numbers appeared and then within hours, other numbers appeared much lower. But you could figure out that they had some algorithm that tracked the actual numbers, but were reporting much lower numbers that were acceptable to the Chinese Communist Party.

THACKER: When did you realize that this rejection of preprints was happening broadly? Sharri Markson reported in her book that Nikolai Petrovsky also said this happened to him.

DUNN: About a year after this happened to us, at the start of the pandemic, I saw an interview sometime in 2021 with Nikolai Petrovsky. He said the same thing was happening to him and other virologists who were also getting their preprints rejected. Petrovsky is a very well established, and respected guy.

He was looking at how the pandemic might have started with virus research, and we weren’t even trying to get into that. We were just trying to get out accurate numbers to the medical community.

I realized then that a part of the Western medical establishment has been captured by the interests of China. But, there were also these guys at the NIH who we know now were working with researchers at Wuhan. There were just a lot of people involved with this.

And it's very disturbing to feel like your medical establishment is not trustworthy anymore. But that's what I came to feel.

THACKER: We have these studies published in Science that try to establish that the outbreak must have been in December.

DUNN: We think earlier than December. Our analysis of the data finds it had to have started at least mid-October and maybe as far back as late September. Just looking statistically at how the virus was replicating, it started earlier than December.

THACKER: You and Mike also submitted a letter to Science pointing out statistical problems with one of those papers, but Science rejected it. Did that surprise you?

DUNN: Oh, no. Because by the time we had already had 50 or 60 rejections for our first very straightforward, mundane, non-controversial, paper on the number of deaths and cases in Wuhan. So, I was not surprised. It's just another nail in the coffin of [laughs] free thinking and science.

THACKER: Why do you think there is these papers being published in Science when there's so much evidence that this started before December. We have antibodies to the virus appearing in Italy….

DUNN: Yeah, well, [laughs]. There’s these vested interests. I attribute it to the fact that China seems to have gotten some sort of control over the Western medical establishment by just lavishing resources on Western academics and research projects.

When I was still actively teaching, not a week passed that I didn't get an email from some researcher in China who wanted to come and work for me, for absolutely free. He was funded by his own research institution in China, but he would be my assistant. Then he would do all this work for me and blah, blah, blah. And I’m in economics.

I'm sure this is more intense in science disciplines and medical research.

Even in economics they bring you over to China, all expenses paid, give you the royal treatment.

THACKER: Flood the zone with money.

DUNN: China pours money into the journals now. You must know the University of Chicago and Milton Friedman? Very conservative, free market economics stuff. They're famous for their economic journals.

There's something called the Becker Friedman Institute that seems to have latched onto Chinese resources. They put on these regular, big conferences with the Chinese, and they publish things that would make Milton Friedman turn in his grave, with this top down Chinese economic model stuff.

For somebody as old as I am, I remember how free market oriented they used to be. So that has happened, and it's happened all over academia. For a western medical journal with a relatively modest budget, all that Chinese money sloshing around might be able to buy influence.

THACKER: Well, Ian Birrell already reported on all the money the Nature journals get from China. Your hidden coauthors—Mike signed on—but the others who are also Chinese nationals now living in America…What was their takeaway of this entire experience?

DUNN: Oh, it’s just what they expected. [Laughs]

THACKER: Right.

DUNN: None of them were shocked. I was shocked.

Other Western academics that I've discussed this with, they have been shocked. But for people from China, it’s just what they expected. There's a Chinese underground with people plugged back into the country. They know incredible amounts of information, things that have not seen the light of day.

But they think some really rough stuff happened with that Wuhan lab. Some think there may be people who … who are no longer walking with us on the planet.

THACKER: Well, reporters disappeared, and one guy was thrown off a roof.

DUNN: But people I’ve worked with weren't really surprised. And that's why they wouldn't put their name on the paper.

Great interview. Illuminating: I had never thought about journal capture. That Friedman anecdote really puts it in perspective.

This article describes the same experience that Norman Fenton had in trying to publish papers on COVID.