Monsanto’s Ghostwriting to Influence Science and Media

While most ghostwriting scandals in science involve physicians, the agrichemical company ran a unique and sophisticated campaign to promote GMO technology and attack critics.

8 minute read

Back in 2010, I helped publish a decisive U.S. Senate report on medical ghostwriting, a process by which pharmaceutical companies draft a study and then publish it in a peer-reviewed journal, but with physicians signing on as authors—even if they may not be intimately familiar with the research and only lightly edited the text. Ghostwritten articles pollute medicine with corporate marketing designed to look like independent science. Despite our efforts, medical ghostwriting continues, and universities rarely punish professors.

Ghostwriting is most often exposed in biomedicine, but this is likely because there is a greater quantity of medical research, and because medical studies are more scrutinized and regulated. Nonetheless, ghostwriting has been uncovered in agriculture, based on documents made public through lawsuits and freedom of information act requests (FOIA).

Monsanto ghostwrote research and essays to promote the safety of the pesticide glyphosate. These essays were published on the websites of Monsanto front groups and in mainstream media outlets, while the studies ran in journals notorious for marketing corporate claims of safety in products such as tobacco, asbestos, and fossil fuels. Monsanto front groups then promoted these studies.

The ghouls of Monsanto

Awareness of glyphosate’s dangers continue to grow. The World Health Organization's International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) found glyphosate, the main ingredient in Monsanto's herbicide Roundup, to be a probable human carcinogen in 2015. Before this decision, internal emails show that Monsanto scientists began discussing ways to counter IARC’s findings. “[W]e would be keeping the cost down by us doing the writing and they would just edit & sign their names so to speak,” wrote Monsanto's chief of regulatory science, William Heydens. “Recall that is how we handled Williams Kroes & Munro, 2000.”

Fleshing out their strategy, Monsanto’s Heydens recommended publishing a study with the same data IARC had used. “Manuscript to be initiated by [Monsanto] as ghost writers,” Heydens wrote. “It was noted this would be more powerful if authored by non-Monsanto scientists.”

The Williams, Kroes and Munro 2000 paper appeared in Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology (RTP) and concluded, “Roundup herbicide does not pose a health risk to humans.” According to an expert report prepared for litigation against Monsanto, Heydens described the 2000 RTP paper as “an invaluable asset.”

The RTP paper was part of a project commissioned by Monsanto and undertaken by the consulting firm Intertek, which paid Williams and Kroes for their involvement. As the paper was being prepared in 1999, Monsanto’s Heydens emailed, “I have sprouted several new gray hairs during the writing of this thing...”

When the paper was ready to be submitted to RTP, Heydens emailed:

A clarification – there is one step missing – I will review the final manuscript with the reviewers comments incorporated (in revision mode so I can find them easily) before it is sent to the publisher. I will commit to conducting this review very quickly. Assuming the reviewers don’t throw any surprises (I’m especially thinking of Peterson), I can turn this back around with a very minimal investment of time.

Both Kroes and Munro had died when these documents came to light. Gary Williams refused comment, although the New York Medical College (NYMC) cleared him of any wrongdoing within days of being questioned by a reporter.

A year after Monsanto began plotting their 2015 attack on IARC, the journal Critical Reviews in Toxicology (CRT) published a special issue titled “An Independent Review of the Carcinogenic Potential of Glyphosate.” The declaration of interest section stated, "Neither any Monsanto company employees nor any attorneys reviewed any of the Expert Panel's manuscripts prior to submission to the journal.”

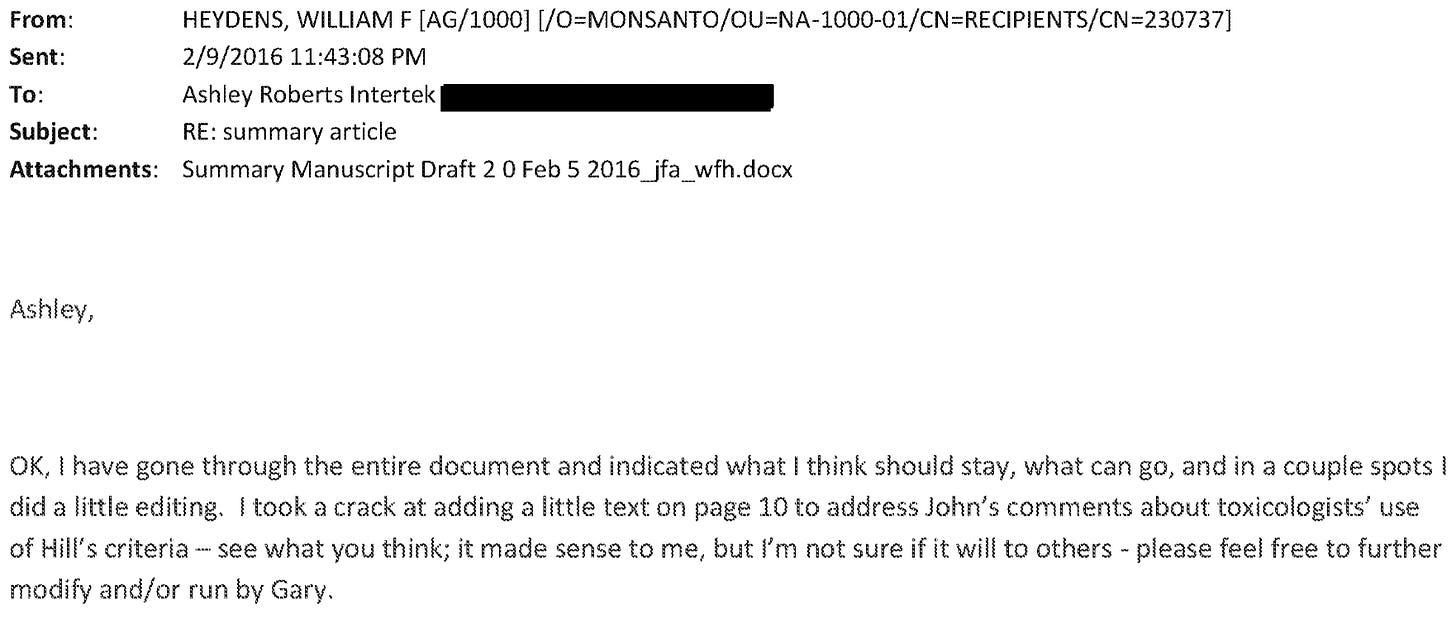

However, emails show that Monsanto had a hand in directing and editing the CRT manuscripts. In one email, Monsanto’s Heydens told an organizer of the papers, “I have gone through the entire document and indicated what I think should stay, what can go, and in a couple spots I did a little editing.” In his edits to one of the manuscripts, Heydens wrote, “I can live with any of the deletions below on this page if you are OK with them as well.”

Corporate vanity journals

The journal Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology has a long record of publishing industry friendly studies. In 2002, several academics and public-health activists sent a letter to Elsevier complaining that RTP lacked a transparency and a conflicts-of-interest policy, while many editors had ties to industry.

The long-term editor of RTP was Gio Gori, who was formerly the vice-president of the publisher of RTP—the International Society of Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology (ISRTP). For many years, ISRTP held their meetings in the offices of the law firm Keller and Heckman, which represents the chemical and tobacco industries. Gori had also been a paid consultant to the tobacco company Brown and Williamson. Court documents reveal that in 1991 the Tobacco Institute paid Gori $30,077 to write the paper “Mainstream and environmental tobacco smoke,” which was then published in RTP.

In 2017, Tufts University professor Sheldon Krimsky noted that industry consultants litter the masthead of RTP. That same year, the Journal of Public Health Policy examined tobacco documents to scrutinize the relationship between RTP and the tobacco industry. That study concluded, “These results call into question the confidence that members of the scientific community and tobacco product regulators worldwide can have in the conclusions of papers published in RTP.”

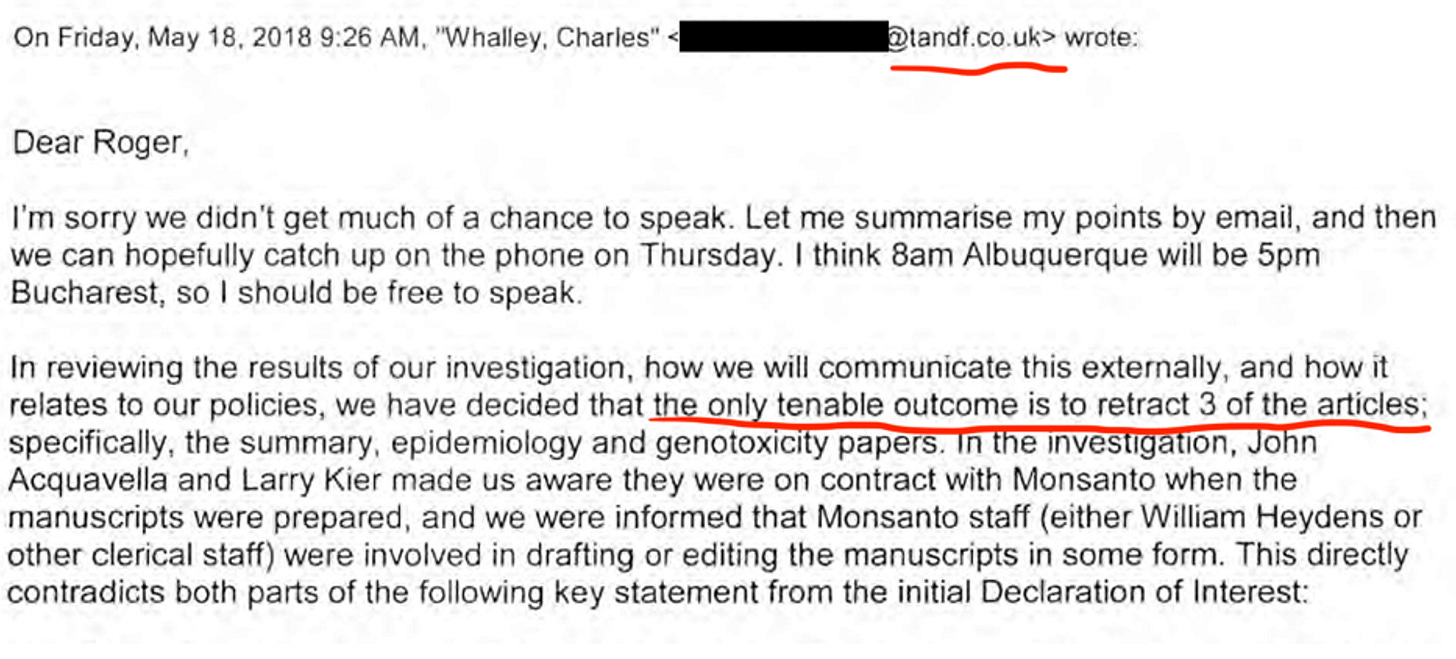

The journal Critical Reviews in Toxicology (CRT) also has a tawdry history. After several environmental groups later sent a letter to publisher Taylor and Francis detailing ethical misconduct in the 2016 special issue on glyphosate, the publisher launched an investigation.

“In reviewing the results of our investigation, how we will communicate this externally, and how it relates to our policies, we have decided that the only tenable outcome is to retract 3 of the articles,” a Taylor & Francis editor later emailed a colleague. But instead of retractions, the journal published a correction of the papers.

Other scandals have consumed the journal. In 2016, authors withdrew a paper in CRT that found asbestos does not increase the risk of cancer. Two of the authors disclosed in the study that they “have served and may serve again as experts in asbestos litigation.”

The following year a consultant who peer reviewed the paper testified in court. The consultant stated that he had previously testified in asbestos litigation on behalf of automakers, such as Ford, General Motors, and Chrysler, but said he had not disclosed these relationships to CRT when peer reviewing the study.

In April 2022, the Environmental Protection Agency proposed banning asbestos.

In a final example, the Center for Public Integrity published a 2017 report on fossil fuel industry manipulation of science to undercut clean air regulations. The report found a study in RTP and another study in CRT that drew conclusions at odds with years of science that fine-particle pollution is linked to premature death and chronic illness. Both studies were funded by the American Petroleum Institute.

Media promote these studies, as do front groups

In 2017, Monsanto gave Politico exclusive access to the court documents to write a piece on their battles with IARC over glyphosate safety. The article alleged that IARC engaged in the “questionable omission” of a 2015 study by the German scientist Helmut Greim. However, Politico engaged in their own questionable omission by failing to note that Monsanto had ghostwritten the Greim paper which appeared in Critical Reviews in Toxicology.

For example, in a 2015 performance evaluation, a Monsanto executive summarized his glyphosate-related activities, which included “ghost wrote cancer review paper Greim et al. (2015), coord Kier (2015) update to K&K, pushed for Sorahan (2015).”

The ghostwritten Greim review in CRT was also promoted on the website of the Genetic Literacy Project, which is run by former reporter Jon Entine. For many years, Entine maintained a close relationship with Monsanto executives, informing them of web traffic that promoted Monsanto’s business interests and inquiring if he should expand projects that helped the company. In an award-winning series, Le Monde characterized the Genetic Literacy Project as a “well-known propaganda website.” Monsanto/Bayer later admitted to funding them.

One of the oldest corporate front groups in America, the American Council on Science and Health, also promoted the glyphosate studies. When making the case to colleagues to fund ACSH, a Monsanto executive wrote, “You WILL NOT GET A BETTER VALUE FOR YOUR DOLLAR than ACSH.”

Ghostwritten media: it’s not just about science

To defend the herbicide glyphosate, Monsanto put together a comprehensive plan in 2015 to undermine IARC. As part of their “strategies” and “tactics” they identified several “industry partners” including the Genetic Literacy Project and Biofortified AKA Biology Fortified.

The website Biology Fortified promoted articles in RTP and CRT alleging the safety of glyphosate. Members of Biology Fortified include Kavin Senapathy—a contributor to the Genetic Literacy Project, and a co-author with Henry Miller, on multiple Forbes articles promoting GMO products.

In 2017, the New York Times revealed that Monsanto ghostwrote a Forbes article for Henry Miller that attacked IARC’s findings on glyphosate. In an email to Miller, a Monsanto executive asked, “Are you interested in writing more on the topic of the IARC panel, its process and controversial decision?”

“I would be if I could start from a high-quality draft,” Miller responded.

“Here is our draft...still quite rough ... but a good start for your magic,” the Monsanto executive responded.

Forbes removed several articles written by Miller and Senapathy. The Hoover Institution aggregated several Miller and Senapathy Forbes articles, but the titles now lead to dead links.

Internally, Monsanto also considered the need for other “third party” voices to counter IARC. To help on this, Monsanto hired Potomac Communications to plant favorable op-eds in the Washington Post and USA Today. The plan involved approaching the American Academy of Pediatrics to identify a “high profile author.” None of this appears to have happened, however Monsanto did succeed in planting various policy papers authored by academics.

In 2015, Monsanto secretly recruited scientists from Harvard, Cornell University and three other schools to write about the benefits of GMO technology. In the case of Harvard’s Calestous Juma, Monsanto suggested the topic and provided a summary and headline.

“Individually and collectively the topics were selected because of their influence on public policy, GM crop regulation and consumer acceptance,” wrote Monsanto’s outreach official, Eric Sachs, when setting up the papers. “To ensure that the policy briefs have the greatest impact, the American Council on Science and Health is partnering with CMA Consulting to drive the project.”

When the articles were ready to publish, the consulting firm contacted Sachs to notify him that Peter Phillips at the University of Saskatchewan had not sent his approval. “[W]ould it be possible for you to review the proposed edits on your brief on the costs of regulation and provide your approval?” Sachs then wrote to Phillips.

The papers were later published on the website of the Genetic Literacy Project.

As part of their “biotechnology outreach” Monsanto also began working with several professors to promote GMO technology through a website called GMO Answers—operated by the PR firm Ketchum PR. On several occasions, Ketchum PR sent a University of Florida professor statements which he then used nearly verbatim at GMO Answers.

Despite revelations nothing really happened

Bayer later bought Monsanto and announced that the company’s name would no longer exist. Nonetheless, Monsanto remains ensnared in litigation from people harmed by glyphosate.

Both the Genetic Literacy Project and the American Council on Science Health deny any influence by Monsanto and continue to publish claims that glyphosate is safe.

Although they remain tarnished from numerous scandals, the journals RTP and CRT continue to publish studies.

Henry Miller continues to publish in conservative and libertarian outlets such as City Journal and the Wall Street Journal, as well as at the Genetic Literacy Project. Kavin Senapathy continues to promote GMO technology messaging at outlets such as Slate and UnDark, an online science magazine. Scicomm!!!

Documents can be found at UCSF Industry Documents Library.

Great sleuthing! Much appreciated.

I'm sure the Disinfomation Governance Board will get right on this.