NAOMI ORESKES: DICHRON INTERVIEW

A candid conversation with science historian Naomi Oreskes, author of “Merchants of Doubt,” who exposed famed American scientists who denied climate change and dangers of smoking.

9 minute read

Over the last 15 years, Naomi Oreskes has become one of the most recognized names in science, not by churning out exciting new data or groundbreaking technologies, but by digging into the writings of America’s most famous researchers and the country’s most powerful corporations. In the early 2000s, she wondered why so many scientists seemed to doubt manmade climate change, so she delved into thousands of pages of scientific literature to see if their doubts were right.

In 2004, she published her findings in Science Magazine, confirming there was a scientific consensus that human activity was releasing greenhouse gases and changing the climate. Along with co-author Erik M. Conway, she later wrote the book “Merchants of Doubt” which followed a cadre of American scientists who had worked to deny the dangers of tobacco, and later denied climate change.

But exposing how scientists and corporations manipulate research has created detractors. Over the years, Oreskes has been attacked for her work, sometimes by the scientists she has exposed, recently by groups paid by fossil fuel companies such as ExxonMobil.

When The DisInformation Chronicle called up Oreskes, we caught her in the middle of writing her next book. Over several hours and emails, we talked about how scientists can sometimes be blinded by naïveté, politics cannot be ignored, and how disinformation constantly evolves. Here is an edited and condensed version of our talk.

DICHRON: I want to start when I first met you, around 2004, 2005. I had all these tobacco documents that I was going through and trying to figure out what to write. I was sending lots of emails to tons of people, because I didn’t understand what was happening. Nobody at the time seemed to know what tobacco had done to corrupt research and paying off scientists.

I was starting to notice that pretty much everyone at that time saying that climate change wasn’t real was saying ten years earlier that second hand smoke wasn’t bad for you.

ORESKES: Yes.

DICHRON: Someone put us in contact. We had a brief telephone conversation, and I remember very clearly hanging up the phone and thinking, “What is going on in my life? I’m a science writer. I talk to scientists. Why am I talking to a historian?” It was such an odd moment. What was going on with you at the time?

ORESKES: Well, my big connection was to Robert Proctor, a historian at Stanford. At the time, I was interested in how scientists come to consensus. My most recent book is about consensus, and a lot of people don't like the idea of consensus.

I got invited to give a talk at the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), and my lecture was on “consensus in science and how do we know we're not wrong?”

DICHRON: What does that term consensus mean? Because I think we have a sense that we know what it means. But what does it mean?

ORESKES: Consensus is just a fancy word for agreement. But I prefer the word consensus for two reasons. If you look it up, the dictionary will say “general agreement.” We're talking about a community decision. Second, the word consensus implies a process. And the process is really important.

We can identify when consensus in science occurs, but we know from history that sometimes the consensus can be overturned. I decided to use climate change as an example in my talk, and ask, “How do we know that climate science is not wrong?”

Already by 2003 there was a ton of stuff on the scientific consensus on climate change. I sat down to read all that—the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change reports, National Research Council reports.

But just because the scientific leadership says something about climate science, it doesn't mean the rank and file agree. The Pope says don't use birth control, but millions of Catholics do anyway. I started thinking, “How can I judge what rank and file scientists think?” And that's why I came up with the idea of doing the analysis of the literature.

Some people now give me credit for having invented consensus analysis. I thought I was just doing like a little reality check.

DICHRON: So, you gave a conference talk, and there was a slide talking about climate change. And that led to the 2004 scientific paper that found there was a consensus that manmade climate change was happening?

ORESKES: Correct. After the talk, the only thing that anybody wanted to ask about was that one slide. Many scientists had no idea that there was a consensus on climate change, because they were reading all these misleading things written by journalists, present company excepted, that was presenting climate change as a big debate.

I went home and realized I needed to publish this. As soon as my 2004 article in Science Magazine came out, I started getting hate mail, threatening phone calls. The whole kit and caboodle.

DICHRON: You got phone calls at your office or at your home?

ORESKES: No, at work. It wasn’t as easy to look up people's home numbers. A couple of months after that, I met Erik Conway, at an obscure academic conference. By this point, Fred Singer had started attacking me. I mentioned to Erik what was going on, and Fred Singer by name. Erik had been working on a book and he said, “Well, that's the same guy who attacked Sherry Rowland over the ozone hole.”

DICHRON: Sherry Rowland was a very famous scientist who figured out that certain chemicals that were used as coolants in air conditioners and refrigerators were creating a hole in the ozone, which was dangerous.

ORESKES: Correct.

DICHRON: What was Erik’s book about?

ORESKES: His book was about the work NASA had done in the field of atmospheric science. One portion of the book had to do with the ozone hole.

DICHRON: So, he had all this stuff about Fred Singer, in the process of collecting information for his book?

ORESKES: Correct. So, Erik tells me about Singer and I thought, “OK, this isn't about me. It's something much, much bigger.” Erik had this folder of materials on the ozone story. And you'll really love this. He hadn't done anything with it because he was writing a book about atmospheric science. And Singer attacking Rowland wasn't about the science. This was the politics.

DICHRON: Right. Because Erik is a science guy who doesn’t do politics.

ORESKES: Exactly. And in fairness to Erik, he works for NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, which wanted a book about the history of atmospheric science at NASA. He didn't see it as part of the job to explain why the scientists who had done that work had been attacked.

And at the time, I would have made the same choice as Erik. It's just how we thought. We thought that politics was separate from science. Erik sent me this material and it became the book we wrote called “Merchants of Doubt” because all the key players were there—Fred Singer, Fred Seitz, Bill Nierenberg, Bob Jastrow.

For me, it was kind of scary moment, because I knew all these guys. Bob Jastrow had been my colleague at Dartmouth. I didn't know Fred Seitz personally, but he was a famous enough figure in history. I started digging a bit more and that's when I hit the tobacco connection. I already knew Robert Proctor and the work he was doing on the history of tobacco.

I called him up and I said, “Have you ever heard of Fred Seitz?” It went from there.

DICHRON: For those who don’t know, what was your book, “Merchants of Doubt” about?

ORESKES: It was about climate change denial, about why people would reject the scientific evidence of climate change, specifically looking at the role these leading scientists had played in giving credibility to climate change denial.

They hadn't just denied climate change, they had denied the scientific evidence on a set of environmental and public health issues going back to tobacco. Singer and Seitz worked closely with the tobacco industry and had developed a set of techniques, the same strategies and tactics to challenge scientific information, even though they had no expertise in tobacco, or in the ozone hole. Or most things that they challenged.

DICHRON: Fred Singer, Fred Seitz, Bill Nierenberg and Bob Jastrow. Who are these people?

ORESKES: Well, they were all physicists. Some also had played an important role in the development of weapons, or rocketry, or other programs related to Cold War weapons systems.

And they all became climate deniers.

Fred Singer was a rocket scientist, literally. He had worked in the early history of the rocketry program. He had been the first director of the US National Weather Satellite Service and had been instrumental in the use of rocketry, to put a satellite into space for weather prediction.

Bill Nierenberg was a physicist by training who had worked on isotope separation for the Manhattan Project. He had gone on to be an important scientist for NATO, based in Paris. He was very proud of his French, and then he had become the director of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography. Scripps had huge contracts with the Navy to do work related with submarine and antisubmarine warfare.

That's where I met him. I had interviewed him on his oceanographic work. I've been at many events where he'd been—parties or campus events.

DICHRON: Who was Bob Jastrow?

ORESKES: Bob Jastrow was a physicist who worked for many years at the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies. He'd also written a lot of popular books about astronomy, planetary science, and had been a big television commentator back in the 1960s in relation to the Apollo program. He also taught at Dartmouth College for a number of years.

My first teaching job was at Dartmouth. So, you know, he was a colleague.

DICHRON: Let me tell you my history with Fred Seitz. Back in the mid-2000s, I worked at a science journal called Environmental Science & Technology or ES&T.

ORESKES: You'll appreciate this. My husband, all of his best work, he says, is in ES&T.

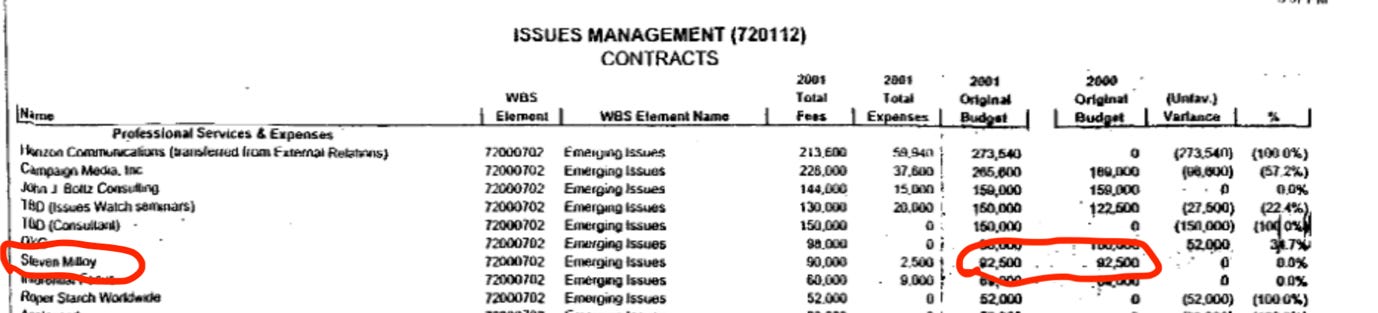

DICHRON: Oh, so you know the journal. I stumbled onto the tobacco and climate denial story, because of Steve Milloy. Everyone knows Milloy now as this guy who was quoted in the media as an advisor to the Trump EPA. Back then, Milloy was a science columnist for FoxNews.com, who had judged this science journalism contest run by AAAS. But in his columns for Fox, he was writing how climate change wasn’t real, smoking wasn’t dangerous, chemicals and pharmaceuticals weren’t dangerous.

ORESKES: Right.

DICHRON: While trying to understand who Milloy was, I got put in contact with Stan Glantz at UCSF, who was publishing on tobacco corruption. He told me about the tobacco documents and Milloy’s work with tobacco. So I wrote a piece about Milloy being a journalism judge, and then another exposing the money he was taking from tobacco.

ORESKES: Right. I remember that.

DICHRON: But then I started going through these tobacco documents. It was fascinating. I had no clue who Fred Seitz was. I was maybe eight years out of college, having studied biology, and didn’t understand there was corruption in science. I was reading about Seitz in the tobacco documents, and then figured out he had run Rockefeller University, which is a very famous institute. He'd also been head of the National Academies of Science.

I ran across a memo in 1989 from this tobacco guy, where he talks about arranging this appointment with Seitz. And he writes, “Dr. Seitz is quite elderly and not sufficiently rational to offer advice.”

ORESKES: Right.

DICHRON: This is only months after you see tobacco’s “best-evidence” magnum opus on diseases caused by smoking with Fred Seitz’s name as lead scientist. This struck me, “Oh, my God, they just use these people. This is a famous, important scientist and he's being totally used in his old age.” It was really disturbing.

ORESKES: Although I wouldn't say he was used against his will, because he'd already been working for RJ Reynolds for ten years before that. I don't think anything that they would have used in his name in the eighties would have been inconsistent with what he'd done a decade before that.

DICHRON: At the time, I had this very airy idea of science, that it solves all these world problems. And I'm realizing these lawyers and corporate consultants, they're the ones who really run science. Did you have these moments when you were going through these documents?

ORESKES: Oh, of course. It wasn’t quite so much about corporate America running science. For me it was more of, “Why are these people doing this?” Because these were famous scientists. Fred Seitz is a very famous name in the history of American science.

Jastrow was pretty big too. He played a big role in the space program. Bill Nierenberg was my colleague at UCSD. These were all big names in American science. I was trying to understand why they had done what they did. At the time a lot of people attributed science denial to illiteracy.

And that was how the scientific community was responding. That we just have to educate people, speak more clearly, communicate more effectively. I call this the Alan Alda approach. But these were some of the most brilliant scientists of their generation. It was not remotely plausible that they didn't understand the science.

DICHRON: Right.

ORESKES: The second idea is they just sold out for money. But I knew Bill Nierenberg pretty well and I had interviewed him many times. I've been at parties where he was. Bill was a rich guy, but I don't think he really cared about money.

He had consulted to the military industrial people in San Diego. It's not like he needed money; he had a really nice house. It seemed much more likely to do with ego, because he was a massively egotistical guy.

These people just always needed to be the center of attention.

For me and Erik, the question was always what was motivating these guys. None of this would have worked if it hadn't been a combination of money and ideology. If it was just money, people would have seen through it. By dressing it up in the ideology of freedom and liberty; that it’s about you're right to decide for yourself; the power and magic of the marketplace; and that you don't want the government to tell you what to do.

It gives it a credibility and believability for a lot of Americans.

DICHRON: You write about a guy named Fred Singer. I wrote an obituary on him when he recently died, because I had followed him in the tobacco documents and for years after while was quoted in the media as some type of expert. He was a particularly nasty person. Particularly what he did to a grad student, threatening him with a lawsuit to scare him. And I know that Singer came at you a couple of times. I got the sense that you were a little bit afraid of him.

ORESKES: Well, I wouldn’t say I was afraid of him, but I did see him as a dangerous person. I'm not afraid of snakes, but I recognize that snakes can be dangerous. I was worried about him pretty early on, because the first time I met him . . . he was a very dishonest person. And because he was so litigious, you had to be super careful what you said.

Now that he's passed, we can be honest about him. He had a reputation for threatening people. And as you said, he was a very mean person. Bill Nierenberg, for example, he wasn't mean. He was egotistical, and opinionated, and a bully, but he wasn't mean. Singer was mean.

Fred Singer called me when the American Meteorological Society was meeting in San Diego.

DICHRON: What year was that?

ORESKES: This was some time in the mid-2000s, before I knew who he was. He called me up at home and says he's a scientist and he's in town for the meeting. And he says he's a good friend of Walter Munk and that he would like to talk to me about my op-ed in The Washington Post, where I wrote about the consensus on climate change.

We met and then he started being really, really odd. “Well, why did I write that op-ed piece? And who was the editor that I worked with? Did they reach out to you?”

At a certain point, I started realizing, “Why is he asking all these questions, and why does he want to know who the editor was?” That's not a normal thing for a scientist to ask a fellow scientist. And it started getting creepy. I just said, “You know, I think we're done here.”

But I remember one thing very clearly. He says to me, “Well, good luck!” And he said it in this really nasty way.

And I said, “Oh, I don't need a luck.”

And he goes, “Oh, yes, you do.”

I'll never forget that. I’ll never forget the look on his face. So, I called Walter about this really extraordinary exchange, with his friend named Fred Singer. And Walter says, “Fred Singer is no friend of mine.”

DICHRON: Who is Walter Munk?

ORESKES: Walter was one of the leading oceanographers of the 20th century. And then Walter proceeded to tell me the whole story of Justin Lancaster, the grad student who I think you were referring to.

DICHRON: Yes. In Fred Singer’s obituary, I wrote about what he did to Justin Lancaster, because I felt people should know how Singer behaved. Who he really was.

ORESKES: So, then I was on high alert about Singer. And very soon after I discovered his role in “Merchants of Doubt.”

DICHRON: I was at a talk you gave a talk in DC in around 2006, when you were still researching your book, and you got very animated and angry at one point, in which you were talking about how some of these climate deniers threaten people. You wouldn't say the name, but I knew you were talking about Fred Singer.

ORESKES: Yes, that was his modus: to threaten people, to intimidate. And a lot of people would be intimidated. I wasn’t frightened, but I did take steps to protect myself. I did get legal advice.

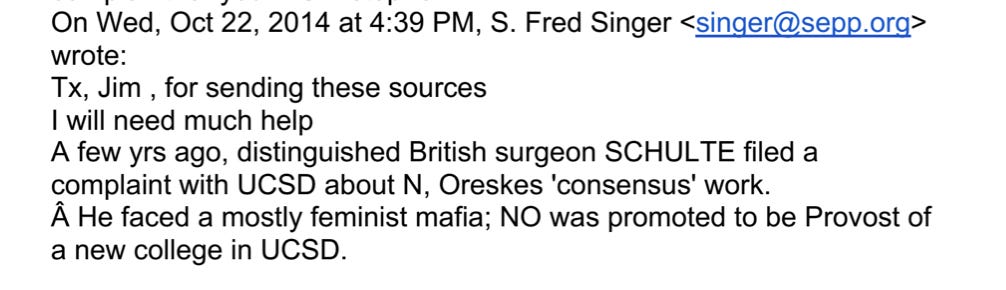

He did try to get me in trouble some years later, while I was still at UCSD. There was a letter that he sent after the movie version of “Merchants of Doubt” came out, to see whether they could sue me for defamation. He accused me of being part of the feminist mafia at UCSD. I got a copy of that because a friend somehow got on this mailing list.

Singer was involved in a number of efforts to try and discredit me. At a certain point, it became a point of pride. But in the beginning, it was certainly worrisome, because I didn't really know what I was dealing with.

This ends part-one of “A candid conversation with science historian Naomi Oreskes, author of ‘Merchants of Doubt,’ who exposed famed American scientists who denied climate change and dangers of smoking.” In part-two, she discusses identifying disinformation, and how industry recycles old, false arguments against Rachel Carson. To read part-two, click here.

Great interview. Just found you from Matt Taibbi's interview, looking forward to reading more.

Merchants of Doubt was such a pivotal novel for me in realizing The Science wasn't quite the utopian pursuit of knowledge I had hoped.