NAOMI ORESKES: DICHRON INTERVIEW (PART 2)

A candid conversation with historian Naomi Oreskes, on uncovering front groups, why the answer is always more science, and praising corporate PR for recycling (their same tired arguments!)

9 minute read

This is part two of “NAOMI ORESKES: DICHRON INTERVIEW” a three-part, candid conversation with Oreskes, examining the culture and history of disinformation in science. In part one, we discussed a cadre of famed American scientists who denied climate change and the dangers of smoking, and how some scientists and groups then began to attack Oreskes for exposing them. To read part one, click here.

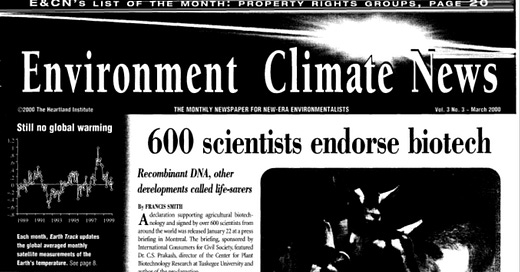

DICHRON: I want to take you and readers back to the year 2000, and a publication called Environment Climate News that the Heartland Institute published. Here’s some of the headlines for stories: “600 Scientists Endorse Biotech,” and it's written by a woman named Francis Smith.

A sidebar piece is “Monarch Butterfly Is Not in Danger, Revisited.” Another headline is “Medical Scientists Call Proposed DDT Ban Unethical.”

We’ve also got “Hot Air for the Millennium,” which features all these graphs trying to look all science-y. Then there’s another climate change story about computer models and the Kyoto Protocol. I like this clever headline that attacks the environmental group Earth First! which is titled, “Earth(worms) First: When CO2 Doubles Worms Process 35 Percent More Soil,” by Robert C. Balling Jr. He’s a well-known climate science denialist.

Why in 2000 was the Heartland Institute publishing stories that argued biotech is great, Monarch butterflies aren't harmed by GMO crops, physicians say DDT is awesome, and then all this stuff implying that climate scientists might be crazy?

ORESKES: This is sort of complex stew of things that are interconnected. One of the things we know about the Heartland Institute is that they have been funded by regulated industries, including many branches of the pesticide and chemical industries. They want to promote a worldview in which the activities of industry are all good and there's nothing to worry about. Anybody who says there is something to worry about is some kind of hysterical environmentalist, typically a hysterical female.

So, “Earthworms like CO2” [laughs] implies “Earthworms like CO2, so there’s nothing to worry about on climate change, it's all good.” A favorite one for them is to cherry pick data, to find some plant that grows better in an enhanced CO2 environment, or some worm. As if that somehow that invalidates the entire body of climate research, which it doesn't. This is something that they've been doing over and over. Most of these people have no expertise in the area that they're working on.

These people will pretty much say anything. They will be presented as experts but are not experts. And even when their claims are refuted, they speak them again and again. This has been well documented.

DICHRON: Let me delve into one of these people. The first headline is about “600 Scientists Endorse Biotech,” by Francis Smith. So, who is Francis Smith?

ORESKES: I have no idea. You have to tell me.

DICHRON: Francis Smith once ran Consumer Alert, is also known as “Fran Smith,” and is married to the founder of the Competitive Enterprise Institute. I see she has worked on the US perspective on European Union’s regulations of GMOs and was the editor of the Journal of Retail Banking.

ORESKES: [Laughs] Yes, I just pulled up her bio.

DICHRON: Here is something she wrote in 2010 for the Competitive Enterprise Institute:

“Is global warming the new apocalypse?” asks The Times of London in an article focusing on children’s fears about global warming in the context of a scare-mongering U.K. government advertising campaign to promote climate-change awareness.

Recently the Advertising Standards Authority ruled that some of the campaign’s print ads using nursery rhymes overstated the risks of global warming and were to be banned. But it passed on a TV ad that got almost 1000 complaints that it was too scary.

Why is it that a “Francis Smith” published a defense of the biotech industry for the Heartland Institute in 2000, but when I look closely, I find out she actually works at the Competitive Enterprise Institute or CEI, and also writes that climate science is “scare-mongering?”

ORESKES: Well, many of these think tanks—these libertarian, laissez-faire think tanks—they operate as interlocking directorates. You find many of the same people have been affiliated with them—sometimes at the same time, sometimes at different times. They work as an echo chamber. Someone from CEI will write a report and then that report will be cited by the American Enterprise Institute, or the Heartland Institute, as if it's a scientific report.

But when you actually look into it and say, “Well, who is the author of this?” You find the author is not a scientist. They work for an organization that is not a scientific institution, but rather a politically oriented think-tank. Almost all of these think tanks, if you go to their homepage, you find some variation of the same theme of promoting individual initiative, competitive markets, free trade, free markets. You know, freedom, freedom, freedom.

It's really about promoting unregulated or very loosely regulated capitalism.

Fran Smith, I'm looking at her bio at the Competitive Enterprise Institute. She focuses on trade and international issues. Well, that's fine. I have nothing against trade. She has a bachelor's degree from the University of New Orleans. Doesn't say what subject, but we can probably perceive it's not physics, chemistry, or science.

The point is, this woman has no obvious expertise in climate science, no expertise in biotechnology. This is a classic example of the pseudo expert, really an anti-expert. It's a person claiming expertise and using that claim to refute genuine experts.

DICHRON: Is history really the only way to understand this? When a disinformation campaign is happening in real time, it's hard to tell. But then lawsuits and investigations uncover documents, funding, and hidden ties.

ORESKES: I don't like to say that what I do is the only way to understand something. But the historical perspective helps us understand who these people are, their relationships to each other, who's funding, and what the ideological motivation is.

But I don't think you have to be a historian to see the problem. We discussed Fran Smith. So, if you're a journalist and you come across this newsletter by the Heartland Institute, and you don't have the time to do ten years of historical research. What can you do? You can do, what you and I have just now done.

You look at her Web page and you see a person who focuses on trade, who has a bachelor's degree but doesn't specify what topics, and clearly has no expertise in any scientific question that we're discussing. She's promoting some kind of position that is consistent with the views of the Competitive Enterprise Institute

If we go their homepage, we can very quickly see that the Competitive Enterprise Institute is dedicated to the free-market movement.

DICHRON: Since we have gone back in time, and I want to read you something you wrote:

There's more bad news for those watching the fires raging uncontrollably through Southern California. The prediction in the years ahead. Global warming will intensify our weather patterns, leading to an increase in the droughts and floods to which California is naturally prone. More droughts, in turn, will almost certainly mean more fires. More floods will mean more mudslides.

You didn't write this last summer, when those fires were going crazy out West. You wrote this for the Los Angeles Times in 2003.

ORESKES: Well, I guess I can feel pretty good. I got that one right.

DICHRON: What was going on at the time?

ORESKES: In 2003, I was reading the important climate science reports, trying to get up to speed, and that was the first time in my life that I had really dug in deep into the science. I'm just finishing reading all the stuff, and we had these big wildfires in San Diego, with the schools closed for a week.

I was home with my kids, trying to go to the beach, and the air was so thick you could scarcely breathe. There was all this ash falling, it was really, really creepy and scary. We turned around and went home.

Places were closed and we couldn't do anything. I just put two and two together, and that was the first op-ed that I ever wrote. I sent it to the L.A. Times, and about four hours later I got this phone call from this editor who said, “We really like this piece. Tell us about who you are and why you wrote this.”

That was the beginning. As I was counting just the other day—I’ve written 60 or 70 op-eds.

One mistake I think scientists make—it's sort of an occupational hazard—in science you don't get ahead by repeating the things we already know. You get ahead by finding some new detail. Scientists are bad at coming up for air and explaining the big picture to people.

By 2003, scientists were already saying that a place like California was going to see intensified weather, which would mean both worse fires during the fire season, but also heavier rains, flooding, and mudslides during the rainy season.

DICHRON: Right, we get the summer fires, which burn off all the plants. Then in Spring, the heavy rains come, there’s no grass and no shrubs to anchor the soil, so the hills slide. A part of the Pacific Coast Highway just fell into the ocean, last week.

ORESKES: Right, the basic science of that was pretty clear. I've tried to really focus on the first order effects, because there are a lot of details in climate change that are uncertain. You know, one time a congressman said to me, “I want to know what climate change means for my district.” That’s hard.

The accuracy of climate science is rather coarse. We know that the globe as a whole has warmed up. We can tell you something about the northern hemisphere, versus the southern hemisphere. We can tell you that Australia will get drier, the Pacific Northwest will probably get wetter. But if you say, “Well, what is this going to mean for Tacoma, Washington?” We can't really answer, on that level of detail.

Most people really don’t care what happens to the whole world. They want to know what's going to happen “in my neighborhood.” And that's still a hard question to answer.

DICHRON: There's another part in that same 2003 op-ed where you discuss countering climate change with weather modifications, like seeding clouds. You talk about this experiment in 1947 where these military researchers seeded the clouds of a hurricane trying to redirect it. The opposite happens and it makes landfall on the US coast.

And then here's what caught my attention and got me laughing. You write that the National Academies later found no convincing evidence that weather modification works. Nonetheless they suggested doing more research, even though “we won’t know whether weather modification can help solve our problems until 2030, 2040 or beyond.” [Laughs]

So, it's like, “Hey, this doesn't work. Let's do more research!”

ORESKES: [Laughs]

DICHRON: There seems to always be this “Send more money for more research” message followed by a second message, “We're going to find a new technology to get us out of this mess.” The answer is always more science.

ORESKES: Well, because that's what scientists do. I don't really blame them. If you hire a plumber, he’ll look to fix your pipes; if it's an electrician, he'll look at your wires. Sometimes scientists aren't actually the right people to answer the question.

Look at what's going on, covid-19. Look at this vaccine. This messenger RNA vaccine is a miracle of scientific progress. And the scientists who worked on it are heroes. But we can’t get the vaccine. I know one person who has gotten it.

If you don't have the organization for logistics, the social understanding to figure out how to distribute it, then all the best science in the world isn't going to solve your problem.

DICHRON: You keep bringing up this issue with scientists and their “I just focus on the science.” They pretend social issues outside of science don't affect science, but actually they do.

ORESKES: It’s a failure to see the big picture. If we have a good vaccine, then we have to distribute it, which in this case means keeping it really cold. And then we have to have people who know how to give vaccines, and vaccination centers. And we have to persuade people that the vaccine is safe.

It's a complicated story. But a lot of it has to do with the abandonment of public health in America, which has to do with the abandonment of the idea of government as a good thing, which is the book I'm writing now.

DICHRON: You wrote an article for a science journal around this same time in the early 2000s called “Science and Public Policy. What’s Proof Got to do with it?” In one section you discuss Rachel Carson, who wrote Silent Spring in 1962, which helped to launch the modern environmental movement. People know her name, but not many know what she went through, for writing a book about the harms from pesticides, specifically DDT.

A guy named Paul Müller had won the Nobel Prize in medicine for studying DDT’s use in disease control. So, she's bumping into a guy, who a decade prior, had won a Nobel Prize for DDT.

She writes this book, and here comes the attack. As you documented, critics say that her evidence was “anecdotal,” she had “exaggerated conclusions,” she was very emotional. She was criticized by corporate scientists, academics, the Department of Agriculture, even a committee for the National Academies of Science. The book was negatively, reviewed in journals such as Chemical and Engineering News, published by the American Chemical Society—which I left years back because it’s way too close to industry.

The Chancellor of the University of California at Davis, Emil Mrak, testified to Congress that Carson’s book was “contrary to the present body of scientific knowledge.”

If science gets it right, how did all this criticism get directed at her?

ORESKES: You know the answer. This is where big money did come in. Agribusiness was already big business. The United States and agribusiness had really thrown in its lot with the large-scale use of pesticides, as an essential component in the monoculture agriculture that they were pursuing. Many of these companies didn't think it would be possible to have agricultural productivity on the scale that they believed was necessary without pesticides.

Now, Mrak was wrong. It wasn't true that there was a scientific consensus. Among people like him, agriculturalists, they had persuaded themselves that these products were safe, but they hadn’t actually looked at the evidence. They were working on a particular model of toxicity that was left over from an earlier era. Before the invention of DDT and organic pesticides, people had used arsenic as a pesticide.

Arsenic is a toxic heavy metal. If you ingest it large quantities, you'll die.

DICHRON: Even if you're a corporate scientist who thinks pesticides are safe, you die if you ingest large quantities of arsenic.

ORESKES: What we now know is that DDT is an endocrine disrupting chemical. It interferes with hormones, so it operates very differently. It doesn't form the kind of acute toxicity that something like mercury, arsenic, or strychnine would. But in fact, it is toxic, and it does kill things.

Carson was dealing with the mental model of that time for what it meant for something to be toxic. And she was also synthesizing data from very different areas. She is a biologist by training. She's reading a lot of literature from people working for state fish and game departments, working for the National Parks Service, National Forest Service. These people were seeing this evidence of toxic effects on wildlife.

But when she goes to the toxicology community, she's confronting people who are working on an LD50 model. [NOTE TO READERS: The LD50 is a common method to measure toxicity. It is the amount of a substance which kills 50% of test animals, such as rats.]

Of course, she's also a woman in a male dominated field. She's writing in a popular style and a genre that's very different from what most scientists think is science.

The important thing is a bunch of reactionaries tried to say she was wrong, but they didn't succeed. There's this ugly period of attacks on her, but the President’s Science Advisory Committee reviewed the evidence and they concluded that she's right.

DICHRON: DDT was banned in 1972. But I'm reading your piece, and I see Emil Mrak testified against her to Congress. Do you know how I know that name? The administration building at UC Davis, where I went to school, is named after him. I’ve been in that building.

ORESKES: In fairness to him, he later apologized. He later admitted that he had been wrong. Unlike Bill Nierenberg, who has a building named after him at UCSD, and who never admitted he was wrong about anything.

DICHRON: You also write that Carson’s critics accused her of indifference to human fate, writing to the tune of a now forgotten folk song, “Reuben, Reuben.”

Hunger, hunger, are you listening,

To the words from Rachel’s pen?

Words which taken at face value,

Place lives of birds ‘bove those of men.

They were arguing that by writing about the harms of pesticides she was causing hunger in people. So interesting because that's the same thing going on today. There’s a meme promoted by cheerleaders for GMO agriculture and the pesticide glyphosate, that if you criticize either, you’re some “well-fed” White person causing starvation in Africans.

You had this “You’re causing hunger!” argument thrown at Rachel Carson back in the 60s and here it is again today.

ORESKES: Yes. I like to say, “These people believe in recycling.” They recycle their old arguments.

This ends part two of “NAOMI ORESKES: DICHRON INTERVIEW.” Next week, she ends our candid conversation with a talk about corruption in academic history, how funding skews scientists’ perceptions, and how we are all muddling through life trying to figure out what to believe. To read part one, click here.

this was a great read