Scientific American’s Mask Essays Are Rife With Fraud and Citation Sorcery

Making up facts to support ideological positions is a special kind of magic but has no place in modern research.

9 minute read

I’ve experienced two life altering episodes during my time on this planet: a war in the Middle East where I thought I might die, and a terrifying earthquake that shook the San Fernando Valley and launched me from my bed in the middle of the night. Both incidents taught me that when our environment loses stability and society wrenches out of order, social rules shift dramatically, causing some people to pivot and adjust while others thrash about, break, and fail to adapt.

Two essays on masks published by professors in Scientific American highlight—in ALLCAPS and boldface—the growing conclusion that THE COVID PANDEMIC BROKE ACADEMIC RESEARCHERS WHO PUT THEIR PERSONAL POLITICS AHEAD OF SCIENCE AND THE PUBLIC GOOD.

Sorry to shout, but it needs to be said: A life changing pandemic hit our planet and the learned class of people that we looked to for advice totally botched the job. Unfortunately, it wasn’t just on masks.

A recent New York Magazine investigation noted that the expert class also screwed the pooch when they clamored for lockdowns—a senseless, stupid experiment that devastated thousands of small businesses and working-class families. (“COVID Lockdowns Were a Giant Experiment. It Was a Failure. A Key Lesson of the Pandemic.”)

While both Scientific American essays on masks came out last year, I want to review how misleading they were because they ignored research and continue to put lives at risk. The COVID virus was not as deadly as we first believed in the pandemic’s early months, when experts predicted that 3-5% of the infected could die. But a virus this deadly might one day come along.

And when that lethal virus arrives, those at risk of dying have been made more vulnerable because the expert class taught them “masks work” and they can don a mask and carry on with their lives. These “masks work” ideologues have endangered the public by giving them a false sense of safety.

Now, let’s take a look at these fact-addled essays.

ESSAY 1: Citation sorcery

Scientific American published a silly “masks work” essay by three authors back in May 2023. The piece distorts available science and comes with this ironic title, “Masks Work. Distorting Science to Dispute the Evidence Doesn’t.” I tripped across this essay a couple months back—and after first ignoring it—I then took a closer look to figure out how they concluded “masks work”, when most evidence runs to the contrary.

The first thing you should know is that none of the three authors has any background in evidence-based medicine or epidemiology. Nor have any of them published any research of substance I could find in the peer-reviewed literature on masks or how to prevent or minimize virus transmission.

They’re just essayists and mask advocates, a background that does not inspire confidence.

Here’s their brief bios:

Matthew Oliver is an aerospace and electrical professional engineer, and citizen of the Métis Nation.

Mark Ungrin is a biomedical researcher at the University of Calgary’s veterinary school who studies stem cells and regenerative medicine.

Joe Vipond is an emergency doctor in Calgary, Alberta, and co-founder of the advocacy group, Masks4Canada.

Alerted to their lack of credentials, I then dove into the essay and found that they drew conclusions by making up research that didn’t say what they said it did.

I’m familiar with this process from the many years I spent investigating corruption in the pharmaceutical world where fraud is rife. When you read a corrupt pharma study, one of the ways you identify fraud is by examining the footnotes that a pharma-funded study cites and then popping open that cited study to confirm that it actually supports what they authors say it does.

In short, read the source material.

What you sometimes find is that corrupt studies will make claims, by citing source material that doesn’t support the claim. It’s what I call “citation sorcery.” A perfect example happened with opioids.

Back in 1980, the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) published a one-paragraph letter that claimed patients prescribed opioids for chronic pain were at low risk of addiction. We are now many years into an ongoing opioid epidemic caused by the pharmaceutical industry and know this is false.

In a 2017 letter also published in NEJM, David Juurlink at the University of Toronto noted the 1980 letter actually provided zero evidence to support the claim that patients were at low risk of addiction when prescribed opioids for chronic pain. It was a medical claim that was just made up. Below is that 1980 letter in NEJM.

Nonetheless, academic researchers then cited this misleading 1980 letter over 600 times in the academic literature, with a sizeable increase in citations after Purdue introduced Oxycontin in 1995.

Here's what Juurlink found:

In conclusion, we found that a five-sentence letter published in the Journal in 1980 was heavily and uncritically cited as evidence that addiction was rare with long-term opioid therapy. We believe that this citation pattern contributed to the North American opioid crisis by helping to shape a narrative that allayed prescribers’ concerns about the risk of addiction associated with long-term opioid therapy.

In short, it was citation sorcery—researchers spinning scientific magic to promote opioids by citing a fake claim that told them what they wanted to hear, even though it was evidence free.

The Scientific American authors played a similar citations sorcery game by making claims in their essay based on links to research that didn’t provide evidence. Arthur C. Clarke once said, “Magic is just science we don’t understand yet.” To try and understand the magic that went into this essay, I emailed four examples of citation sorcery to Mark Ungrin, one of the essay’s authors.

Here’s the first example:

But when you click on the link Ungrin and the other authors provide for the evidence “masks work” it doesn’t take you to a study or actual research. It’s an opinion piece published in JAMA. You can read that JAMA essay here.

In my email to Ungrin, I asked, “I'm trying to understand if you think an opinion should receive the same degree of credibility as a clinical trial, or a systematic review.”

Here’s the second citation sorcery example in the essay:

The passage “despite decades of evidence of their efficacy” links back to a 1998 study published in an obscure journal that discusses microbes, which are several orders of magnitude larger than viruses. The study states nothing about N95s stopping viruses or influenza, as Ungrin and his co-authors claim in the paragraph. (The paper is behind a paywall, but I uploaded a copy for inspection.)

The third example of citation sorcery is this passage:

This link for “decades of widespread and successful use” takes you to a study in a peer reviewed journal that discusses the history of masks, but makes no claims about their usefulness in stopping the spread of viruses (“History of U.S. Respirator Approval (Continued) Particulate Respirators”).

“I don't understand what this has to do with the topic at hand,” I emailed Ungrin.

A fourth example of citation sorcery happens here:

Nothing in any of these links codifies anything about protection from viruses.

The study linked to in the passage “been validated over decades” discusses mycobacteria. Again, mycobacteria are orders of magnitude larger than viruses. So why is this study being cited in an essay about viruses? (This study is behind a paywall, but I uploaded a copy for inspection.)

This would not have been difficult for an editor at Scientific American to fact check, because the study emphasizes that it has nothing to with viruses in the title: “Respiratory protection against Mycobacterium tuberculosis: quantitative fit test outcomes for five type N95 filtering-facepiece respirators”.

“This is very confusing,” I emailed Ungrin. “Can you please explain why these references don't seem to support the claims made in the piece?”

“There were limitations on how many references we could fit into the SciAm article,” Ungrin emailed me.

Ungrin’s response ignored that he and his co-authors made multiple false claims in their essay without supporting evidence. Or maybe there’s evidence, but Scientific American’s editors wouldn’t let them include it because there’s a limit on hyperlinks?

Ungrin added an additional 1000-word explanation in his email to me that contained other questionable points—essentially an essay explaining his Scientific American essay.

Oh, but it gets better.

Ungrin’s “Masks Work” essay was then laundered and amplified through another Scientific American essay published in November 2023, by Harvard historian Naomi Oreskes, “What Went Wrong with a Highly Publicized COVID Mask Analysis?”

ESSAY 2: Laundering and amplifying

The Oreskes essay argues that something went terribly wrong with the Cochrane Review on masks. For almost a quarter century, Cochrane Reviews have represented the epitome of systematic and independent science to determine the efficacy and safety of medical treatments.

In her essay dogging the Cochrane Review on masks, Oreskes makes two main claims: masks work (surprise!), and the Cochrane Review ignored research by “dogmatically” relying on randomized controlled trials.

Both arguments are dogmatically wrong.

Here’s the argument that “masks work”:

When you click on the link for “masks do work”, guess what is takes you to? It takes you to the muddle-headed Scientific American essay rife with citation sorcery by Mark Ungrin and colleagues.

This is exactly what happened during the opioid crisis, when academics cited the evidence free 1980 letter in NEJM to promote a message that opioids were not addictive. It’s citation laundering.

In an email to Oreskes, I asked her why she cited as proof “masks work” an essay in Scientific American that didn’t contain evidence that mask work.

“Sometimes editors add links to other Sci Am stories. I cannot confirm that that happened here, but it may have,” Oreskes explained. “I generally try to link to peer-reviewed science, but sometimes that science is behind paywalls, which doesn’t work for a popular magazine.”

Fair enough. But her second error is also troubling.

In several passages, she alleges that Cochrane ignored evidence that masks work, because they have given in to “methodological fetishism” and are overly reliant on randomized-controlled trials or RCTs. Oreskes then cites a couple of questionable studies that found masks do work, some of which have already been picked apart by experts.

I’m not going to dispute the claim that different types of research have value and that physicians might be overly reliant on randomized controlled trials. That’s a topic for a different essay.

But there’s no need to discuss this, because Oreskes’ claim that Cochrane is overly reliant on randomized controlled trials is simply wrong.

Here’s a pertinent passage making this allegation:

Oreskes’ allegation that Cochrane ignored evidence that didn’t “meet its rigid standard” for RCTs can be proven false simply by reading the Cochrane review. Sadly, ignoring Cochrane but then having an opinion on Cochrane is not unique to Oreskes.

Beginning in 2006, Cochrane reviewed the evidence that “masks work” and found no evidence masks stop community spread of viruses. Cochrane updated this review in 2007, in 2009, in 2010, and again in 2011.

Each one of those reviews found no evidence that masks work to stop viruses and relied on epidemiological or observational studies—the very type of studies that Oreskes states that Cochrane should have been included. Why did Cochrane do that?

Because there were not enough randomized controlled trials to provide sufficient evidence on masks.

It was only in the 2020 update that Cochrane authors relied solely on randomized controlled trials. How do we know this? The authors of the Cochrane review explained this to anyone who bothered to read and understand the research on masks.

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and cluster‐RCTs of trials investigating physical interventions (screening at entry ports, isolation, quarantine, physical distancing, personal protection, hand hygiene, face masks, and gargling) to prevent respiratory virus transmission. In previous versions of this review we also included observational studies. However, for this update, there were sufficient RCTs to address our study aims.

The Cochrane authors relied on RCTs again in their 2023 update—again because they had sufficient RCT studies. They could have included high quality observational studies, but why do that when you have enough randomized controlled trials?

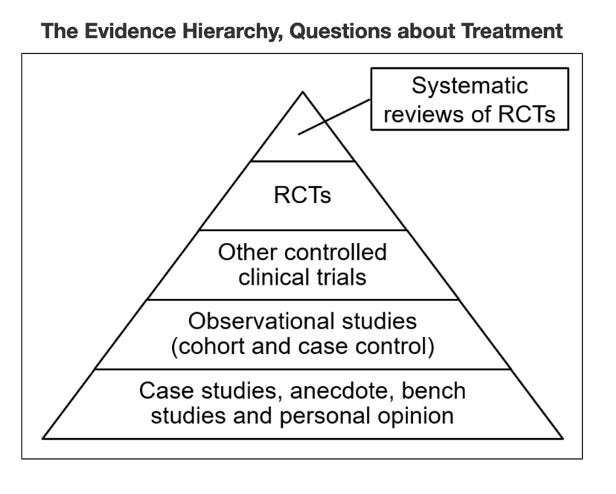

What Oreskes the historian fails to grasp is that medicine relies on a hierarchy of evidence that ranks studies based on the strength and precision of their research methods. What she calls “methodological fetishism” is a process medical experts put in place to try and remove bigotry and bias (citation sorcery!) that is rife in biomedical research.

This research module at Mount Sinai explains this rather clearly.

And nowhere in the hierarchy of evidence do we find “essay in Scientific American.”

Oreskes is also big on climate change. I sense a pattern.

I canceled my long standing subscription 2 years ago.