Seeking Transparency and Reform in Medicine & Science

A Senate campaign brought some transparency to medicine, but problems persist in science and much more needs to be done.

8 minute read

I gave a lecture last week to students in MIT’s Health Sciences and Technology (HST) graduate program about exposing and trying to fix problems of bias and corruption in science and medicine. Many of these students are pursuing both medical degrees and doctorates and all of them will be entering the workforce as leaders in biomedicine—and I was hoping to help them understand problems they will encounter in their futures, as well as possible solutions.

My talk can also help readers understand how corporations influence decisions made in biomedicine and other areas of science. During the lecture, I discussed multiple investigations I ran while employed as a Senate Investigator—uncovering corruption while trying to fix problems at agencies and also advancing legislation. Few people outside of this specialized field of congressional investigations understand how committees seek to find and fix problems in society, so let me explain.

From around 2007 to 2010 I worked as a Senate Investigator for Senator Charles Grassley on the Finance Committee. Grassley made a name for himself in the early 80s exposing bloated defense contracts and cost overruns at the Department of Defense. If you’ve ever read about the Pentagon paying $450 for hammers, $640 for toilet seats or $7,600 for coffee pots, that was stuff Grassley investigations made public. Since those years, Grassley has always employed staff to sniff out corruption, and when I was hired, he was the top Republican on the Finance Committee.

A committee’s jurisdiction gives you power, and Finance is the most powerful committee in the Senateo—overseeing tax policy, trade, Social Security, and the two federal healthcare programs—Medicare and Medicaid. These two healthcare programs now spend more money than the Pentagon, and investigators on the Committee had been digging into corruption inside the pharmaceutical industry.

Pharmaceuticals make up about 15% of healthcare costs, and the United States federal government is the world’s largest customer for the pharmaceutical industry—paying for about 1/3 of all the drugs bought in America. In fact, the federal government is such an important customer, that during one interview with a pharmaceutical executive, he explained to us that drug companies will study diseases based on how much money they think they can get the federal government to pay for the drugs.

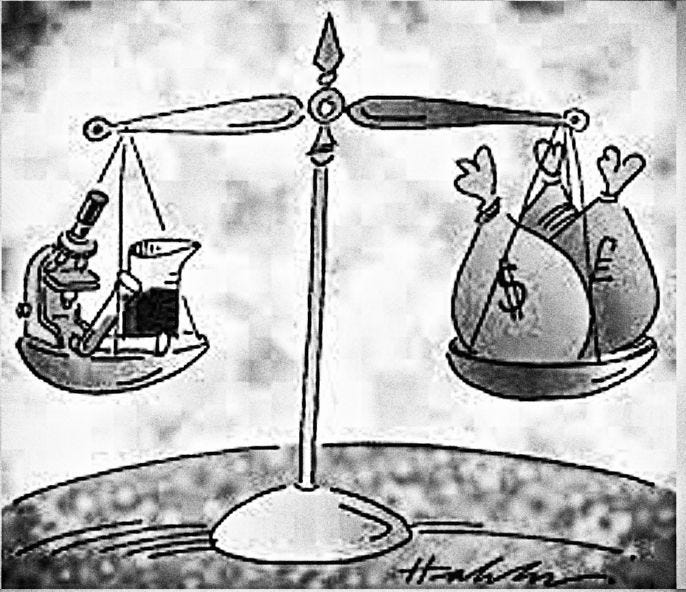

Think about this the next time you hear a pharmaceutical executive argue that they research diseases to save lives. The reality is that they do research to make money. There’s nothing wrong with this, but that’s the reality.

Pharmaceutical companies know they have a desperate audience. People are willing—eager, even—to pay top dollar for drugs, because they have always valued their health. To say this isn’t anything new, you just need to look at these two quotes that go back well before anyone had heard of Pfizer or GlaxoSmithKline:

It is health that is real wealth and not pieces of gold and silver.

—Mohandas Gandhi

A wise man should consider that health is the greatest of human blessings.

—Hippocrates

The Congressional Oversight Process

Again, much of congressional oversight is not well understood, even by most congressional staffers. For those with intense interest, see this several hundred page manual on congressional oversight written by legal expert Mort Rosenberg. For the rest, here are the highlights:

The power to oversee or investigate is implied rather than enumerated in the Constitution.

The Supreme Court has affirmed the power of Congress to investigate.

Statutory Authority can be found in several whistleblower protection laws going back to the 1912.

I started investigating industry payments going to doctors after a meeting one day with my boss, the Chief Investigator of Finance. We had long been troubled about pharmaceutical money moving around inside the healthcare industry and influencing doctors to prescribe more and sometimes dangerous drugs. To give you a sense of how much money there is in pharma, I dug up this quote from Tachi Yamada, who was once the head of research at GlaxoSmithKline: “Pharma was an industry in which it was almost too easy to be successful. It was a license to print money. In a way, that is how it lost its way.”

To lay all this out, my boss drew a schematic on a yello legal pad with Big Pharma in the middle and arrows showing how the money was moving around. And since Tachi Yamada said that pharma had a license to print money, I’ve replaced “pharma” with a money tree.

It was a lot of money swirling around—incredibly complicated—but I knew that doctors operated under a principle of putting patients first, so I said we should focus on the doctors and try to get them to behave more ethically. We knew the drug companies were paying doctors to buy influence, and that physicians were critical to pharmaceutical corruption:

physicians run pharma’s clinical trials

doctors chair panels that approve and recommend drugs

physicians give talks that influence prescribing practices

physicians write prescriptions.

But how could we expose this?

We quickly found a way. It turned out plenty of physicians were pretty greedy.

Right around this time, the New York Times published a story titled, “Psychiatrists, Children and Drug Industry’s Role” that discussed this very topic of money that doctors were taking from the pharmaceutical industry. In one case, an academic physician whose university salary was $196,310 explained why he gave marketing talks for drug companies to make extra money. “Academics don’t get paid very much. If I was an entertainer, I think I would certainly do a lot better.”

Another physician had run a clinical trial in 2002 for AstraZeneca that found efficacy for one of their drugs to treat pediatric bipolar disorder. This study was the only paper available on the topic of pediatric bipolar disorder and later led to fairly broad prescribing practices for the condition. When the New York Times reporters asked the professor how much she had taken from AstraZeneca, she told the paper, “Trust me, I don’t make much.”

When I read this, I started laughing and walked into my boss’s office. We then called the University of Cincinnati where she worked and asked to see her financial disclosure forms. When I read them, I learned that AstraZeneca had paid her $100,000 in 2003 and $80,000 in 2004. Call me crazy, but $180,000 in payments from one drug company over two years sounds like a lot.

But some months later, we got better information from AstraZeneca: they had actually paid her way more money that she had disclosed to her university. I put that into a chart that we then sent to the University of Cincinnati along with the National Institutes of Health, which had given her a research grant. The National Institutes of Health requires universities to report the conflicts of interest of professors on grants, but if she was underreporting her pharma money to her university, it was obvious the NIH didn’t know the whole story.

Realizing this was likely happening all over the country and not at just one university, I then gathered the names of several academics physicians, who experts told me were taking money from pharma, and sent their universities letters telling them to turn over their conflict of interest forms. I then sent letters to the biggest pharma companies asking them to tell us how much they had paid these same doctors.

We then started building charts, showing how much these doctors had disclosed taking from pharma, versus how much the companies said they had actually paid them. In effect, I was running a political campaign to embarrass academic physicians and the pharmaceutical industry for conspiring to hide all this money, and to pressure them to support a bill I drafted that we called The Physician Payments Sunshine Act. This bill required companies to report payments made to doctors.

Over several months, I then rolled out several examples of academic physicians who’d taken money from industry, but had not accurately reported that money to their universities or the federal government. These academics included the chair of psychiatry at Emory University, the chief of spine surgery at UCLA, several psychiatrists at Harvard, a spine surgeon at the University of Minnesota, and numerous other examples.

Pretty much anywhere and everywhere I asked questions, I found hidden money.

In the end, the Physician Payments Sunshine Act got passed as part of healthcare reform, also called Obamacare. You can now look up your doctor on the Open Payments website to see if he or she is taking money from companies and why.

We also got some reforms passed at the National Institutes of Health, which required better disclosure of conflicts of interest. The NIH even proposed having universities post their professors’ conflicts of interest, making them available to everyone. But at the last minute, Harvard and other universities went to the White House and lobbied to get that provision removed and keep this money hidden from the public.

Still, these changes were a remarkable improvement. Scholars studying financial influence in medicine have used the Open Payments site to track financial influence in medicine from the opioid industry, and lawyers access the database for lawsuits. The New York Times accessed the site to report on hidden financial influence in oncology at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York, and I used information from Open Payments to write an award-winning story on undisclosed financial influence on the panels that approved the COVID-19 vaccines.

Unfortunately, there are few conflict of interest rules in areas outside of medicine. For example, I just wrote an investigation for The BMJ about all the fossil fuel industry money that has been pouring into universities to shape academic research on climate change. Many of these departments lack strong policies on financial disclosure as exist in medical centers.

Problems persist …..

Another great piece. At 33 paid substack subscriptions, this is by far my favorite (sorry Taibbi). Consider bookmarking this post as your introduction so new readers can better understand your lens.

Had no idea you were behind the open payments website. Pretty amazing. Used it to double check my wife just now who racked up $500 in "payments" in 2021 :) https://imgur.com/a/VVYUqw9

I wonder if that was what lead to the decline of the "Drug Dinners" my wife used to attend all the time in medschool? Pharm and device manufacturers used to take swaths of residents all the time to high end steakhouses to pitch their wares, that seemed to have died out in the late 00's.

Important work to teach/ inform the next generation. Most have no clue.