NAOMI ORESKES: DICHRON INTERVIEW (PART 3)

Continuing our candid conversation with science historian Naomi Oreskes, on tobacco influencing historians, money shaping science, and how we all muddle through life trying to get answers.

9 minute read

This ends our three-part series “NAOMI ORESKES: DICHRON INTERVIEW,” a candid conversation with Oreskes, examining the culture and history of disinformation in science. In part two, we discussed how to uncover front groups, why the answer is always “more science,” and praised corporate PR for recycling (their same tired arguments!). To read part two, click here. To start at part one, click here.

DICHRON: As you were doing research for “Merchants of Doubt” in the mid-2000s, I was going through the tobacco documents and following the money, and concluded that if you had the word “free” or “freedom” in the name of your organization, there was a 95 percent possibility you were taking money from tobacco.

ORESKES: Absolutely. When you called, I was working on the Reagan speeches, where Reagan uses this phrase about the “magic of the marketplace.” He also uses the word “freedom” constantly. One speech I was just looking at, it had seven paragraphs and he uses the word “free” or “freedom” seven times. This becomes the drumbeat of the right-wing ideologues, but it's linked to these corporations trying to protect their freedom to make the biggest profits.

Money people fund the ideological people, and the ideological people give the money people cover.

DICHRON: I always say, “Freedom isn’t free. It requires huge bags of corporate cash.”

ORESKES: Exactly.

DICHRON: I grew up thinking science solved the world’s problems, and humanities was kind of worthless. But reading the tobacco documents totally reversed my thinking. The scientists were the nerds who can do math and study hard subjects. But they’re not that smart, because the people actually controlling things are the lawyers and consultants.

ORESKES: A bunch of us went into science thinking that this was the best thing we could do with our lives. We thought, “If we just do good science, and we gave the world good information, they would say, ‘Oh, that's great. Thanks for sorting this out; we’ll go fix this problem.’”

We were trained, as you already said, that we didn't have to study history or politics. Because at best it was soft stuff; at worst, it was useless. And now I feel exactly the opposite.

DICHRON: So, let's get into the history of science, because it ain’t always a nice history.

ORESKES: It’s complicated.

DICHRON: John C. Burnham, professor of science history at Ohio State, was also a tobacco consultant. He's right there in your wheelhouse, served as president of the American Association for the History of Medicine. He helped tobacco litigation in the eighties, recruited historians, David Hartley of Oxford and David Musto of Yale, who were allocated over $300,000 for historical work, that never mentioned their tobacco funding.

After getting this tobacco money, David Musto then wrote a feature for Scientific American in 1991 that downplayed the dangers of addictive drugs. Musto tried to argue that attempts to control addictive drugs were being driven by prejudices and not science.

History doesn't necessarily have a nice history, does it?

ORESKES: Well, anything that people are involved in, there's going to be corruption, right? And historians, scientists, journalists are all subject to corruption. Scientists are very naive about politics.

I've certainly seen the phenomenon where scientists think that, because they're scientists and because they're smart, they won't be corrupted by money. They think that they can take money from the tobacco industry and that will not influence their work. You and I wrote a piece together about the need for financial disclosure.

I wouldn't say that the whole field of history of medicine is crap because of John Burnham, but there were quite a few who took the money and claimed that they were just objectively looking at the history of the tobacco industry. I think we both know that doesn't pass the sniff test.

I worry more about the funding effects that permeate large areas of science. As you know better than I do, biomedical research is massively permeated by corporate pharmaceutical money. The whole system is now being influenced by the interests, the orientations, the desires of the pharmaceutical industry.

I don't actually feel like that applies as much in Earth science, because most Earth science research is not corporate funded. But a very worrisome thing has happened in the last 10 years or so. All across America, they have these energy and environment centers that are funded by the fossil fuel industry and that's, you know, really, really terrible.

DICHRON: It's what I wrote about in the history of biomedicine where tobacco funded all this university research starting in the 1950s. It's a recapitulation of history, with the fossil fuel industry today. But unless you know the history, you're not going to see it.

ORESKES: You see it, but you don't think it's anything to notice. I have a lot of colleagues who have accepted money from the oil and gas industry and will insist that it doesn't influence their work at all.

But if I point out that the tobacco industry saturated biomedical research in the mid 20th century with tobacco funding, including major medical schools across the country. And independent researchers have looked at this and have shown scientifically that this research was influenced. When they hear that, it makes them at least stop and think.

DICHRON: I just peer reviewed this study for a leading medical journal about corporate funding of research, and the authors mention tobacco as an example of corruption. I feel that tobacco is a crutch allowing people to ignore what is happening today, because it’s not as bad as tobacco.

ORESKES: That somehow, it's tobacco exceptionalism.

DICHRON: I like that idea, yes. In my review, I told them to point out ongoing corruption happening right now in science. Several studies document corruption of the science of soda causing obesity and the pesticide glyphosate. But for many scientists, they seem to think it was only tobacco, something that happened when they were kids.

ORESKES: A lot of scientists are fairly quick to dismiss things from the past, because they assume that it was an error of the past, that we remedied. But in most cases, we didn't remedy at all, because we didn’t actually do anything.

Tobacco got exposed, not because of anything scientist did, except a few like Stan Glantz at UCSF. The exposure of tobacco malfeasance was the work of lawyers. Scientists helped, like Stan Glantz’s group, Lisa Bero, and all of us folks at UCSF. They helped and have done really important work. But it wasn't the scientific community.

In that sense, I think many scientists are very complacent.

Also, they don't understand how influence works because they’re being accused of becoming shills for the industry. Of course, we know people who are shills, for example, Willie Soon of Smithsonian took large amounts of money from industry.

DICHRON: It’s been reported in the New York Times and other outlets.

ORESKES: There's an example of somebody with a direct, unequivocal industry tie. But in most cases, money’s effect is more subtle. It often operates in terms of what you do and don't study.

At my home institution we have this giant project—our solar, geoengineering. Why are we putting so much effort into that instead of studying energy efficiency or, better batteries for renewables or grid integration?

There was this great study by federal scientists that basically showed you could power the entire United States with solar and wind, if...if, if, if you integrated the grid well. Integrating the grid is largely a political problem because of regulatory obstacles. It's telling that, one of the key things that we need to do to get off fossil fuels in America is essentially a political and regulatory problem.

So, do we have a massive effort at Harvard to figure out how to clean up the regulatory obstacles that prevent grid integration? No! [Laughs] Maybe somebody down in the basement of the law school is working on it. But I know at least a dozen of my smartest colleagues working on solar and geoengineering.

Why is that? We have a big famous corporate sponsor who's interested in solar geoengineering, who has given millions of dollars. We don't have the deep pocketed philanthropist with money to fix the regulatory challenges.

DICHRON: You have this piece in 2015 in The Guardian about a new form of climate denialism, and you call out a bunch of scientists who argue we must use nuclear energy, because renewable sources can’t supply our energy needs. After you write this, Michael Specter at The New Yorker writes this kind of snotty hit piece on you, “Hey, look at me, everybody. I’m an expert on denialism and Oreskes is absurd.”

What I thought was funny...in 2019, you write another piece about the false promise of nuclear power in the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists. It's like, “Yep. Nuclear energy is still not the answer.” For some men, there is this idea that we’re going to nuke our way out of climate problems.

ORESKES: For some, nuclear power is the sort of holy grail. I think it's the kind of cargo cult. Nuclear power is this weird thing. Grown men get all giddy when they talk about nuclear power.

If you look at the evidence, this is a technology that has a 60-year history of overpromising and under producing. This was supposed to be the technology that gave us nuclear cars and electricity too cheap to meter. And not only did it not do that, it has been consistently more expensive, in most cases, way more expensive than the alternatives. It has been a colossal boondoggle, massively subsidized by the federal government.

DICHRON: That's the thing that strikes me. The nuclear energy people always come running to the American taxpayer to beg for more money.

ORESKES: Many of the people who promote nuclear power are the same people who will tell you that we should leave energy problems to the private sector. That’s an unbelievable contradiction. It has never been cost competitive. Physicists really hold out hope that nuclear will finally deliver on its promise after 60 years of failure.

In the case of nuclear power, because of real serious health and environmental concerns, you have spent huge amounts of money on safety precautions. These are real concerns, not just people being worry warts. This makes the technology intrinsically expensive. Even if the technology improves, nuclear power defies the standard model of technological development, which is that prices come down with better technology.

It's a very exceptional technology that way.

You would think that people who talk about evidence or facts would notice that very distinctive fact about nuclear power and say, “Wow, 60 years of experience and it's still just as expensive as ever. That's telling us something.”

DICHRON: Climate scientists seem loathe to speak up about the fossil fuel money that is being pumped into these energy and environment centers at universities. I've watched two of your students, Geoffrey Supran and Ben Franta tweet about it.

ORESKES: I know. They get a lot of heat.

DICHRON: They get a lot of heat, and ugliness. I’m thinking of tweets I’ve seen by a couple of women in climate science, whose names escape me now. They don’t seem to know what they’re talking about.

I kinda’ know a little bit about the influence of money, because I wrote a law on it, advised Members of Congress and foreign leaders on the issue, and have given lectures on money corrupting science at universities, including Harvard. And I see this tone-deaf response to reality—anger if you bring up fossil-fuel funding in climate science, before getting blocked on Twitter.

ORESKES: A lot of scientists are actually pretty naive about the political economy of science. And then they take it personally. They think that you're attacking their objectivity and their credibility.

But even so, the political economy of science needs to be addressed. Denying that doesn't help, because we want to maintain the credibility and integrity of science.

This is what my new book is about, how the funding influences the questions that get asked. Funding serves as a set of blinders. And it doesn't mean that the scientists who do the work are bad people or corrupt.

DICHRON: There was an article out about a year and a half ago or two years ago, and the theme was about some corruption in science because of “the long history of corporate funding.” I read it and I'm like, “This article's wrong.”

ORESKES: Yes.

DICHRON: And I look on Twitter and sure enough, all these science writers are applauding the article and retweeting it. The only two people I saw tweeting that the story was wrong, were you and Audra Wolfe, who is also an historian.

The corporate dominance of academic science actually started in our lifetimes. There was an inflection point in the late 60s, early 70s.

ORESKES: Yeah, a lot of journalists think history is what happened three weeks ago. This is why I live with a constant source of teeth gritting over the overgeneralization from whatever happens to be going on at this moment in time. Funding for science is a complicated thing, and it has changed more than once.

If you go back to the early 20th century, there wasn't much funding for science. And European science in the 19th century is mostly done by aristocratic people who are essentially independent scholars.

DICHRON: That’s Thomas Jefferson, a self-funded gentleman scientist.

ORESKES: But that begins to change in the late 19th century when governments become interested in science. You see the growth of things like geological surveys, weather service, Army Signal Corps. There’s always been some science in the military.

Then in the 20th century, it shifts again with the rise of corporate R&D. You get the development of big corporate laboratories, Dupont, Eastman Chemicals, associated with Kodak and the developing of film. There’s big growth of corporate science, but it's not corporate funded science of universities. And some of that science was really good. Irving Langmuir won the Nobel Prize in the 1930s for work he did at GE.

If someone accuses me of being anti-business, I point out that it’s not like corporate science is bad and academic science is good. It's a much more complicated story.

DICHRON: When people say something like that about me, I point out all the good that comes from corporate science. People are reading this interview on a computer made by a corporation, and the interview is brought to them with electricity made by a corporation.

ORESKES: Right. It’s not corporations that are the problem, it’s what they sometimes do. But then it shifts again with World War II, where there's military funding of science. And then it shifts again, after the war with the creation of National Science Foundation and the National Institutes of Health, and these federal agencies for funding academic research.

But then it gets shifted again in the last maybe 30, 40 years because of the reduction in the federal commitment to science funding, and the rise of corporate sponsorship of science inside universities. And that's the stuff that you know more about than I do, because that's played such a big role in biomedicine.

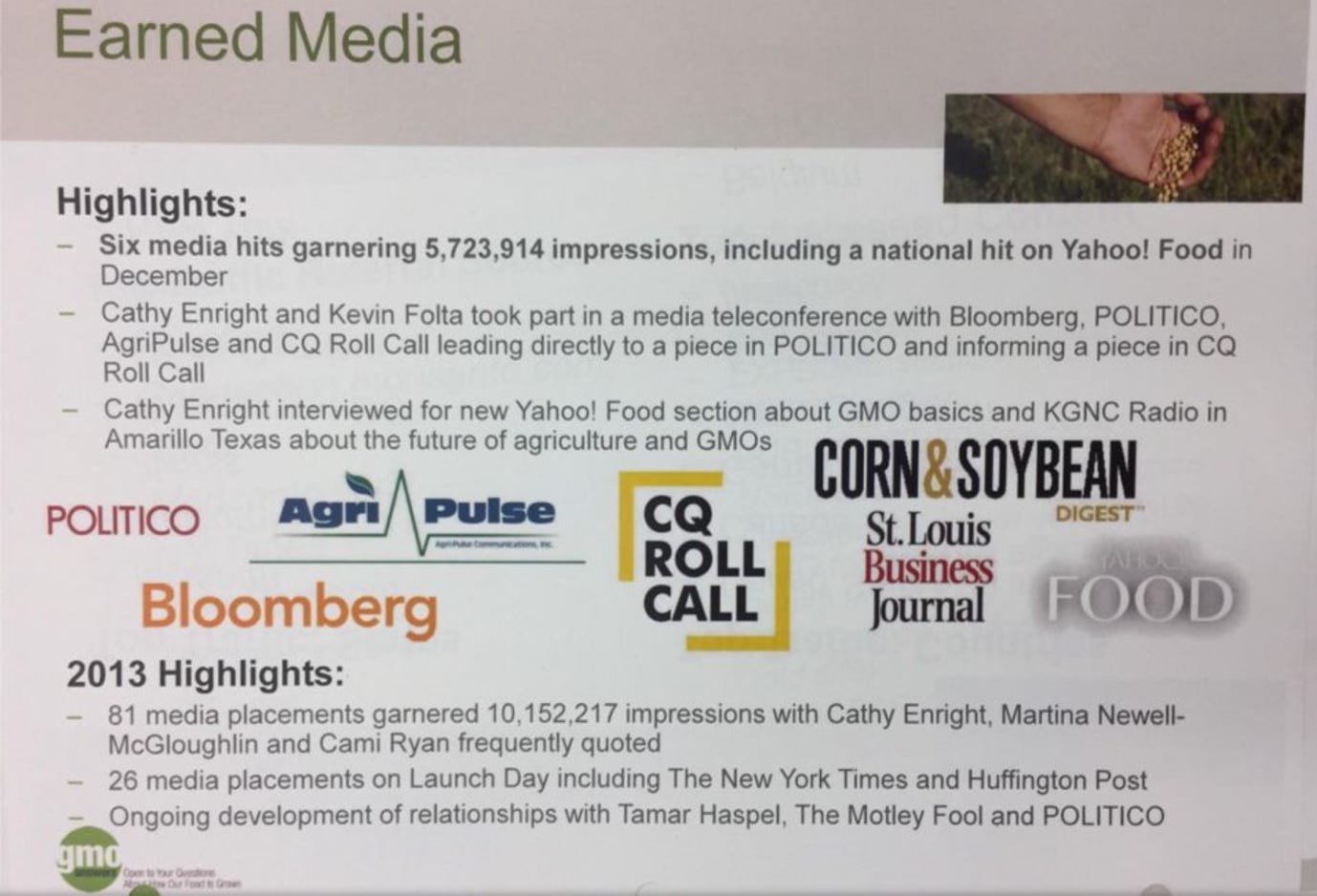

DICHRON: I interviewed you for a story about this panel at the National Press Club that was sponsored by Scientific American and GMO Answers, a group run by the PR firm Ketchum. That panel had Jim Hansen to talk about nuclear energy, and they had another woman there to talk about chemicals. And then they had someone else to talk about vaccines.

There was this was a subtext that there is a consensus that vaccines are safe; there's a consensus that global warming is happening; and there's a consensus that GMOs are safe. We are in this time where the term “consensus” is being seized upon. And I'm always like, “Whoa, what do you mean consensus?” I see consensus being used now as sort of a trick to say that, “If you believe in global warming, and you believe tobacco is bad, then you must believe in ‘X’ as well.”

ORESKES: You know as well as I do that the forces of disinformation will stop at nothing, and do many unprincipled and venal things. The deliberate misuse and misrepresentation of a term like “consensus” is one of many examples.

It's not meaningful to say, “Oh, there is a consensus.” In my 2004 paper on the fact that is consensus on climate change, I was absolutely explicit, “Most of the observed warming of the last 50 years is likely to have been due to the increase in greenhouse gas concentrations.”

DICHRON: On climate change, there's a consensus that it's happening; there's a consensus that humans are doing it. But beyond those couple of things, there's a whole lot of questions.

ORESKES: I haven't looked at this as closely as I looked at climate change. But I think it is true that among biomedical researchers, biology type people, there is a consensus that GMOs are probably safe to eat. But whether they're safe to eat, is just one of many different questions. And one of the things that industry tries to do, in a way that's quite nefarious, is to conflate all the different concerns about GMOs with the question of food safety. To imply that, if you don't like GMOs, you are scientifically illiterate because GMOs are safe to eat.

The counter example for this is the Pope. The Pope actually pays tremendous amount of attention to science. He's organized many scientific meetings at the Pontifical Academy of Sciences. He listens very closely to scientific advisors from the Pontifical Academy. And he doesn't like GMOs. And it has nothing to do with food safety.

DICHRON: Where do we kind of go to really understand what's going on? That's something I struggle with all the time. We know tobacco is bad, and that there is climate disinformation, but are we really equipping ourselves to understand the next thing? Or are we just muddling through it all?

ORESKES: I think we are muddling through, because that is basically what people do. Part of what I do is to illuminate patterns. If a person were to read “Merchants of Doubt” they would recognize the pattern when it crops up somewhere else.

I get emails all the time where someone is dealing with this in some other area, who wants to know if I can help, or asks if I have been looking at this specific example. And that's why it's helpful, so that you don't have to reinvent the wheel every single time.

This ends part three of “NAOMI ORESKES: DICHRON INTERVIEW.” To start at part one, click here.